Chasing an Energy Moonshot

“There are no passengers on spaceship Earth. We are all crew.” – Marshall McLuhan

On August 2, 1939, Albert Einstein wrote a two-page letter that would alter the course of history. Addressed to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Einstein explained that physicists were close to unlocking the potential of nuclear energy and postulated that this new technology could be harnessed to create devastating weapons of war. He also warned that Germany was already pursuing such weapons, and encouraged Roosevelt that the US should do the same. Although Roosevelt’s initial response to the letter was tepid, key influencers around the President soon convinced him that this was a winner-takes-all race that the US was losing. What followed was the largest mobilization of talent and resources for a single scientific project in history.

The inside story of the Manhattan Project is chronicled in Richard Rhodes’ gripping book The Making of the Atomic Bomb. In reading it, one can’t help but marvel at the power of nuclear energy, the brilliance of the scientists involved, the incredible logistical challenges that were overcome, and the tragedy that humankind has not fully capitalized on the obvious potential of the resulting technical breakthroughs. Instead, we are perpetually a button push away from human extinction because we harnessed this technology to develop weapons of mass destruction. The rational fear of such weapons undoubtedly fuels our stubborn resistance to tapping the nearly limitless supply of cheap and carbon-free energy that nuclear technology can provide.

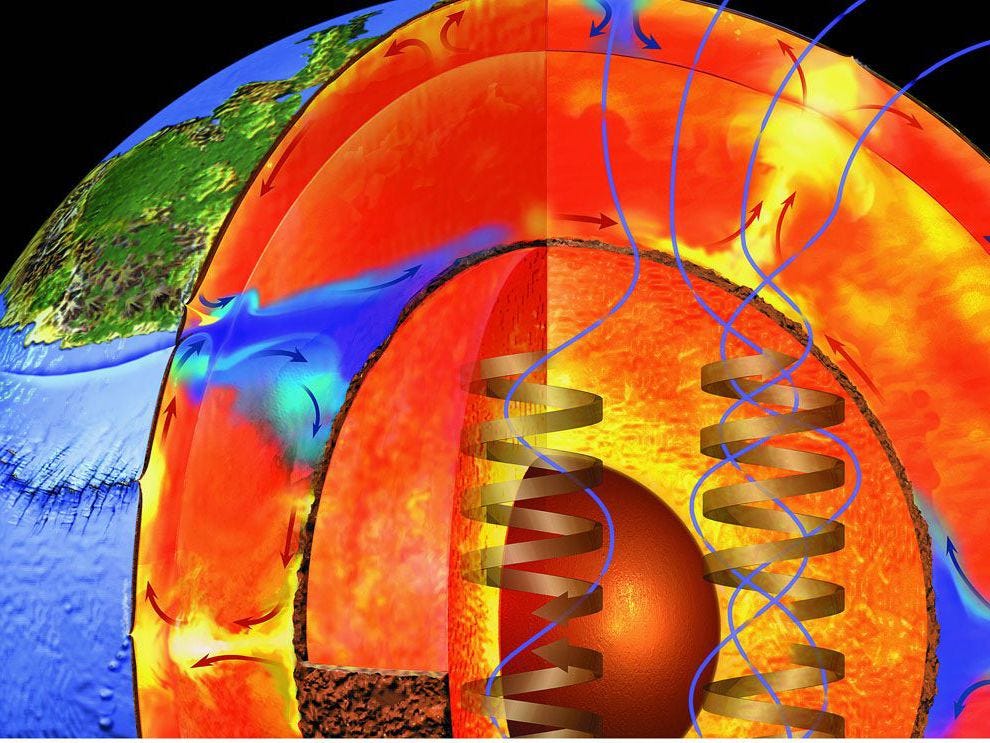

Although most people understand that nuclear reactions power the sun, it is less well known that Earth itself is a giant nuclear reactor. Nuclear fission powers the movement of Earth's continents and crust, and the temperature of Earth’s core is estimated to be 5,200° Celsius. Here’s a summary from National Geographic (emphasis added throughout):

“Earth’s core is the furnace of the geothermal gradient. The geothermal gradient measures the increase of heat and pressure in Earth’s interior. The geothermal gradient is about 25° Celsius per kilometer of depth (1° Fahrenheit per 70 feet). The primary contributors to heat in the core are the decay of radioactive elements, leftover heat from planetary formation, and heat released as the liquid outer core solidifies near its boundary with the inner core.”

Where significant temperate gradients exist, so too does the possibility of creating electricity. Power plants that use uranium, natural gas, coal, or oil purposely create extreme temperature gradients within their reactors, which are then used to boil water. The resulting high-pressure steam is used to spin turbines, and the mechanical energy from such turbines is converted to electricity using generators. To a first approximation, the backend of all these power plants is substantially similar. Once steam is generated, the path to our light switches is a comparatively simple problem.