Cold Truths

Physics, storytelling, and forgetting hard-fought wisdom.

“Nature never deceives us; it is we who deceive ourselves.” – Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jack London’s 1908 classic short story “To Build a Fire” follows an unnamed man and his dog as they hike through the Yukon wilderness on an extraordinarily cold winter day. Drawn to the area by the allure of the Klondike Gold Rush, the protagonist is more cocksure than experienced and has foolishly ignored an elder’s advice to never travel alone in such brutal conditions. When his spit freezes and shatters in the air before hitting the snow-covered ground, he finally begins to realize what his canine companion already knows by instinct: this was probably a mistake, and is unlikely to end well.

London’s increasingly tense description of the man’s run of bad luck will ring familiar to those who have experienced a cascading set of inconveniences that devolve into a full-blown crisis. It is small wonder that Ruby Love’s haunting rendition of the story has quickly become one of the most popular pieces on our sister publication, Classics Read Aloud, since its September launch. Listen for yourself here—it will be 40 minutes extremely well spent.

Stripped to its essence, London’s iconic tale is a thinly veiled physics lesson. Core to its curriculum is the concept of “thermal comfort”—the notion that human life can persist only within a surprisingly narrow window of temperature and humidity. The human body is little more than a symphony of complex chemical reactions whose sensitivity to those two parameters is frighteningly acute. The equilibria within each of us are so delicate that body-temperature fluctuations of just a few degrees can be fatal.

It is broadly accepted that humans maintain thermal comfort when the ambient temperature is between 67°F and 82°F and the humidity is between 30% and 60%. It should come as no surprise that the developed world invests a staggering amount of energy in heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) to create such favorable settings. The US Department of Energy estimates that 40 percent of the country’s carbon emissions can be traced to thermal comfort needs, accounting for significantly more energy than the transportation sector.

The ease with which you achieve thermal comfort is a reasonable proxy for your standard of living. If you glide daily from your warm home to your heated garage, where your modern, climate-controlled vehicle waits to transport you to a posh office, you are probably doing pretty well for yourself. If gathering firewood, boiling water over an open flame, and foraging for food in the wilderness are part of your daily chores, not so much. The difference between these two extremes is determined by how much primary energy is available to be harvested, but few in the modern world conceive of it that way.

This physics-first analysis explains at least one reason why efforts to fight global warming are doomed to fail. The global average surface temperature of the Earth—a number which, to us, seems rather difficult to measure—is widely accepted to be approximately 59°F, or 8°F below the lower bound of human thermal comfort. All things being equal, a bit of global warming is accretive to the human endeavor, as it closes the energy gap needed to achieve and maintain a reasonable lifestyle. Alarmists will undoubtedly be alarmed by this admittedly simplistic analysis, but we do not make the laws of physics—we merely recognize their omnipotence.

Thermal comfort also helps explain why the proposed elixirs to global warming—photovoltaic solar panels and giant wind turbines—are woefully inadequate. Both technologies have a way of going dormant just when they are needed most: in the dead of winter. As London’s tale makes so visceral, the need to achieve a stable environment for the body is an always thing, not an average thing, because it doesn’t take long for a substantial deviation from ideal to result in death. As our engineering friends would say, it only takes one zero in a geometric mean to know what the answer is.

