New England is an Energy Crisis Waiting to Happen

“A lot of people like snow. I find it to be an unnecessary freezing of water.” – Carl Reiner

At its core, the human body is a symphony of chemical reactions. The complexities and interdependencies of the molecular machinery that makes our bodies function are almost too staggering to ponder. As any chemist can attest, chemical reactions are usually quite sensitive to temperature, and sensitivity to temperature varies substantially across reaction pathways. As such, temperature control not only dictates reaction rates, but it also influences product and byproduct distributions. At one temperature, two reagents might react cleanly to produce a desired product with high purity. At a different temperature, an undesirable pathway might become more kinetically favored, leading to the accumulation of unwanted impurities.

One of the miracles of the body is its ability to maintain strict internal temperature control, which allows it to regulate the speed and product distributions of the myriad of chemical reactions that are occurring inside you as you read this. The equilibria are delicate, so much so that fluctuations of a mere few degrees can be fatal. This concept of “normal” body temperature is widely understood, but its direct, vital connection to the core chemical reactions occurring inside you is less well known.

Because internal temperature is critical to sustaining life, the body has developed elaborate heat management systems, including discomfort nudges (like shivering and sweating) that are meant to directly generate or shed heat and motivate you to relocate to a more suitable environment. If you stand outside for a few minutes in the winter wearing nothing but shorts and a t-shirt, you become uncomfortable rather quickly. Return inside to a warm fire and a rewarding comfort envelops you. Just don’t get too close to the fire, lest the body be forced to nudge you back outside.

Thermal comfort is the technical phrase that describes the human need to maintain a reasonable temperature and humidity environment, and it is generally accepted that people are most comfortable when the temperature is between 67°F and 82°F and the humidity is between 30% and 60%. It should come as no surprise to most readers that we invest a staggering amount of energy on heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) to keep ourselves in such favorable settings. The US Department of Energy estimates that 40% of the country’s CO2 emissions can be traced back to the need to achieve thermal comfort, significantly more energy than is used in the transportation sector. When we at Doomberg say energy is life, we aren’t just referencing the energy that goes into producing food or clean water – exposure to the elements and lack of thermal control will kill you much faster than a shortage of either of those.

Consider Boston, Massachusetts, the unofficial capital of New England (for our international readers, New England consists of six states in the US Northeast, namely Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont). Given its northern latitude, the citizens of Boston experience cold and sometimes brutal winters, but more reasonable summers. Globally, far more people die from exposure to cold than to heat, and this makes winter energy policy especially consequential. In the chart below, we’ve plotted the daily average high and low temperatures for the city and overlaid the thermal comfort zone for easy reference. Not surprisingly, the coldest months of the year are December, January, and February. During these months, an enormous amount of energy is consumed as the population seeks to achieve thermal comfort, and the amount of energy needed to do this is bounded by the laws of physics – it scales with the delta from the thermal comfort zone – and, as a practical matter, the tactics deployed at the extremes are highly inefficient.

In her excellent book Shorting the Grid: The Hidden Fragility of Our Electric Grid, Meredith Angwin describes how a combination of bad policy, complicated governance, and dense bureaucracy has made the entire electric grid of New England incredibly vulnerable to collapse, especially during winter cold snaps (you can buy Angwin’s book here and follow her Twitter account here). She tells the story of how Regional Transmission Organizations (RTOs) like ISO New England have evolved to oversee bulk electric power systems and transmission lines, and how producers of electricity must subordinate their natural gas consumption for use in home heating during extreme cold weather events. Of course, the demand for electricity skyrockets during these same extreme events as people supplement their home heating needs with electric space heaters, further exacerbating the problem.

Angwin goes on the tell the story of how New England’s electric grid nearly collapsed during cold snaps in late December 2017 and early January 2018. In the book, she quotes from an op-ed she wrote for the Valley News shortly after the incident (emphasis added throughout this piece):

“Around 5:00 P.M. on January 6, 2018, I snapped a light on as the sun went down. The temperature was around minus 8 degrees Fahrenheit. It had been zero at lunchtime and would be minus 15 the next morning. As usual, the light went on. As grid operator ISO New England had planned, oil had saved the grid. During that very cold week, about one-third of New England’s electricity came from burning oil. The people at ISO-NE might think it is unfair to say that they planned to save the grid with oil, but they did, because of the Winter Reliability Program.”

