Drowning Swimmers

Will Norway risk going down with Europe’s sinking energy ship?

“I think frankly when it comes to chaos you ain't seen nothing yet.” – Nigel Farage

With the 1959 discovery of the giant Groningen natural gas field in the Netherlands, interest in the hydrocarbon potential of the North Sea rose dramatically. Experts had previously doubted the prospects, but suddenly a rush for resources was on. What stood in the way of full development was uncertainty over how to define the continental shelf boundaries, particularly between Britain and Norway. The issue was resolved on March 10, 1965, when the two countries signed an agreement based on the equidistance principle—a simple solution that ended the impasse.

How they managed their newfound bounties would prove decisive in shaping their economic trajectories over the next 60 years. By 1972, Norway had established a national oil company, Statoil (now Equinor), which collaborated extensively with international partners on oil and gas production. Beginning in 1996, surplus revenues were funneled into a sovereign wealth fund, kept largely out of the reach of day-to-day government spending. That fund now holds about $1.9 trillion in assets under management, making Norway one of the world’s richest countries.

Britain, by contrast, took a tax-and-regulate approach. Initially supportive of private-sector participation, the government provided generous incentives to encourage investment. But unlike Norway, tax revenues from North Sea oil and gas were perpetually spent as they came in to help balance the government’s books, with nothing set aside for future generations.

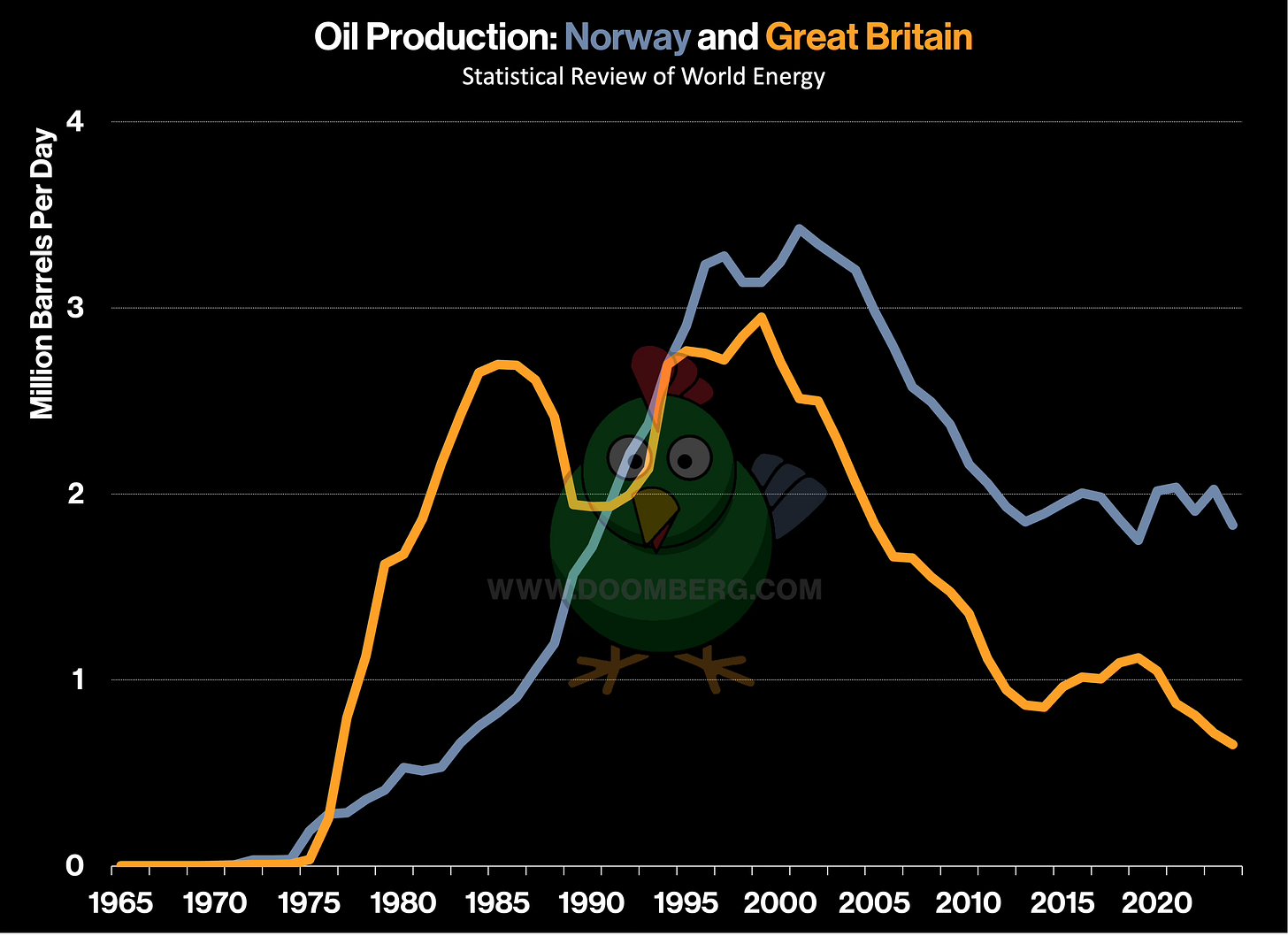

As decades passed and successive governments doubled down on a costly green energy transition, taxes and regulations on oil and gas companies doing business in Britain steadily ratcheted upward. Today, the system has become outright punitive: the combined marginal tax rate on income from British oil and gas extraction sits at 78%. Unsurprisingly, drilling activity is grinding to a halt, and the once-mighty British North Sea is in steep decline. Last year, Norway nearly tripled Britain’s oil production:

Norway’s prudent management of its national energy resources extends well beyond its hydrocarbon wealth. The country generates nearly all of its electricity from hydroelectric plants, which have provided Norwegians with some of the cheapest and most reliable electricity in the world for decades.

Heavy industries clustered around this advantage, with aluminum smelters, chemical factories, and fertilizer plants flocking to Norway to leverage its abundant and low-cost green power. In effect, the country transformed its natural geography into an enduring competitive edge, turning plentiful water flows into a foundation for both prosperity and industrial strength.

Although Norway shrewdly avoided becoming a full-fledged member of the European Union (EU), it did join the European Economic Area and has aligned its climate agenda with Brussels. The water behind Norway’s many dams makes for a tempting “battery” for the grids of Europe and Britain, stuffed as those countries are with intermittent renewables. Over time—and especially since 2021—Norway has increasingly integrated its electricity with its neighbors and, unsurprisingly, has begun to feel the consequences.

Next week, Norway holds a pivotal parliamentary election that could halt and reverse this trend. Among many hotly debated issues is whether the country’s abundant natural resources should primarily benefit its own citizens. In other words, another wave of nationalism might soon crash upon Europe’s shores. Given the high stakes, let’s head to Oslo and dig deeper.