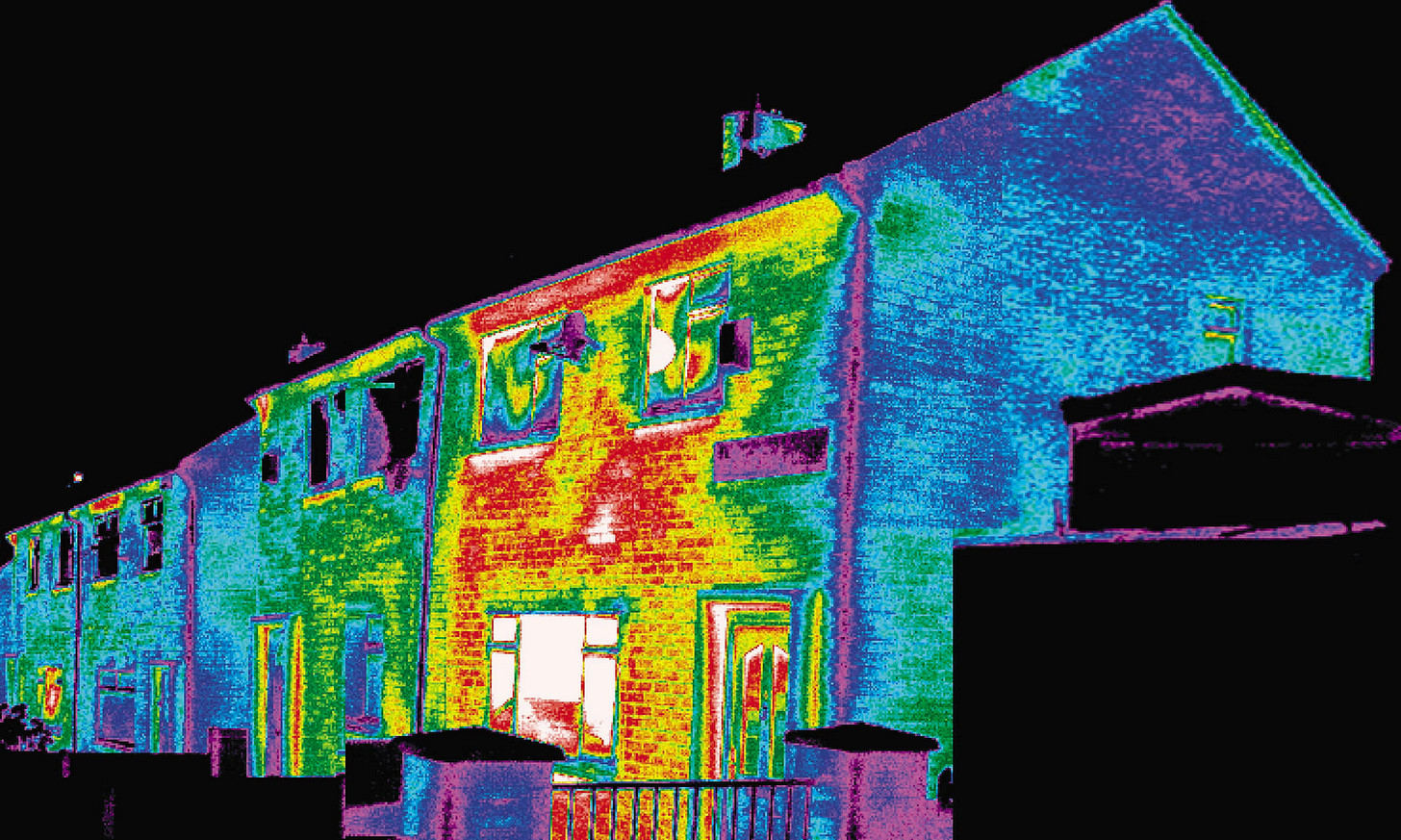

Consider the plight of the average citizen of the United Kingdom, a country that has embraced climate dogma like few others. Not only do the British pay more for less energy, but the average British home is among the oldest and least efficient in Europe. A sobering report in The Guardian last year captures the details:

“A total of 34% of UK households or 9.6m are living in cold, poorly insulated homes, according to analysis of the English Housing Survey by the Institute of Health Equity and Friends of the Earth. These 9.6m households also have an income below the Joseph Rowntree Foundation’s minimum standard for a decent living, meaning it is unlikely they would be able to afford the costs of adding insulation to their homes.

The report defines poorly insulated homes as those with an Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) rating of below C, which are unlikely to have double-glazed windows, energy-efficient lighting, draught proof doors and windows, or an efficient heating system.”

There is a direct, causal relationship between the ever-increasing difficulty of achieving thermal comfort in Britain and the unpopularity of its current ruling class, currently embodied by the much-maligned and politically tone-deaf Sir Keir Starmer.

This analysis at the individual and dwelling levels also integrates up to society as a whole, where it quickly becomes clear why the pursuit of developable energy resources is a core strategic imperative for nation-states. Countries blessed with abundant energy assets and the technical capacity to both extract them and defend them from invasion tend to flourish, while those lacking either are easily conquered or gradually fade from prominence. Every war ever fought was, at its core, an energy war—whether the participants realized it or not.

Take the ongoing conflict in Ukraine. While most of the global headlines late last week focused on Russia’s second use of its powerful Oreshnik intermediate-range ballistic missile against a defense-industrial facility in Lviv, our attention was directed to a massive missile and drone attack against key power plants in Kyiv on the same evening. According to open-source intelligence, both the CHP-5 and CHP-6 power plants—two critically important combined heat and power facilities that support the capital city’s residential water-heating systems—sustained massive damage.

Coming just ahead of the coldest week of winter, there can be little doubt that the intent of the attack was to inflict maximum suffering on the local population—a clear violation of international law. Not that anybody cares much about that anymore.

As vulgar as these attacks are, the sober facts of physics also dictate what little Britain—and Europe more broadly—can do about them. As we have long documented, Russia is an energy superpower, while Britain and the European Union are flaccid energy vassals. For all the propaganda permeating Western media outlets about the need to face the Russian war machine head-on, it simply can’t happen until massive changes in energy policy are implemented. That seems as remote a possibility as inflicting a strategic defeat on Russia anytime soon.

As Western nations have grown richer, the distance between the foundation of that wealth and the political leaders charged with shepherding it has only grown. The situation seems unsustainable, and something will soon have to give.

Storytelling plays a central role in human cultures because it helps shape how communities understand the natural world and their fragile place in it. The best stories capture collective memory, values, and identity across generations, and physics is a far more common—if unacknowledged—character than most realize. Be it the unnamed man in the Klondike, the beleaguered citizens of Britain, or innocent victims of war in Kyiv, the central lessons of “To Build a Fire” could not be more clear:

Energy is life, and the lack of it is death, be it individually, economically, or militarily.

“♡ Like” this piece and try not to freeze!

Excellent! This echoes Secretary Wright's persuasive writing while he was CEO of Liberty, Saving Human Lives. That is the bottom line: oil/gas save human lives. Having spent 50 plus years in environmental policy, I know my body's temperature comfort zone. Several years in Africa and Nepal/India cooking over wood and dung stoves taught me importance of prime energy for body comfort. Environmental/climate zealots start their advocacy from a baseline of energy comfort without contributing an iota to that baseline. You do not have to venture to the Yukon to come face to face with these realities, as the fragility of our grid makes clear year to year. The fatuous promotions of climatistas is indeed depressing, a road to a cold nowhere.

"Nuclear Power Could Heat Your Home" is my WSJ article about heating cities such as New York with leftover heat from nuclear power plants. A HEAT and power nuke in every city's backyard could get votes. https://www.wsj.com/opinion/nuclear-power-could-heat-your-home-cogeneration-district-heating-energy-steam-china-ap1000-11657734413?st=J1wjJM&reflink=desktopwebshare_permalink