A River Runs Through It

“The idea of wilderness needs no defense, it only needs defenders.” – Edward Abbey

Jim and Ted Baird are brothers, adventurers, videographers, and rugged wilderness enthusiasts. They gained significant notoriety by winning the fourth season of the History Channel’s hit series Alone, outlasting the other contestants, and capturing the show’s $500,000 prize. The pair spent a grueling 75 days in the remote Quatsino Territory on Vancouver Island, surviving with nothing more than the 10 tools they selected to bring with them, the skills they learned before appearing on the show, and their trust in each other as brothers. While their relationship can at times be humorously cantankerous, don’t doubt for a second that if you stepped up to one of them in a bar, you’d best be prepared to fight both.

Since winning Alone, the brothers have continued to document their adventures on YouTube. In an epic 24-part series titled “Beyond the Height-of-Land,” the Bairds chronicled their nearly 450-mile canoe trip up the remote Barrington River in Northern Manitoba, across a brutal portage over a height-of-land, and down the South Seal and Seal Rivers to the coast of the famous Hudson Bay. Along the way, they paddled across huge lakes, encountered a dizzying array of wildlife (a wolverine, a moose, countless seals, and a half dozen polar bears among them), enjoyed incredible fishing, navigated dangerous whitewater rapids with mixed success, and dealt with the unrelenting assault of hordes of summer bugs.

In Episode 19, the pair were near the end of their journey down the Seal when they happened upon a small cabin constructed by Environment Canada, a powerful arm of the Canadian federal government. This was the first sign of civilization the brothers had seen in weeks, and yet they were less than thrilled with the discovery. Jim pointed the camera at himself and explained why (emphasis added throughout, lightly edited for clarity):

“Basically, they use this to just collect stats and details on the flow of the Seal River. These are the kind of things they do just to get info on what resources are here and also what rivers they might decide to dam. They’ll test the flow and decide whether this would be a good place to build an enormous power dam and run endless, countless miles of blazes through the wilderness to get the hydro out of here – that we don’t even need – to God knows where.

Unfortunately, a lot of our wild rivers have succumbed to massive-scale hydroelectrical development. I don’t think that’s going to happen to the Seal because it is a Canadian Heritage River right now, and it’s obviously incredibly special and [Environment Canada] recognizes that. But, um, yeah. They don’t put these hydro stations here just to help canoeists look up what the flow levels are.”

Those less familiar with Canadian culture might have missed important clues in Baird’s statement that reveal the extent to which hydropower dams dot much of the country’s otherwise spectacular landscape. In using the phrase “get the hydro out of here,” Baird was referring to electricity, but in much of Canada the words “hydro” and “electricity” are practically synonymous. One’s “electricity bill” is commonly referred to as a “hydro bill,” and a child might be instructed by their parents to turn off a light switch to “save on hydro.”

