Crouching Tiger, Hidden Problems

“A value is valuable when the value of value is valuable to oneself.” – Dayananda Saraswati

What is something worth? For many, this is a simple question with an easy answer: whatever somebody is willing to pay for it. In practice, valuation is critically important to the core functioning of finance over the long run. How value is determined – and who gets to do the determining – can make the difference between fortunes won and lost. As with all such circumstances, if there is big money on the line, there will be people with the means, opportunity, and motive to stretch the boundaries and grab more than their fair share of it.

In the public stock markets, valuation seems straightforward. Stocks trade hands between willing buyers and sellers during market hours, and when the markets close there’s a final trading price for the day. But things aren’t always so transparent. Imagine you are a money manager with a large position in XYZ stock. It is somewhat illiquid in that it doesn’t trade in big volumes. Since your compensation depends in part on the closing value of XYZ on December 31st, you decide to make a series of small buys in the last few minutes into the close, artificially pushing the value of XYZ up by 5%. Your entire stake now gets marked there, but it isn’t real - you have merely “painted the tape.” This brilliant meme from @Keubiko captures the essence of the issue well:

Now, there are rules against such manipulations in the public markets, but what if XYZ Company is a privately-held startup?

If a founder sells 15% of her startup to an accredited investor in exchange for an injection of $150,000, then it might be fair to say her company is worth $1 million. What if it is the founder’s parents making the investment? A best friend? A business partner in a different but related venture? Throw into the mix critical deal terms like distribution preferences, board seats, voting rights, anti-dilution protections, and other negotiated concessions, and it quickly becomes apparent how difficult the concept of private value can become – and how easily it can be manipulated.

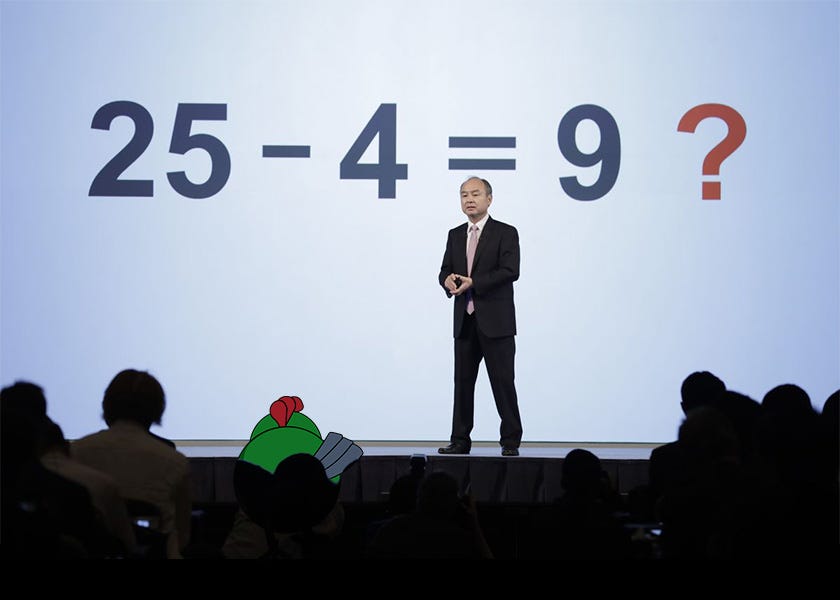

Things get really interesting when the public and private company worlds collide, and no person has pushed the envelope harder at this interface than Masayoshi (Masa) Son, Chief Executive Officer of SoftBank. SoftBank is a large Japanese conglomerate consisting of run-of-the-mill operating companies and a staggering array of aggressive private investments deployed through all manner of complex structures, often with significant leverage. Known as a swashbuckling gambler with an incredible tolerance for volatility, Masa Son is famous for his bizarre investor presentations during which he rails against the value the public markets assign to the whole of SoftBank, especially compared to what he believes is its proper sum-of-the-parts valuation. Below is a famous moment from his 2020 presentation, delivered at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, during which Masa Son claimed SoftBank’s equity was worth 25 trillion Yen, yet the market was assigning it only 9 trillion Yen (on the slide, he’s backing out the 4 trillion Yen in SoftBank debt).

Perhaps the absurd story of the Masa-backed Indian startup OYO Rooms (OYO) might explain some of the market’s skepticism.

