Hold My Beer

“The fact that hype exists doesn't prove that something is not important.” – Vilayanur Ramachandran

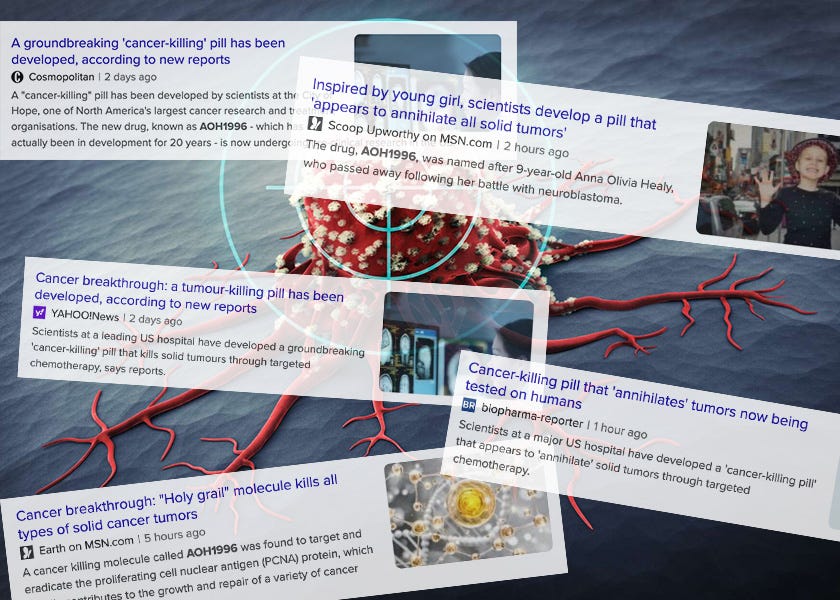

When we took pen to paper last week to assess the breaking claim that a room-temperature superconductor had been synthesized in the lab by a group of South Korean researchers, we opened by noting, “Roughly once a quarter, a proclaimed advance in the world of science makes the leap into the mainstream media’s hype cycle, triggering a wave of inquiries from readers for our view on the significance of the discovery.” As it turns out, the quarterly cadence has been broken and we quickly have another mammoth claim to delve into (emphasis added throughout):

“A ‘cancer-killing pill’ has appeared to ‘annihilate’ solid tumours in early research – leaving healthy cells unaffected. The new drug has been in development for 20 years, and is now undergoing pre-clinical research in the US.

Known as AOH1996, it targets a cancerous variant of a protein called proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA). In its mutated form, PCNA is ‘critical’ in the replication of DNA, and the repair of all ‘expanding tumours.’”

Each year in the US alone, cancer is diagnosed in nearly two million people and claims approximately 600,000 lives. Although estimates vary, the size of the global oncology drug market is generally pegged at between $150-200 billion, making it the largest and most lucrative drug class by a wide margin. It is not uncommon for particularly effective cancer treatments to cost in excess of $200,000 per year, forcing patients—and their insurance companies—to make difficult tradeoffs as they chart their response to the unwelcome diagnosis. As anyone who has directly engaged in these difficult contemplations can attest, cancer treatment is a complex mix of science, ethics, and economics.

Given the size of the prize, researchers in the field routinely hype their findings, likening otherwise pedestrian advances to the discovery of a magic elixir. The latest details emerging from AOH1996, though, present several aspects that warrant a deeper analysis.

As long-time pharmaceutical blogger and chemist Derek Lowe noted in his popular “In the Pipeline” commentary, the initial data are quite intriguing. When tested in mice and dogs, the compound passed toxicity screening at levels six times higher than the effective dose in either species, a critical result that paves the way for human trials. It showed efficacy in 70 different cancer cell lines, lending support to the hypothesis that AOH1996 might attack a universal weakness common to all cancers. The testing also indicated that combining the new drug with existing chemotherapy agents boosted the efficacy of the latter, opening up the prospect of powerful drug cocktails with synergistic effects that could further improve patient outcomes.

As tantalizing as these results appear, it can be challenging to get a true gauge of the significance of these early developments. Our “straightforward five-question framework to quickly assess whether advances such as these are likely to pan out” served us well for the room-temperature superconductor claims last week. It is just as useful for scientific advances in the fields of energy, medicine, and many others, so let’s apply this cross-disciplinary model to the AOH1996 potential “cure” for cancer.