Intelligent Design

Ohio gets the data center game right.

“This just in: Beverly Hills 90210, Cleveland Browns 3.” – Colin Mochrie

David Tod was in his mid-30s in 1841 when he inherited his family farm in Youngstown, Ohio, a bequest that would forever alter the arc of the region’s economic history. The farm was rich with seams of block coal, a bituminous variety that manifests as large, coarse lumps or cubical “blocks” rather than small fragments. Such coal proved slow-burning and gave off tremendous heat, making it ideal for direct use in steelmaking blast furnaces. Not only did Tod set about mining the stuff, but he also aggressively marketed what became known as Brier Hill coal in Cleveland and other nearby industrial centers, convincing ironmasters to switch to the cheaper, superior, homegrown fuel.

Recognizing the importance of logistics in getting his coal to market, Tod became heavily involved in the shipping and rail businesses, eventually becoming president of the Cleveland & Mahoning Railroad, a company that accelerated industrialization in both northeast Ohio and the wider Great Lakes region and transformed Youngstown–Warren–Cleveland into a coherent industrial corridor. By 1862, Tod was elected governor of Ohio.

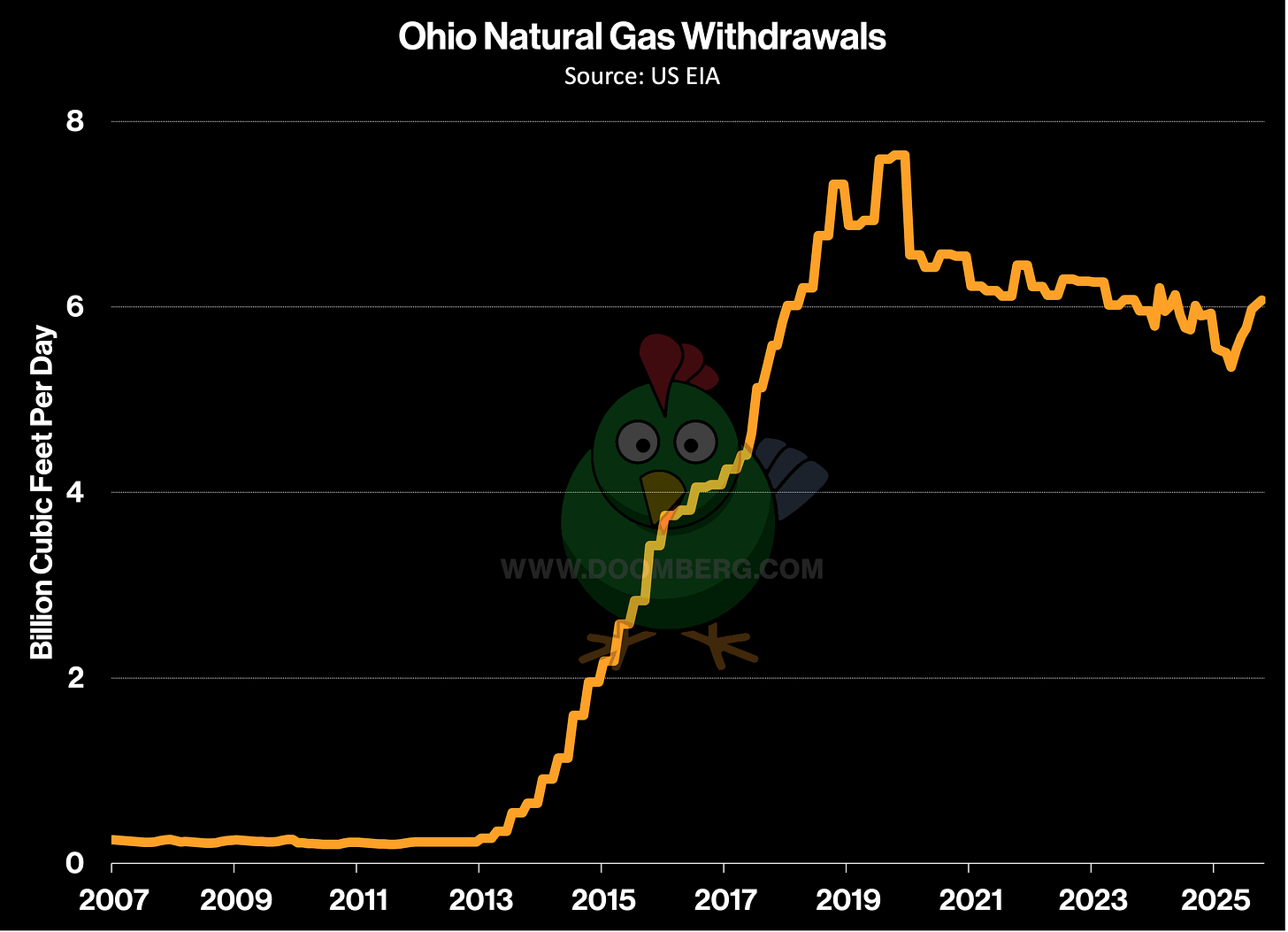

Although Ohio’s manufacturing base has been leveled in recent decades by attacks on coal as a fuel, deindustrialization due to globalization, and stricter environmental standards imposed on the state’s heavy industries, the shale revolution has breathed new life into the area’s prospects. The gas-rich Marcellus, Utica, and Ohio shale formations span much of the state, which has enjoyed a boom in natural gas production.

