Eight is Enough

Will the EPA outsource itself to California before Trump’s inauguration?

“I can promise you that when I go to Sacramento, I will pump up Sacramento.” – Arnold Schwarzenegger

If they could be injected with truth serum, one wonders whether the high-profile Democratic governors of certain US states would admit to being not entirely disappointed with the outcome of the presidential election. Had Vice President Kamala Harris emerged victorious, those with national ambitions would have had to almost certainly wait until 2032 for a shot at the big chair. With President-elect Donald Trump returning to office, both parties are set for open, competitive primaries next time around, and don’t doubt for a second that jockeying for those contests is already well underway.

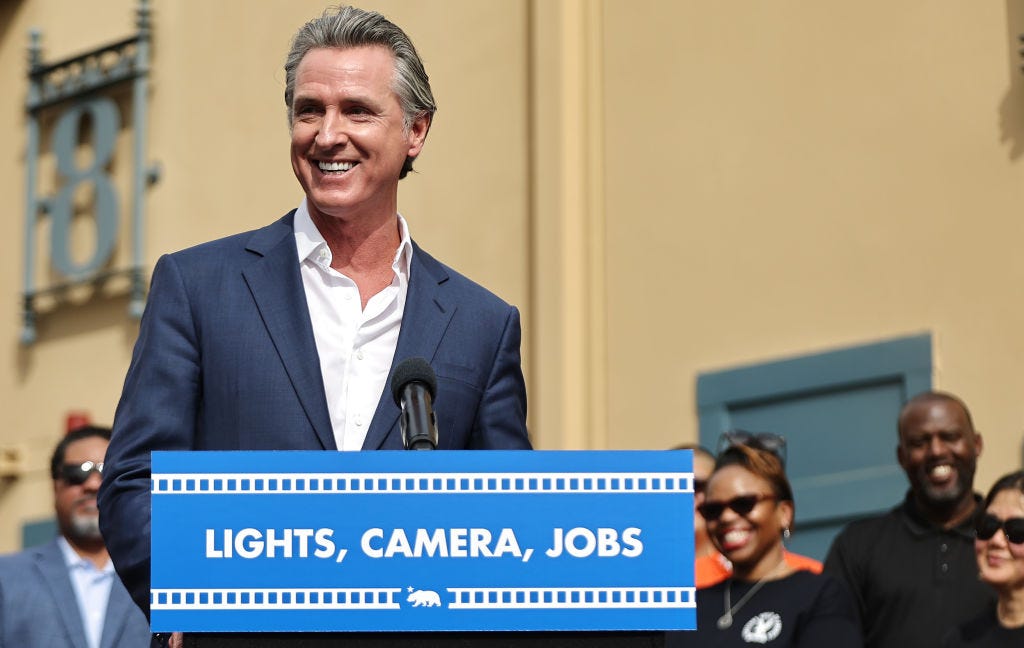

Among the more determined aspirants is California Governor Gavin Newsom, whose political biography checks all the big blue boxes. After succeeding Willie Brown as mayor of San Francisco in 2004 and winning re-election four years later, Newsom was elected lieutenant governor of the Golden State under Jerry Brown. After two terms in that position, he secured the state’s top role in the 2018 election and triumphed again in 2022. Having maxed out his eligibility to serve as governor, Newsom will be looking for his next gig just as the 2028 nomination season is spooling up, and one would be foolish to underestimate his chances. Whatever your view of his politics, he is a formidable politician, a sharp debater, and backed by big money.

Presumably, the Democratic candidate who can best claim to have blunted the Trump agenda will be in a highly advantageous position to secure the nomination next time around. In this regard, Newsom holds a strong hand because of a decades-old federal law that treats California differently than every other state on certain high-stakes environmental issues. We turn to the Congressional Research Service for a helpful backgrounder:

“In the Air Quality Act of 1967… later amended to the Clean Air Act (CAA)… Congress preempted state governments from adopting their own air pollutant emissions standards for new motor vehicles and new motor vehicle engines. Notwithstanding, Congress decided to provide an exemption for the State of California. Under CAA Section 209, California can apply to the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for a waiver from the federal preemption, and EPA is to grant this waiver absent certain disqualifying conditions. As of 2024, California has used this authority to receive more than 100 federal preemption waivers for new and amended state-level vehicle emissions standards. Further… Congress allowed other states to adopt California’s vehicle emissions standards under certain conditions. As of 2024, 17 states and the District of Columbia have used the authority under CAA Section 177 to adopt some subset of California’s standards.”

To the chagrin of conservatives, Section 209 of the CAA has proven an effective loophole, used by those on the progressive environmental left to impose upon the rest of the country the edicts of the California Air Resources Board (CARB). With manufacturers loath to create bespoke products for individual states, the CARB edicts effectively supersede those of the EPA, and entire industries have been forced to retool once the latter grants waivers to the former. For a sense of the upcoming war that motivates our current dispatch, we return to President Trump’s first term, when he launched a gambit to change the status quo by executive dictate:

“President Trump said Wednesday his administration is revoking a waiver that allowed California to set its own standards for automobile emissions — a move that could derail a years-long push to produce more fuel efficient cars. In a series of tweets Wednesday, Trump said the action will result in vehicles that are safer and cheaper, and that ‘there will be very little difference in emissions between the California standard and the new U.S. standard.’

Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Andrew Wheeler telegraphed the planned announcement on Tuesday. Speaking to the National Automobile Dealers Association, he said, ‘In the very near future, the Trump administration will begin taking the steps necessary to establish one set of national fuel-economy standards.’”

Although Trump’s maneuver was legally dubious and likely would have been stopped by the courts, the Biden administration reversed the revocation upon assuming power in January of 2021, and no real precedent was set.

Since Biden took office, the relationship between CARB and the EPA has been mostly business as usual, with one important exception. For reasons few can articulate, Biden’s EPA has slow-rolled the approval of eight major CARB waiver applications currently sitting before it—some have been waiting for several years—and how that backlog will be handled has taken on renewed urgency in the aftermath of Trump’s electoral triumph. Many of these proposed waivers would radically alter the everyday life of average Americans and transfer enormous power from Washington to Sacramento, yet the issue is not on most people’s radar. Let’s put it on yours.