In the Aggregate

The US federal government moves forward to dismantle the climate change movement’s levers of power.

“A precedent embalms a principle.” – Benjamin Disraeli

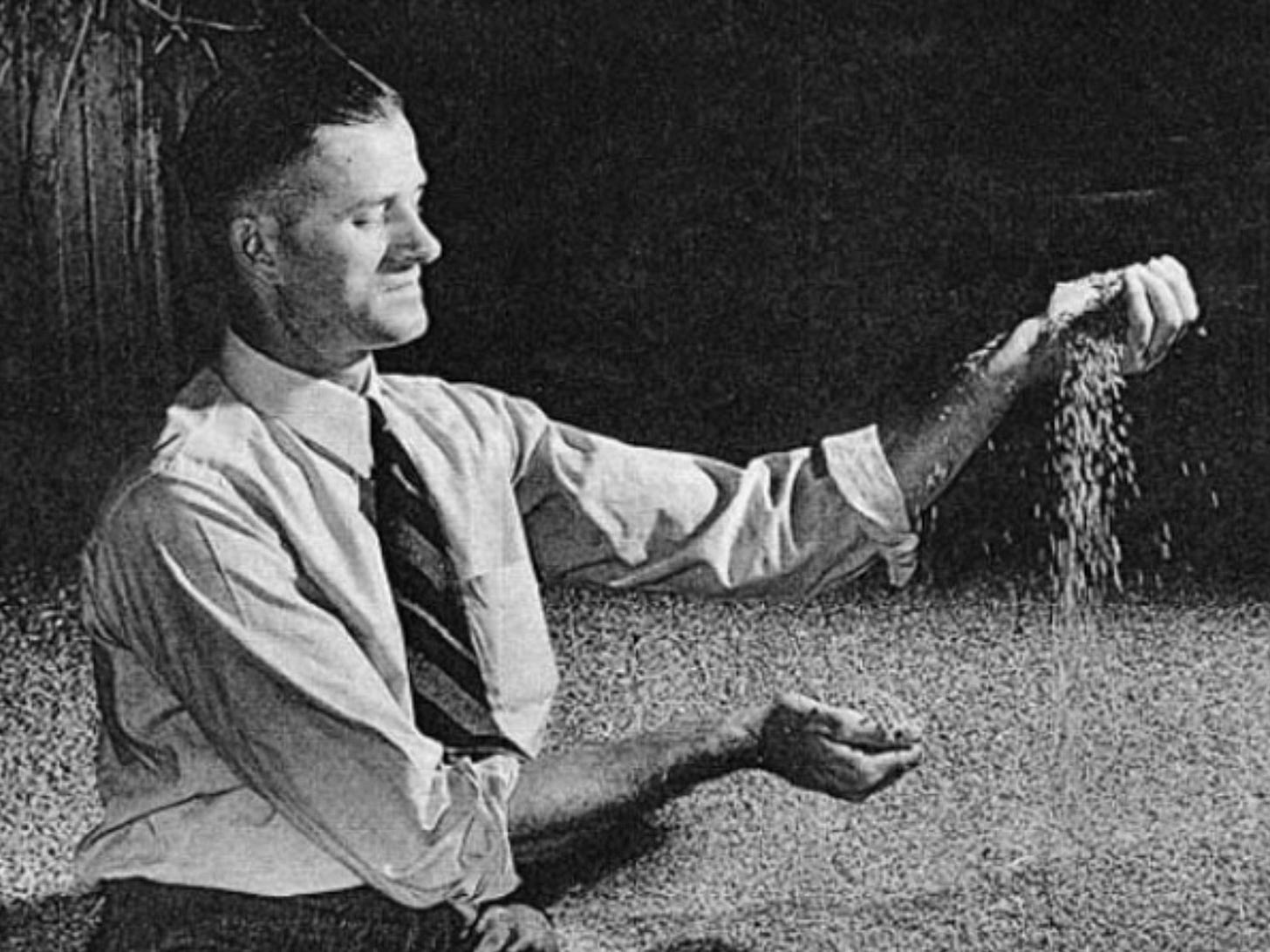

Roscoe Curtiss Filburn (1902–1987) was a fifth-generation Ohio farmer. Nothing about the 95-acre plot of land he worked was particularly remarkable, but Filburn would ultimately play a central role in a legal case that fundamentally altered the arc of US history. For the 1940-41 growing season, he planted 23 acres of wheat, a crop he did not intend to sell on the open market. Instead, he judged that to be the amount his family and farm animals required for food, with a bit set aside to seed the next cycle. The management of his private farm had always been the exclusive purview of the family, and Filburn saw no reason to seek permission from the US federal government to do with his property as he saw fit.