According to the latest data from the US Energy Information Administration (EIA), gas withdrawals—the broadest definition of production—currently stand at 6 billion cubic feet per day (bcf/d), up from practically nothing a little more than a decade ago. This is down from its pre-Covid peak of 7.5 bcf/d, a decline driven primarily by the glut of associated natural gas being produced in other parts of the US. The geologic potential to vastly increase production in Ohio is significant.

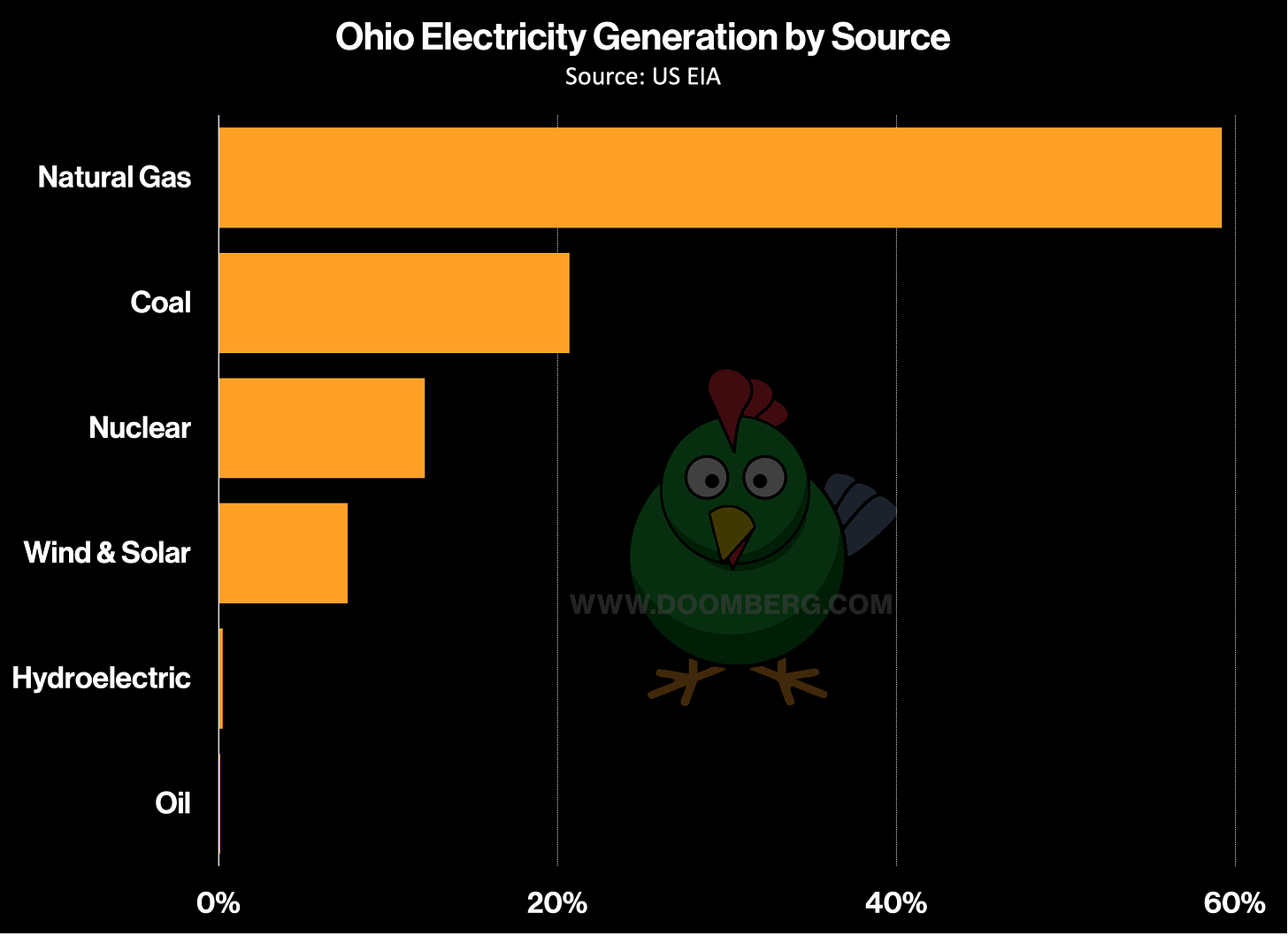

Ohio’s leaders have parlayed this newfound gas bounty into cheap electricity production. According to EIA data, nearly 60% of the state’s electricity is generated from natural gas, a fuel that provides both baseload and dispatchable power. Coal and nuclear power supply about 80% of the remaining balance, while wind and solar combined contribute just under 8% of total generation. Of course, Ohio does not operate its grid in a vacuum, and local price dynamics are heavily influenced by the Pennsylvania–New Jersey–Maryland (PJM) regional transmission organization, of which it is a member.

Given this fact set, Ohio would seem an ideal place for large data centers to set up shop. Indeed, almost unique among US states, Ohio’s political leaders have created a regulatory framework that sets the stage for a massive boom in the construction of such facilities while working to protect consumers. It also validates a prediction we made more than a year ago about how data centers would evolve to power themselves. In our view, virtually all energy-rich states will soon have to follow Ohio’s model. Let’s head to the Buckeye State and discover the details.