We’ve long been fascinated with OYO and its young founder, Ritesh Agarwal. You can think of OYO as the WeWork of budget hotel rooms in Southeast Asia. The business model involves signing participating hotel chains onto their app, promising them a fixed revenue stream, paying to upgrade their rooms to a common OYO standard, and managing the risk of filling those rooms with satisfied customers. We’ve never understood how this enterprise was going to sustainably make money, but with SoftBank the force behind WeWork, it’s not surprising that Masa Son was seduced by Agarwal’s concept as well.

In July of 2019, we were treated to a fascinating set of headlines about an OYO transaction that – to put it mildly – seemed to bury the lede. Here’s how things were initially described by CrunchBase (emphasis added throughout):

“The fast-growing Indian hospitality business Oyo has garnered a valuation of $10 billion after its founder, Ritesh Agarwal, purchased $2 billion in shares from venture capital firms Sequoia Capital and Lightspeed Venture Partners, the company announced Friday.

Agarwal, 25, founded Oyo in 2013 at the age of 19. Following immense growth of the now global hotel chain business, Agarwal opted to increase his 10% stake to 30% via a Cayman Islands company called RA Hospitality Holdings, according to The Wall Street Journal. SoftBank has also increased its percent ownership as part of this round, now owning nearly half of the company.”

To the casual observer, this would seem like an incredibly bullish development. The company is now worth $10 billion! The OYO CEO was so confident in his company’s prospects that he personally bought $2 billion worth of stock! What’s not to like? This mark made OYO among the most valuable investments in SoftBank’s portfolio at that time. When we first read this announcement, we wondered why the bluest of blue-chip VC firms, Sequoia and Lightspeed, were bailing on a huge chunk of their investment in such a hot startup, and how a founder in his early 20s without a major exit under his belt could get his hands on $2 billion in cash? As it turns out, Agarwal borrowed the money, leveraging a personal guarantee from Masa Son himself to buy the shares at the new, elevated valuation:

“In a highly unusual move, Agarwal, now 26, borrowed $2 billion to buy shares in his own company as the valuation rose, and Son personally guaranteed the loans from financial institutions, including Mizuho Financial Group Inc.”

Highly unusual, indeed.

According to (paywalled) data from CrunchBase, SoftBank led OYO’s $100 million Series B round in July 2015 and its $90 million Series C round in August 2016. SoftBank Vision Fund then led OYO’s $250 million Series D round in September 2017 and its $650 million Series E round in September 2018. Presumably, all these injections funded cash-burning growth and came at progressively higher valuations.

With the July 2019 transaction, the CEO of SoftBank painted the tape by effectively lending money to the CEO of a startup that he and his affiliated entities had already gone all-in on. The headline became the higher valuation. How Agarwal funded his increased stake and the fact that Sequoia and Lightspeed had liquidated much of their OYO stock became afterthoughts. SoftBank promptly marked its various investments in OYO at the new $10 billion “valuation,” which is no minor thing since Masa Son is known to pledge substantial portions of his personal holdings in SoftBank stock for loans to fund his lifestyle and other investments.

In this seemingly endless loop of conflicting motivations and circular finance, was OYO really worth $10 billion in July of 2019? Does 25 – 4 = 9? make more sense now? Nearly three years later, presumably with the depths of the Covid-19 crisis behind it, OYO is still a serious cash burner and seems to be struggling to generate enthusiasm for its planned initial public offering (IPO). Here’s how Bloomberg recently described the situation:

“Oyo, the high-profile affordable lodging startup that filed for an initial public offering last year, is considering slashing its fundraising target by half or even shelving the debut, according to people familiar with the matter.

Faced with headwinds including slumping stock markets, Oyo-operator Oravel Stays Ltd. could clip its Indian IPO from the nearly $1 billion initially sought to half that, the people said, declining to be identified discussing internal matters. It’s considering also halving its expected valuation from the $12 billion originally targeted, they said. Oyo could even decide to suspend its IPO plans, the people said.”

By our math, half of 12 is 6, which is decidedly less than 10, and we suspect this IPO will get shelved lest a new and unfavorable “valuation” force SoftBank to write down its investments. With Chinese internet stocks crashing and US growth stocks swooning under the pressure of increased interest rates, SoftBank’s solvency itself is slowly moving into focus. The cost to insure against a SoftBank default has been creeping higher in the past several months, recently reaching levels not seen since March of 2020.