She goes on to describe that while burning oil had averted disaster, it had only barely done so. The grid was hours away from rolling blackouts before the weather thankfully turned warmer. The book then covers the broken interplay between policy, markets, and fuel security, how renewables impact the grid, and her thoughts on a more rational path forward. It is well worth a full read.

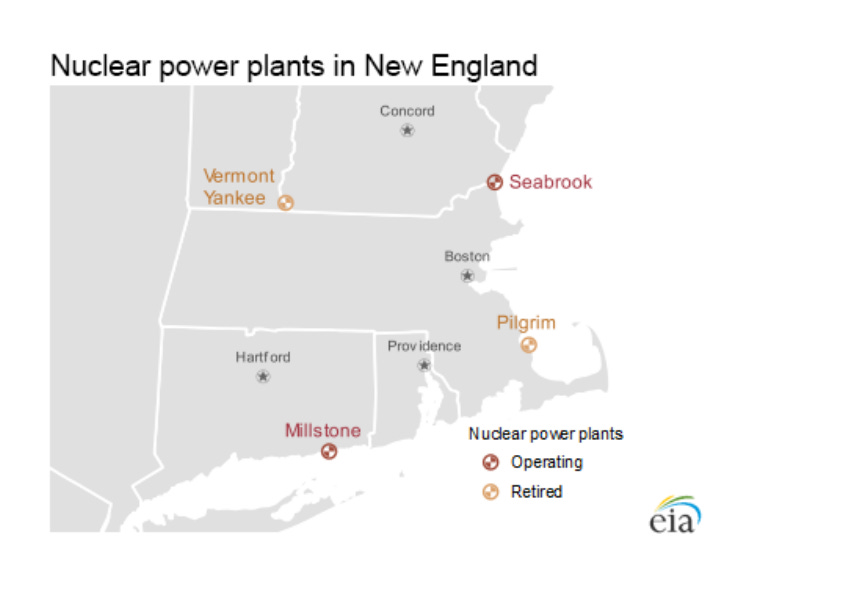

You would think that the near collapse of their energy grid would have motivated the good people of New England to get serious about shoring up their energy needs ahead of future cold snaps. You would be wrong. Instead, they have set about the task of systematically dismantling existing critical infrastructure and blocking the development of proven technologies. In 2019, the Pilgrim Nuclear Power Station was shuttered, leaving New England with only two nuclear power facilities. There are no plans to build more.

More urgently, virtually every attempt to expand the region’s natural gas pipeline infrastructure has been delayed, blocked, or abandoned. Here’s a sobering report from InsideSources from mid-2019 that describes the situation:

“As activists become more adept at enlisting government in their war on oil and gas pipelines, even small projects are becoming difficult to build.

Last month, voters in Longmeadow, Mass., approved a non-binding ballot measure encouraging the town to buy land to block a local natural gas metering and transfer station.

This past Earth Day, the mayor of Holyoke, Mass., announced his opposition to a proposed 2.1-mile, 12-inch natural gas pipeline that would increase capacity to meet rising demand. He asked federal regulators to reject the pipeline.

In March, the Bristol, Vt., Selectboard voted to cancel a license agreement with Vermont Gas that would have allowed Bristol residents to connect to a gas line that runs from Colchester to Middlebury, vtdigger.com reported.

From large, interstate pipelines to small lines connecting towns and neighborhoods, anti-fossil fuel activists have proven highly successful at blocking, through regulations or lawsuits, new natural gas infrastructure in the Northeastern United States.”

Just last month, voters in Maine killed an electricity transmission line project that would have brought renewable hydro power from Quebec to Massachusetts. Here’s a report from the Boston Globe:

“In what appears to be a stunning setback to Massachusetts’ climate goals, Maine voters on Tuesday rejected a referendum on a transmission line that would bring hydroelectric energy from Canada to the Bay State.