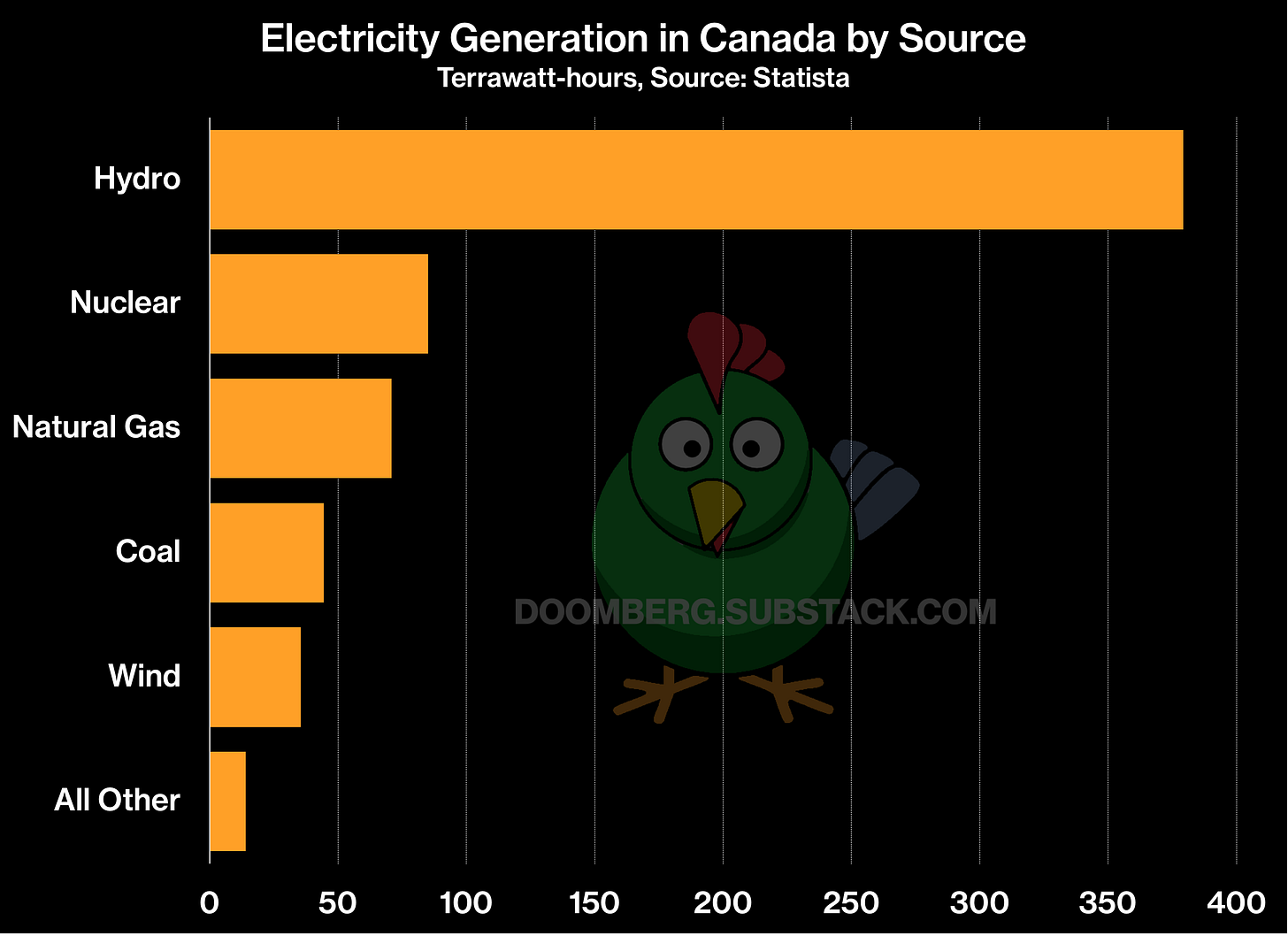

This cultural nuance makes sense when you consider that hydropower provides 60% of Canada’s electricity, compared to just 6% in the US. The province of Québec gets more than 95% of its electricity from hydropower and is a major exporter of power to the US Northeast. New York City recently signed a contract to obtain 20% of its future electricity needs from Hydro-Québec.

As one might imagine, damming Canadian rivers to supply electricity to Americans is a controversial subject in the Great White North, a sentiment that finds its way into Baird’s use of the phrases “that we don’t even need” and “to God knows where.” He knows where, but to notoriously polite Canadians, some things are best left unsaid, even words that protest the relegation of one’s country as a mere energy vassal to the world’s dominant suzerain.

The debate over hydropower in Canada crystalizes the undeniable fact of trade-offs in all decisions about energy. While hydropower is commonly understood as “renewable” and “green” (and therefore “good”), the full picture is decidedly more complicated. As the West attempts to reengineer society around minimizing carbon emissions, what role can, should, and will hydropower likely play in the coming decades? Let’s dig in.