Ctrl+Alt+Delete

Can Germany reboot its nuclear power industry?

“I’d like to see more optimism about the future!” – Friedrich Merz

In the least surprising development of 2024, the wind stopped blowing across Europe for an extended period in mid-December. Further research reveals that solar intensity is likewise reduced in the Northern Hemisphere during the winter months, especially at night. Disturbingly, even an infinite installed capacity of wind and solar energy facilities is of little use against the deportment of Mother Nature, and neither stilled turbines nor dormant solar panels can charge a cell phone, let alone power an entire country.

It is understandable—nay, just—that unserious countries like Germany and the UK should face their enthusiastically pursued consequences during such periods. Alas, like drowning swimmers in a crowded pool, they are dragging nearby victims into this latest emergency. For decades, European countries have been busy building interconnector cables between themselves, thus ensuring that several nations in the Old Continent got to share in the joy of seasonal energy poverty. The Norwegians were none too pleased:

“Norway’s two governing parties want to scrap an electricity interconnector to Denmark, with the junior coalition partner also calling for a renegotiation of power links to the UK and Germany, as sky-high prices trigger panic in the rich Nordic country. A lack of wind in Germany and the North Sea will push electricity prices in southern Norway to NKr13.16 ($1.18) per kilowatt hour on Thursday afternoon, their highest level since 2009 and almost 20 times their level just last week.

‘It’s an absolutely shit situation,’ said Norway’s energy minister Terje Aasland.

The ruling centre-left Labour party now says it wants to campaign in next year’s parliamentary election, set for September, to turn off electricity interconnectors to Denmark when they come up for renewal in 2026. Its junior coalition partner, the Centre party, has long demanded an end to the Danish connection and also wants to renegotiate existing interconnectors with the UK and Germany.”

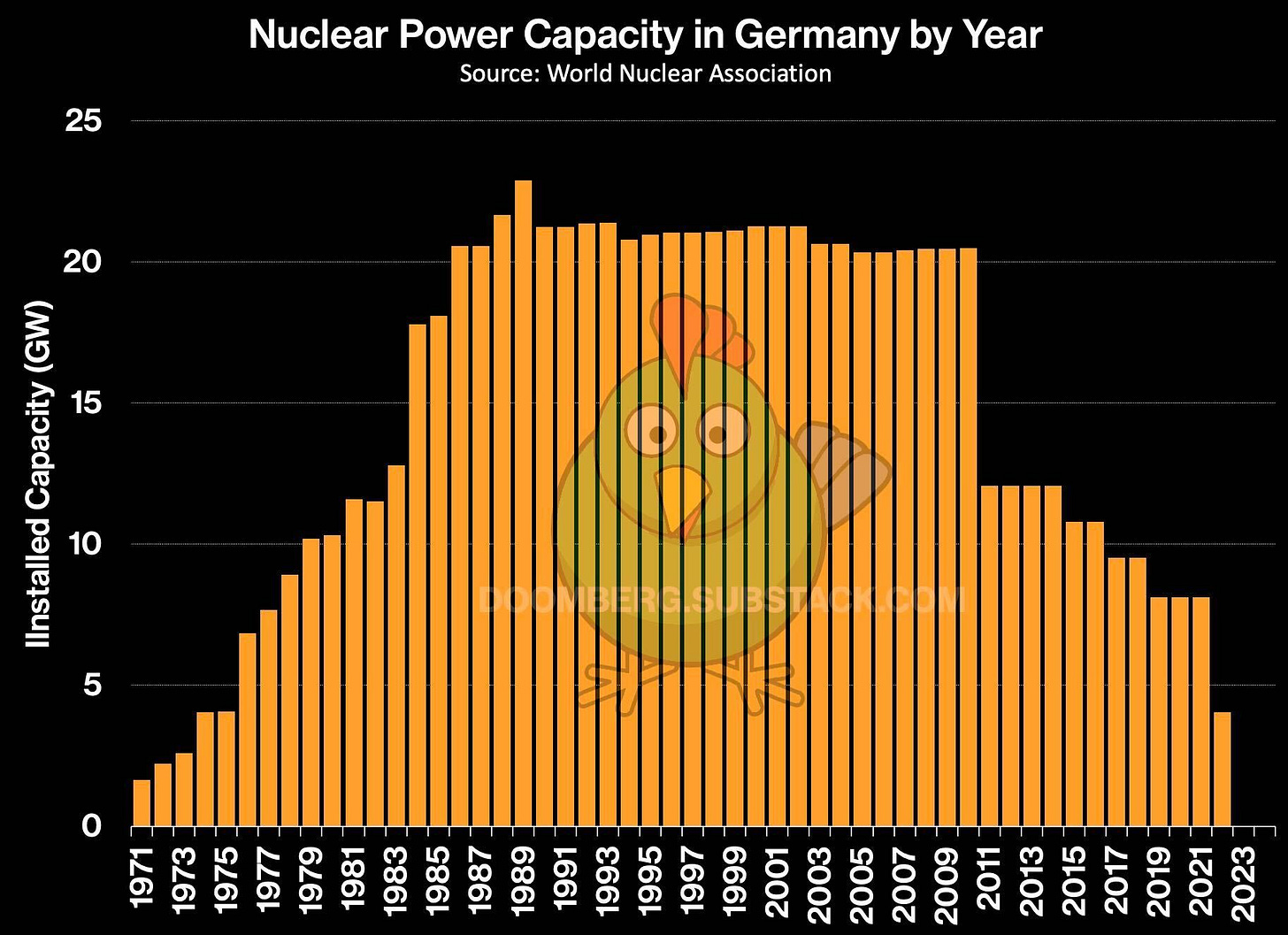

Sweden, a country that once embarked on closing its nuclear reactors before a bout of sanity kicked in, was also caught up in the crisis. Still operating 70% of its historical installed nuclear capacity, the country’s energy minister was swift to affix blame where it is justly due:

“Sweden is ready to introduce new measures to tackle the country's soaring energy prices, Energy Minister Ebba Busch announced on Thursday (12 December), blaming Germany's nuclear phase-out for the crisis in the country and at EU level….

‘I'm furious with the Germans,’ Busch told Swedish broadcaster SVT. ‘They have made a decision for their country, which they have the right to make. But it has had very serious consequences,’ she added.”

As deranged as Germany’s decisions have been, the question of whether its actions are irreversible often arises. How difficult would it be to restore any of the country’s once-formidable fleet of carbon-free nuclear reactors? With the collapse of the current government and elections a few weeks away, the issue might take center stage again. Let’s explore the technical, political, and financial barriers to such an outcome.