Despite the fact that the wheat never left his farm, the government told Filburn his actions ran afoul of the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938, one of a series of constitutionally dubious New Deal laws passed by Congress at the urging of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR). Bureaucrats at the Department of Agriculture used the law to determine that Filburn was allowed no more than 11.1 acres of wheat and fined him $117.11 for exceeding his centrally planned quota. The price of gold was $35 per ounce in 1941, making his fine the equivalent of nearly $13,000 in today’s hard money.

The FDR administration had decided that higher wheat prices were in the national interest and independent actors like Filburn were a threat to that objective. Filburn sued the head of the US Department of Agriculture, Claude Wickard, and initially prevailed in federal court. Wickard appealed to the US Supreme Court, and in November of 1942, the Court—perhaps mindful of FDR’s threats to pack it should his ambitions be impeded—handed down one of the most egregiously unconstitutional decisions in American history. It ruled that while Filburn’s actions in no way directly impacted interstate commerce, the aggregate impact of too many farmers acting similarly would. Therefore, the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938 was deemed constitutional, and Filburn’s fine must be paid.

As described by Utah Senator Mike Lee in his outstanding book The Freedom Agenda, this expansive reading of the Commerce Clause explains how the US federal government now infiltrates nearly all aspects of private life:

“Wickard v. Filburn had sweeping implications. In light of that decision—which has never been reversed—Congress may, without interference from the courts, use the Commerce Clause to regulate any activity that, when measured in the aggregate, substantially affects interstate commerce. Under that standard, almost every human endeavor, even non-economic activity, is potentially subject to federal regulation under the Commerce Clause.

With this ruling, the Supreme Court sent Congress an unmistakable message: ‘Feel free to do whatever you want under the Commerce Clause; we won’t second-guess your judgment.’ In the wake of Wickard, members of Congress stopped asking the question of whether they could regulate anything because the default answer was a resounding ‘yes.’ They stopped asking whether they could, and then eventually stopped asking whether they should. And thus the constitutional debate in Congress—and along with it, the time-honored, constitutional concept of limited federal power—steadily faded into obscurity.”

Any government authorized to interfere so vastly in everyday life inevitably will, and an army of federal administrators has since been deputized for the task. The Code of Federal Regulations now spans more than 190,000 pages across 245 volumes—up from a mere 4 volumes and 15,000 pages in 1940—and dictates, with often contradictory edicts, how life shall be lived across all the US states. The US Constitution, a document whose stated intent was to proactively limit the powers of the central government, was thus utterly perverted.

Congress’ confidence that it could pass virtually any law so long as it met the aggregation principle was compounded by its willingness to outsource much of the interpretation and implementation of such laws to the so-called experts employed by federal agencies. This itself is constitutionally dubious, but nonetheless became standard practice in Washington.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), among many other federal agencies, has wrangled tremendous power through these dual drifts. The Endangered Species Act (ESA) has been used ad nauseam to usurp state-level oversight of plainly intrastate activities and those not directly considered commerce. Further showcasing the risks of congressional outsourcing, the EPA’s reinterpretation of the Clean Air Act to conclude that carbon dioxide is a pollutant violates all fair readings of the original bill and the debate surrounding its passage, neither of which can plausibly support such a conclusion.

Perhaps weary of what its predecessors had unleashed, the current Supreme Court has been chipping away at the most egregious overreaches, beginning with limits on what Congress can delegate. In West Virginia v. EPA (2022), the Court formally recognized what has become known as the major questions doctrine, requiring specific congressional approval for actions of “vast economic and political significance.” The Court then used this reasoning in 2024 to strike down the Chevron doctrine (Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo), which had previously empowered agencies to interpret statutory ambiguities, opening the door to their largesse.

