Atlas Won’t Shrug

The human endeavor demands ever more energy. So it shall be.

“The crisis of today is the joke of tomorrow.” – H.G. Wells

On August 15, 1971, President Richard Nixon closed the gold window, setting off 50 years of relentless debasement of the US dollar. In 1973, war broke out in the Middle East, triggering the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) to place an unprecedented embargo on oil exports to the West. The Shah of Iran was overthrown in 1979, an event that eventually led to war raging between Iran and Iraq during most of the 1980s. On August 2, 1990, Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait. By January of the next year, the US military led a coalition force of over one million soldiers into battle, ejecting the Iraqi army from its neighbor in a matter of weeks. The late 1990s saw a series of financial crises strike the global economic system, including the Asian currency crisis of 1997, the Russian Ruble default in August of 1998, and the collapse of Long-Term Capital Management a month later.

The turn of a new century brought with it a continuation of this parade of catastrophes. The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, triggered a recession, a major war in Afghanistan, a second go at Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, and a perpetual “war on terror” that has destabilized Libya, Syria, and several other regimes the world over. The global financial crisis of 2007-2009 nearly brought the world’s economy to its knees and several iconic financial institutions collapsed. In the mid-2010s, Venezuela—a founding member of OPEC and major oil exporter to the US—crumpled into a hyperinflationary tailspin. In 2015, Canada elected Justin Trudeau as Prime Minister and reelected him in 2019. The world descended into the depths of the Covid crisis in early 2020, Russia invaded Ukraine in February of 2022, and yet another war broke out in the Middle East in October of 2023, a conflict that risks creating a direct kinetic confrontation between the US and Iran.

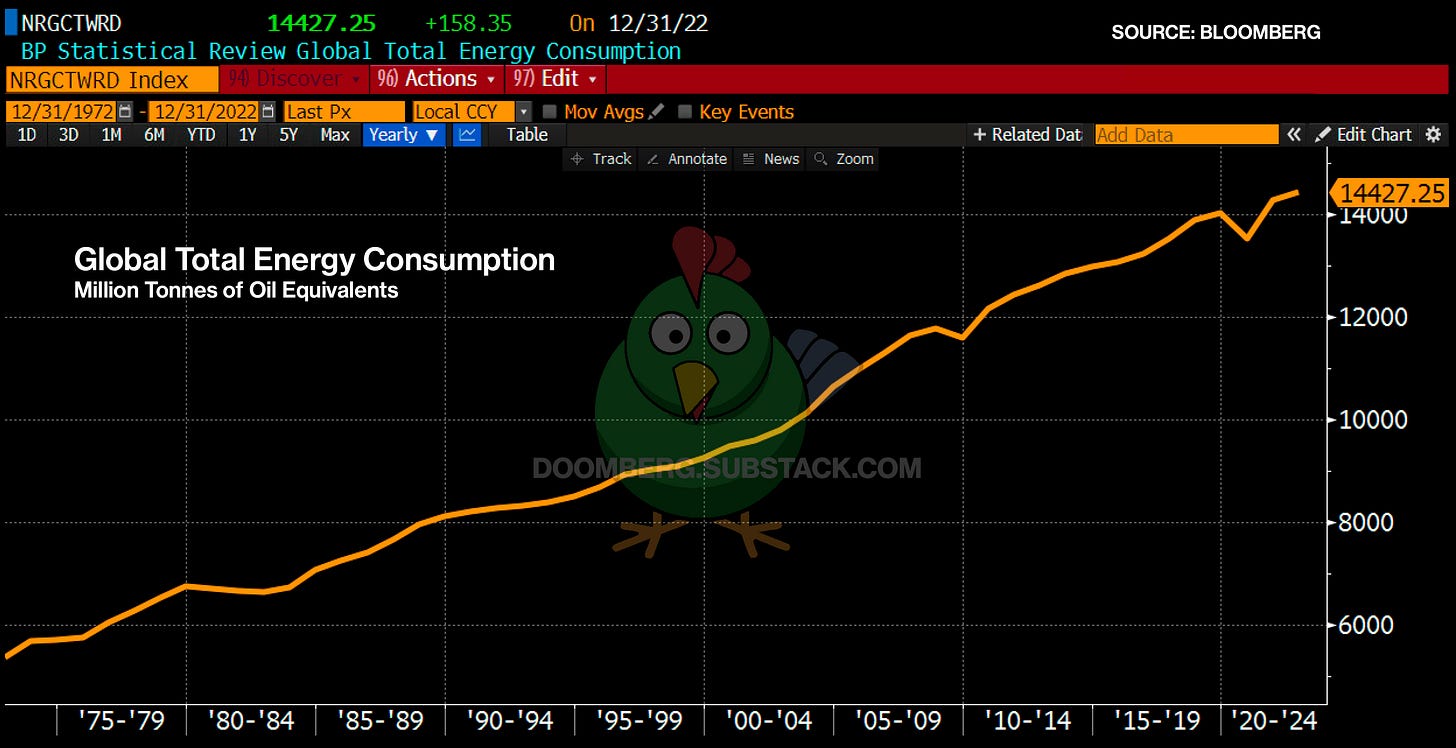

How did the world’s appetite for primary energy react to all of these events? It mostly ignored them, grinding higher in an upward-sloping, gently oscillating sine wave:

What nearly all market observers get wrong is the nature of the relationship between energy and the economy. Most view energy as an input into economic activity, as though its contribution to gross domestic product (GDP) is no different than the other measurable goods and services that go into that important calculation. This is how otherwise intelligent people observe Russia’s comparatively modest GDP and conclude that it is nothing more than “a gas station masquerading as a country.” Such arrogance is the root cause of the West’s catastrophically flawed sanctions policy against the country, and such ignorance explains the dangerously naïve calls to “end fossil fuels,” the equivalent of demanding suicide on a billion-person scale.

This is a concept so vital that it is worth writing with bolded emphasis:

Energy is not an input into the economy, IT IS THE ECONOMY. Humanity organizes its economic activities to ensure a steady growth in the extraction and exploitation of primary energy because energy is life, standards of living are defined by how much energy is available to be exploited, and all humans everywhere are perpetually seeking a higher standard of living.

As far as foundational axioms go, that’s a pretty good one.

One category of people that fails to understand this concept (and should know better) includes those who cling to the thesis that humanity will soon be confronted with peak cheap oil, and that once this event unfolds, oil prices will remain stubbornly, catastrophically high, and life as we all enjoy it today will suffer. This cohort gets the first half of the scenario mostly right—a sudden and meaningful loss of access to economically accessible oil would indeed be a crisis. But what they get wrong is just how temporary that crisis would be, the extent to which entire economic and political systems would swiftly reorient, and the ruthless efficiency with which humanity would regress up to that gently oscillating sine wave of primary energy consumption.

Over the past several weeks, we have systematically chronicled why we believe peak cheap oil is a myth, the variety of options available in the unlikely event that worst-case scenarios actually materialize, and summarized our overall views on the topic in our January Doom Zoom for Pro Tier subscribers. After consuming various critiques of our work, we find ourselves underwhelmed by the arguments meant to negate our hypothesis, and more confident than ever in the validity of our initial assertions. Let’s explore why.