As of just before midnight, with 421 of the state’s 571 precincts reporting, a “yes” vote to stop the $1 billion project that is already under construction had garnered 60 percent support, according to unofficial results.

Energy from the line is a key part of how Massachusetts plans to achieve its goal of halving emissions by the end of the decade. The Maine vote does not spell the immediate end of the project, as the line’s supporters are already saying they will contest the referendum in court, but even that will likely result in a set-back to the project’s planned timeline—and there is no time to waste.”

The great irony of the situation is New England sits only a few hundred miles from the most prolific natural gas producing region on Earth – the Appalachian Basin. According to the US EIA, if the region were a standalone country it would have been the third largest natural gas producer in the world in the first half of 2021, behind only Russia and the rest of the US. And yet, by refusing to build the necessary pipeline infrastructure, New England has opted out of sharing in this critical domestic bounty. If any thought leaders from the region are reading this piece, the Doomberg team put together this handy guide to solving your regional energy problems:

If New England’s refusal to use natural gas from right next door is ironic, how it sources liquefied natural gas (LNG) is downright perverse, albeit for reasons mostly beyond its control. We’ve written before about how the US has become a substantial player in the LNG market, and how the energy crisis in Europe spread to Asia, causing a bidding war for LNG supply. As luck would have it, New England is a now victim of that bidding war and is facing the prospect of dramatically less LNG supply this winter. How did this happen?

One of the most controversial laws in the US is the Merchant Marine Act of 1920, more commonly known as the Jones Act. The law is meant to help ensure a healthy US merchant marine fleet and to support domestic shipbuilding. These are considered critical to national security, especially during times of war. A key stipulation of the law is that foreign-owned ships cannot transport goods between two US ports – only ships built, owned, and crewed by Americans are permitted to do so.

While the US has become the largest producer of natural gas and an ever-larger exporter of LNG, the country does not produce LNG carriers. Since there are no US LNG carriers, New England cannot benefit from the build-out of LNG export facilities along the Gulf of Mexico, despite having significant LNG import facilities like the one in Everett, Massachusetts. That means New England is in the same bidding pool as Europe and Asia. Amazingly, most LNG imports to the Everett terminal have come from Trinidad and Tobago! Instead of simply building pipelines to its land neighbors, New England pays for boats to sail more than 2,000 miles – burning fossil fuels and polluting the oceans as they do so – and pays a substantially higher price for the privilege. Bonkers!

As we head into the depths of winter, New England is substantially behind in procuring LNG from the international market. Here’s how S&P Global described the situation last week:

“So far this winter season, New England has received just a single cargo at the region's Everett LNG import terminal, which delivered the regasified equivalent of about 2.9 Bcf on Nov. 3. From November to March last season, Everett received seven cargoes carrying 20.5 Bcf. During the 2019-2020 season, the terminal took nine cargoes carrying nearly 23.5 Bcf, Platts Analytics data shows.”

We leave you with a tweet we posted a week ago today that went viral. At the time of this writing, it has been seen by nearly 250,000 people and has over 1,900 likes. With less nuclear, insufficient natural gas pipelines, and no LNG available to save the day, New England is one cold snap away from a substantial disaster. If you live there, prepare your thermal comfort zone accordingly.

If you enjoyed this piece, please do us the HUGE favor of simply clicking the LIKE button!

After 42 years working in the oil & gas industry and having witnessed the booms, busts, shortages, gluts, political responses, demands, promises and the rest; it comes as no surprise to read about the political and bureaucratic missteps in this excellent article. The woke crowd have leveraged their minority to block anything they disagree about and politicians have bent over accordingly to avoid a fight. Yet a fight is coming and when the SHTF, and people die of cold, heads will roll and remediation solutions will be forced through at higher cost and more disruption than if they had been properly planned. We can safely predict that the flock of "grey swans" just down the road, are getting ready to fly our way.

Do you think it's fair to say that Americans (and first-worldians in general) have reached a point where we take infrastructure for granted? Or perhaps that point was reached decades ago... And we think we can do anything, avoid all maintenance, act belligerently and the lights and heat will always work as though that's just the natural state of affairs?

For me I think the question is, how bad will it need to get before there are serious changes? I wonder about this.