In July, President Trump’s EPA, under Administrator Lee Zeldin, controversially proposed to rescind the EPA’s carbon emissions endangerment finding. This directive will retest the major questions doctrine in a significant way. Although the legacy media has focused almost exclusively on the administration’s evaluation of whether the scientific basis of climate change is truly settled, the question of whether the EPA needs specific congressional authority to issue regulations is, in our view, the most significant threat to the climate change agenda. Already, the Department of the Interior under Secretary Doug Burgum is proceeding as though victory is in hand, announcing on Monday that 13.1 million acres of federal land will be made available for coal development project leases.

If the Trump administration ultimately prevails, it would deliver a devastating blow to the climate change movement and unleash a torrent of hydrocarbon development. Still, this amounts to no more than a flesh wound to the gross constitutional imbalances seeded by FDR. To truly reshape federal power closer to what the framers intended would require an overthrow of Wickard v. Filburn—something a dedicated group of conservative legal scholars has been agitating for since the decision was first handed down more than 80 years ago. In early 2024, a new attempt at dismantling the precedent was launched:

“One of the worst decisions in Supreme Court history might finally be overturned.

Filed in January 2024, John Ream v. U.S. Department of the Treasury could cast aside Wickard v. Filburn (1942) could put an end to the Court’s rampant abuse of the Constitution’s Commerce Clause to justify whatever Congress wants to do.

The plaintiff is asking for declaratory and injunctive relief to overturn the current federal ban on distilling alcoholic beverages at home for personal and family consumption. Mr. Ream wants to produce rye and bourbon and has no plans to sell or offer it to the public. He believes that this prohibition exceeds the powers of Congress under both Article I and the 10th Amendment.”

Among the conservative legal organizations filing supporting briefs on behalf of the plaintiff are the Americans for Prosperity Foundation, the Cato Institute, the Center for Individual Rights, the Liberty Justice Center, and the Southeastern Legal Foundation. As of this writing, the case is making its way through the courts, and it remains to be seen whether the US Supreme Court will ever hear it. If it does, a winner-take-all legal brawl would undoubtedly ensue.

“♡ Like” this piece and enjoy some moonshine.

Doomy's article is a subject that makes my heart thump.

I agree with every sentence. When people think of liberties they often think exclusively of political liberties like speech, association, religion, and so forth. These are very important. However, what are these worth without economic liberty? Wickard v Filburn made certain that the federal government could regulate- in others words ban- all economic activity. In addition to being a major suppression of liberty it's also an end run around the Takings Clause. Think back to Obama's pledge to destroy the coal industry and then following through on that threat. Billions of dollars of property were ruined when he shuttered power plants and coal mines. Tens of thousands of jobs were lost. Much of the big mining equipment lost the bulk of its value and was sold for parts or exported for pennies on the dollar. Such is the fruit of Wickard v Filburn and its allied cases.

But it's not just SCOTUS that got it wrong. After all, it was Congress who passed the law and the President who signed it. No future Congress repealed it. Our nation has been teaching its youth that this is a legitimate power of the federal government, that economic liberties are, like the 2nd amendment, second class liberties. Even if SCOTUS overturns Wickard we still have to contend with what's in the hearts of Americans with regard to economic liberty. Will they elect legislators who support passing such a law again?

So much work needs to be done to instruct the nation on our full heritage of liberty, including the right to work in any trade you wish without government destroying your career. You don't have to be in the coal industry to fear that possibility. During Covid the Constitution became an artifact for a time and many were told they were "non-essential" workers. Here's to hope that SCOTUS can strike a blow and that friends of economic liberty to persuade their fellow Americans that those liberties are as important as the ones in the Bill of Rights.

Envisioning how this would change things in DC, I can see a future where the federal government becomes a shadow of its former self. if there is any time when this could happen, it seems this administration is the best chance we have. Here's hoping!!!