The entertainment value of Masa Son’s antics aside, we flag these events because of their potentially systemic nature, and as a warning for what the consequences might be if he is ever forced to play this game in reverse. As anyone with experience in the VC sector can attest, Masa Son threw around so much money to so many startups at such eye-watering valuations that most other VC firms were forced to follow suit, creating a self-reinforcing pattern of ever-higher valuation comparisons as the basis for the pricing of the next hot deal. We suspect the bubble in the private sector is even bigger than the one transpiring in the public markets.

We conclude with some thoughts on how a potential collapse in private valuations might put downward pressure on the public markets. Several large and well-known hedge funds have seen the allure of alpha in the private markets and have invested accordingly. Such crossover funds hold a mix of both private and public securities, selling allocators on the idea that excess returns can be achieved with manageable incremental risk. Mega funds Coatue Management and Tiger Global Management have been particularly active in this way, and both have been in the news recently. Here’s an interesting story on Coatue that caught our eye last week:

“Coatue Management investors are pulling $250 million from the firm’s main hedge fund. But they won’t get all the money they’re asking for. Assets invested in private companies will be withheld by Coatue and placed in a side-pocket, according to people familiar with the matter. That amounts to 13% of the cash being sought by clients -- a total of $33 million.

Coatue’s decision comes as the firm, like many industry peers, has increasingly invested in private companies, hoping to see outsized gains when these enterprises go public. About 11% of Coatue’s main hedge fund, which ran $15 billion as of year-end, is comprised of private firms. But as market volatility increases asset managers may be forced to mark down the value of their non-public stakes.”

Dealing with redemptions is always challenging, and the danger of holding a mix of liquid and illiquid securities only exacerbates the problem. When cash needs to be produced in short order, one tends to discover just how much truth is in the price being carried on the books.

For its part, Tiger Global Management has been investing in private companies at a staggering pace, making it the most prolific VC investor in the world last year. Here’s how the Wall Street Journal reported on it last week:

“As an investor, Tiger Global surpassed all other venture firms last year, backing 335 deals, a more than fourfold increase from the 79 transactions it did in 2020, according to data provider CB Insights. The firm picked up the pace as this year began, doing two deals each business day into mid-February, the data show.”

We’ve heard the whispers from our friends in the VC sector about the crazy valuations Tiger is paying to close these deals, and one wonders just how much due diligence can be going on when you are doing two deals a day. Perhaps it is just a coincidence that Bloomberg recently reported on Tiger’s rough start to 2022:

“Chase Coleman’s Tiger Global Management posted a 10% decline for its flagship hedge fund last month, a significantly steeper drop than the broader market, according to people familiar with the matter. That follows a 14.8% swoon in January, extending its loss for the year to 23%.”

Most financial crises find their genesis in obscure parts of the markets that fly under the radar until it is too late to stop the contagion. Will the bubble in private market valuations be the catalyst for the next major downturn? We’ll be watching this space closely.

If you enjoy the work of Team Doomberg and have not yet signed up to receive new articles directly to your inbox, we encourage you to subscribe below. Thank you for being a reader!

√25 - √4 = √9 .... is it that non-believers in market deflate the valuation by square root? LOL

We have a valuation problem in the Alberta oil patch because of how corporations account for the liabilities around the cleanup of inactive and non-income generating, wells. It is not uncommon for the large, well financed, energy producing corps to package 1 or 2 good producing wells, with thousands of dud wells, all with negative valuations because of their clean up costs, and then selling the whole package for $1.00, to a small financially unstable producer. The problem arises at this point. How do they convince the Alberta Energy Regulator (AER) that there is enough value in the small corporation, so that the AER will okay the transfer of the licenses of the wells, without having to post security against future clean up liabilities? Simple. The larger corp gives the small corp 1% working interest in other producing wells that it owns but are not part of the $1.00 package. That separate deal doesn't require the AER's approval, but effectively raises the valuation of small corp., because they get to count FULL value of the 1% working interest wells. Once the AER licensing transfer request is approved, the 1% working interest becomes void. Financial gymnastics is the norm in the Alberta oil patch. It is very hard to determine who owns what, how much, and for how long of the assets. The liability of cleaning up over 100,000 inactive wells is estimated to be in the $70 billion dollars range, but it has been common for industry to just ignore that liability or in the minimum, to under estimate that liability. That liability if properly accounted for would effectively make over 50% of the current number of corporation in Alberta holding well licenses, to be insolvent.