Compressed for Time

In a pinch, virtually everything could be run on natural gas.

“Abundance is not something we acquire. It is something we tune into.” – Wayne Dyer

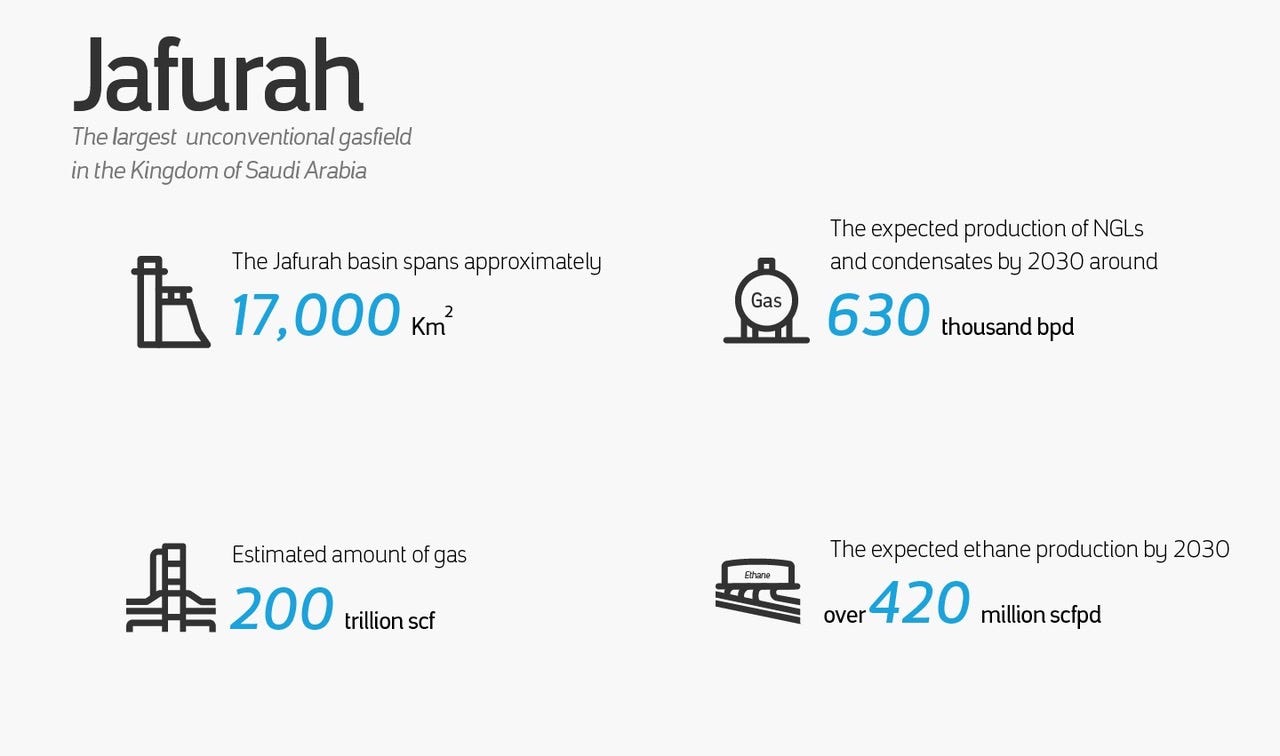

In the desert of Eastern Saudi Arabia sits what many believe to be the world’s largest shale gas field outside of the US. Endowed with an estimated 200 trillion cubic feet of wet gas, the Al-Jafurah field “is one of the most ambitious projects in [Saudi] Aramco's history.” Over the coming years, the Saudis plan to invest more than $100 billion to bring Jafurah’s huge energy resources to market as part of the country’s overall objective to increase its natural gas production by more than 50% by 2030. Once fully operational, Aramco expects Jafurah to produce 2.2 billion cubic feet per day (bcf/d) of natural gas, 630,000 barrels per day of natural gas liquids (NGLs) and condensates, as well as 0.42 bcf/d of ethane. It is anticipated that such production levels will be maintained for several decades, and the potential for further investment has not been ruled out.

The economic viability of Jafurah is a direct result of the industry’s relentless pursuit of technological development—that which was deemed “expensive or impossible a few years ago routinely becomes commonplace over time, converting ever-increasing swaths of resources into economically exploitable reserves.” In this regard, Jafurah is an expression of the formidable technical prowess of Saudi Aramco, brought to the fore in the company’s description of the enabling science behind the project (emphasis added throughout):

“This included the acquisition of comprehensive sub-surface data and the creation of geological maps to guide our explorations, and the drilling of appraisal wells — which were in operation for periods of up to three years — to assess productivity and improve our decision-making.

To take performance to the next level, we developed fit-for-purpose drilling solutions and implemented high-performance technologies. These included new designs of drilling systems, and a fleet of 'walking rigs' that can be moved as a complete unit from one well to another — improving both safety and operational efficiency.

And we applied innovative in-house technologies and best-in-class practices in hydraulic fracturing operations, that have already resulted in enhanced production and improved well delivery.”

Compared to its vast potential, Saudi Arabia has long been a laggard in the production of natural gas, accounting for just 3% of global supply in 2022. With so much cheap and easy oil to be had, the methane molecule was long considered something of a nuisance to the country’s energy ambitions. Even without Saudi Arabia’s full engagement, the world has been growing natural gas production at an incredibly consistent rate of 2.5% per year for decades, nearly doubling global supply since 1998. As natural gas becomes increasingly valuable and the world finds more uses for the light hydrocarbon liquids that are often associated with it, there is every expectation that this trend can continue for quite some time.

A key driver of Aramco’s recent gas initiatives is to free up oil for sale in the global markets—according to a recent report by the US Energy Information Administration (EIA), the country still relies on burning oil to produce one-third of its electricity. We return to the official Jafurah project website for more details:

“When Aramco's unconventional gas program reaches peak production, it is expected to generate energy for domestic consumption equivalent to displacing around 500,000 barrels of crude oil [per day], allowing this oil, and other petroleum liquids, to instead be utilized to create a range of valuable products, including ones for use in our own chemicals business.”

In “Putting a Ceiling on the Equilibrium Price of Oil,” we showed how chemists are able to transform natural gas into molecular drop-in replacements for refined products like diesel and jet fuel at commercial scale. We proposed that the ability to do this effectively puts a ceiling on the equilibrium price of oil and serves as an insurance policy against meaningful shortages. As the Saudi’s Jafurah project demonstrates, with modest expenditures by end users—like making the necessary investments to be able to burn natural gas instead of oil at an electricity generation plant, for example—natural gas can be a meaningful direct substitute for oil as well, circumventing the need to undergo chemical transformation before being burned.

Scanning the full range of current use cases for refined products of oil, we find countless examples where simple modifications could theoretically allow for a direct switch to natural gas as a primary fuel. In most instances, the technology already exists. In a pinch, most of modern society could be run on natural gas alone, assuming an adequate supply of the stuff. If peak cheap oil were to truly manifest, the negative consequences of such a development would surely be blunted by substitution across these options. Let’s explore a few hypotheticals.