Alberta Clipper

A storm is brewing in the energy-rich Canadian province.

“Canada is like a loft apartment over a really great party.” – Robin Williams

The first written record of what would eventually be known as the Canadian oil sands dates back to 1715 when an employee of the Hudson’s Bay Company noted that local indigenous people would boil the material to extract bitumen for waterproofing their canoes. By the 1930s, enterprising experimentalists discovered that oil sands could be used to produce a substance suitable for use in road paving applications, further increasing interest in the massive natural deposits found in the westernmost reaches of modern-day Canada. Decades of further study would lead to the characterization and commercial development of the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin (WCSB), one of the world’s largest and most important hydrocarbon resources.

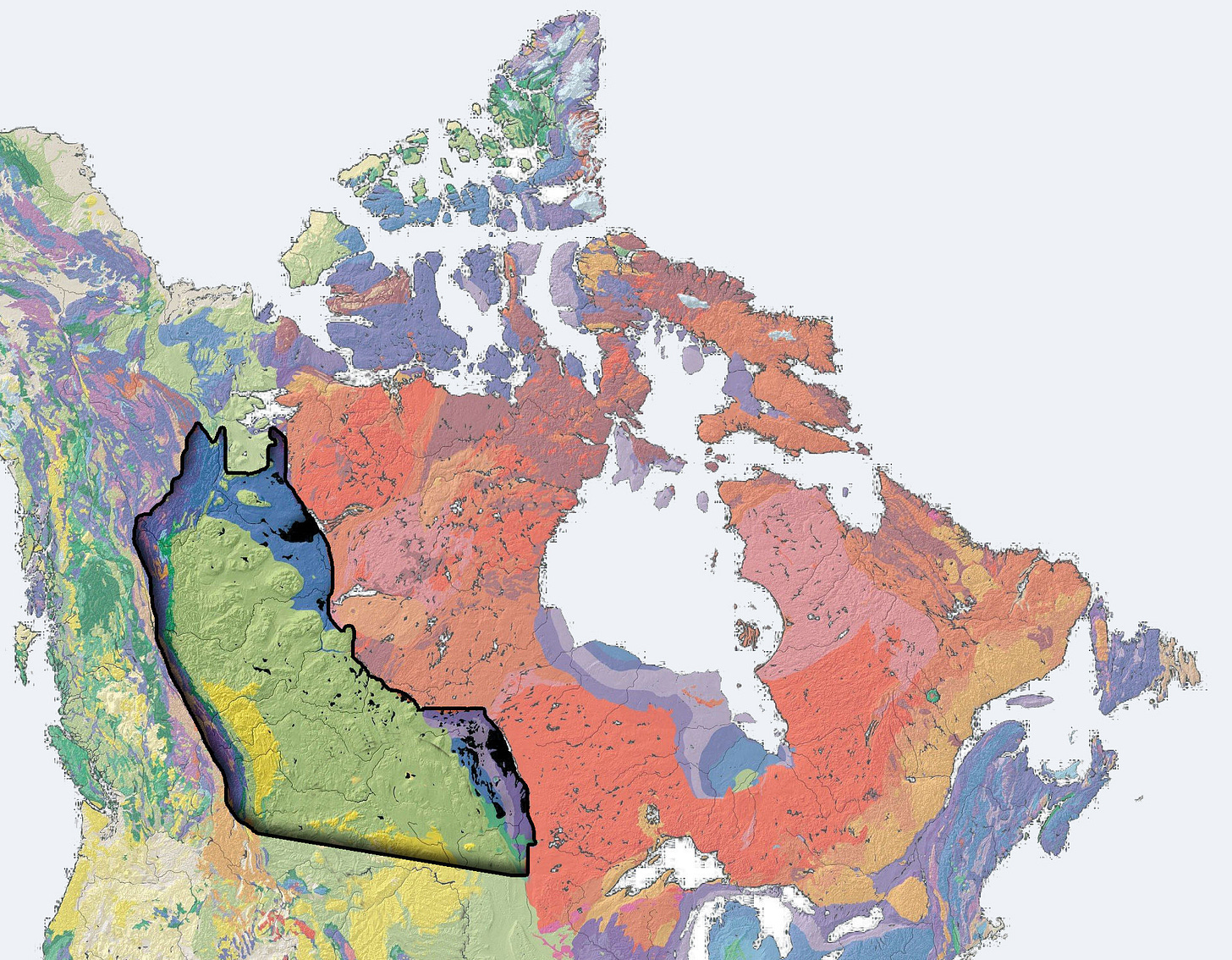

Spanning an area of approximately 540,000 miles, the WCSB stretches from southwestern Manitoba to northeastern British Columbia and the southern Northwest Territories, covering more than half of Saskatchewan and virtually all of Alberta in between. Estimated to contain 1.8 trillion barrels of oil—of which 165 billion barrels are recoverable using today’s technology—and hundreds of trillions of cubic feet of natural gas, the WCSB ranks among the largest hydrocarbon resources in the world. At current production levels, the region contains enough economically viable energy to last well more than a century. Even under conservative assumptions of continued technological advances, the amount of energy that can eventually be extracted from the WCSB is practically limitless.

As with most globally significant resource discoveries, the development of Canada’s oil sands has not been without significant controversy, a situation exacerbated by unique aspects of the country’s history. For example, Canada’s map is still very much a work in progress. The Province of Newfoundland didn’t officially join Canada until 1949, and it was renamed the Province of Newfoundland and Labrador in 2001. In 1999, the territory of Nunavut was created from the eastern portion of the Northwest Territories, providing greater self-governance for the Inuit people of the Eastern Arctic.

Beyond the evolving nature of Canada’s cartography, there is also the vexing question of power-sharing arrangements between and among the territories, provinces, Aboriginal peoples, the Canadian federal government, and the British monarchy itself. Canada didn’t formally repatriate its constitution until 1982, and the French-speaking Province of Quebec has never officially signed on to the document. There is also the complex issue of Canada’s system of equalization payments, which we have previously described as “a constitutionally mandated program meant to address economic inequalities across provinces by redistributing federal revenues to those below the country’s average fiscal capacity.” In essence, the energy-rich western provinces financially support those to the east, an arrangement with a popularity that follows the money.

Against this backdrop of sovereign metastability, we have been monitoring the situation developing in Alberta with significant interest:

“Alberta Premier Danielle Smith plans to challenge the proposed federal greenhouse gas emissions cap using the Alberta Sovereignty within the United Canada Act. The government intends to take legal action if the cap becomes law and aims to assert provincial authority over emissions data and restrict federal access to oil and gas facilities.

Smith, as reported by the Canadian Press, said: ‘We have been very clear that we will use all means at our disposal to fight back against federal policies that hurt Alberta, and that is exactly what we are doing.’”

The essence of this dispute arises from Canada’s hapless and wildly unpopular prime minister, Justin Trudeau, and his obsession with being seen as caring about carbon emissions. The proposed federal law in question would force Alberta to significantly reduce oil and gas production to meet the proposed CO2 targets. Trudeau’s point person on the initiative is former Greenpeace activist and current Minister of Environment and Climate Change Steven Guilbeault, a deeply controversial figure not known for his grasp of physics or industry. In other words, the stage is set for a titanic clash of ideologies, with ramifications that spread well beyond Canada’s borders.

Will Canada become the next country to impale its interests at the altar of the Church of Carbon™ or will the Battle of Alberta be yet another crushing blow to the global climate agenda? With an important election on the horizon, we’ve put together a viewing guide for those watching from afar. Let’s dive in.