Flying High

No, we won’t be making jet fuel from CO2.

“Zeal without knowledge is fire without light.” – Thomas Fuller

The struggle for oil was a driving force in World War II, dictating much of the strategy for the major parties involved. The Japanese went to war as a direct consequence of President Roosevelt’s oil embargo, while Germany’s Hitler became obsessed with the oil fields of Romania and the Caucasus, leading to several decisions that historians now believe precipitated the ultimate defeat of the Third Reich. Tactical blunders aside, the strategic focus on oil is perfectly sensible—war “is nothing more than the concentrated conveyance of destructive energy, and the history of war can best be understood through the lens of primary energy development, its efficient conversion into weapons, and its resulting targeted delivery against the enemy.” Planes, tanks, and supply vehicles would quickly grind to a halt without aviation fuel, diesel, and gasoline.

For Germany, the lack of domestic oil supplies presented a grave challenge, and Hitler leaned heavily on some of the world’s best chemists and engineers to partially circumvent the problem by leveraging the country’s comparatively abundant supply of coal. In 1913, German chemist Friedrich Bergius invented direct coal liquefication to make gasoline and aviation fuel from lignite. In the early 1920s, scientists Franz Fischer and Hans Tropsch discovered how to make diesel and lubrication oil from coal via the production of syngas, a mixture of carbon monoxide and hydrogen. In 1936, Hitler ordered these technologies into full industrial production, and several dozen synthetic fuel plants were built across the country, prolonging Germany’s viability in the war. Ultimately, the massive oil advantage held by the Allies proved decisive.

Germany’s foray into the world of synthetic fuels proved two things. First, with enough energy and money, virtually anything is possible at the molecular level. Second, no matter how talented the army of chemists you have at your disposal, those energetic and monetary bills must eventually be paid. The net energy made available to the Allies by directly pumping and refining oil was vastly superior to the meager net energy profit achieved by transforming coal into fuels. Making coal into something it inherently isn’t comes with substantial penalties, and much of the embodied potential energy of Germany’s coal supply was wasted in the transformation process. Thermodynamics is a decidedly ruthless referee.

Our current batch of political and scientific actors routinely ignore these basic lessons as they recycle rejected ideas of the past into the basis for new policy, most prodigiously as they seek to eliminate fossil fuels. Nowhere is this foolishness more pronounced than in the rebirth of the synthetic fuels concept, repackaged for our modern sensibilities with the incredibly silly moniker “eFuels.” Instead of making synthetic fuels from coal (an energy source), today’s reincarnation involves using CO2 (an energy sink) as a primary feedstock. We turn to the eFuels Alliance for a helpful primer on this “new” energy utopia (emphasis added throughout):

“eFuels are produced with the help of electricity from renewable energy sources, water and CO2 from the air. In contrast to conventional fuels, they do not release additional CO2 but are climate neutral in the entire balance. Thanks to their compatibility with today’s internal combustion engines, eFuels can also power vehicles, airplanes and ships, thus allowing them to continue to operate but in a climate-friendly manner. The same applies to all heating systems that use liquid and gaseous fuels. Existing transport, distribution and fuel/gas infrastructures can also continue to be used.”

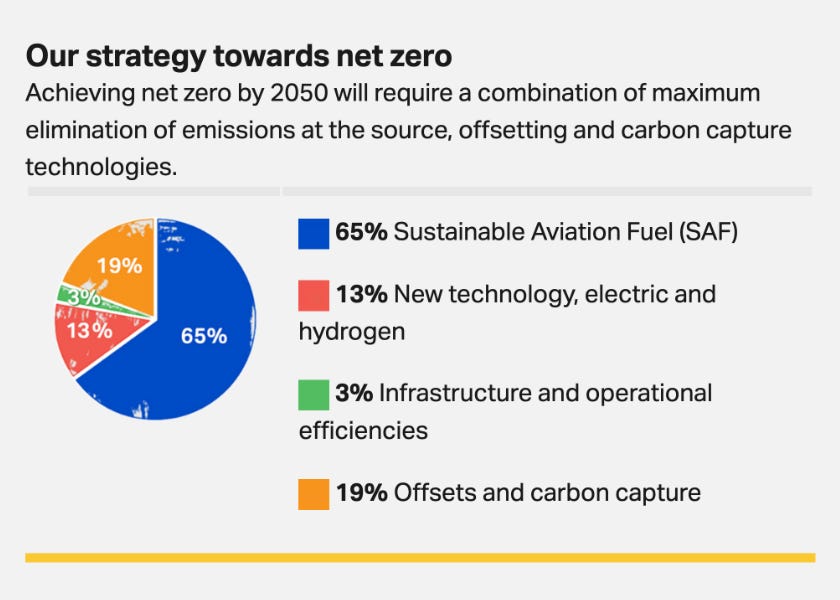

Perhaps no industry is more excited by the concept of eFuels than the aviation sector, which accounts for between 2-3% of global annual carbon emissions. Faced with the impossible task of flying passengers and cargo around the world while still hitting their 2050 Net Zero targets, airline companies are desperate for ways to pretend they can use anything other than jet fuel. According to a recent report by the International Air Transport Association, the development of Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) accounts for 65% of the industry’s future abatement plans, and much of this planned SAF is intended to come from eFuels.

How insane is all this happy talk? What would a process workflow for making jet fuel from CO2 entail? What sort of companies are being funded in the industry’s desperate attempt to fend off the carbon counters? Let’s ground some high-flying claims in lucid reality.