Playing Catch Up

The nuclear race goes critical.

“In nuclear war, all men are cremated equal.” – Dexter Gordon

On October 21, Russian President Vladimir Putin announced the successful test of the nuclear-powered Burevestnik cruise missile. The Burevestnik—known to NATO as the SSC-X-9 Skyfall—maintains a range that Russia claims is virtually unlimited. There are no known defenses against the technology. According to the Russian military, the missile was airborne for 15 hours and flew 8,700 miles during the test.

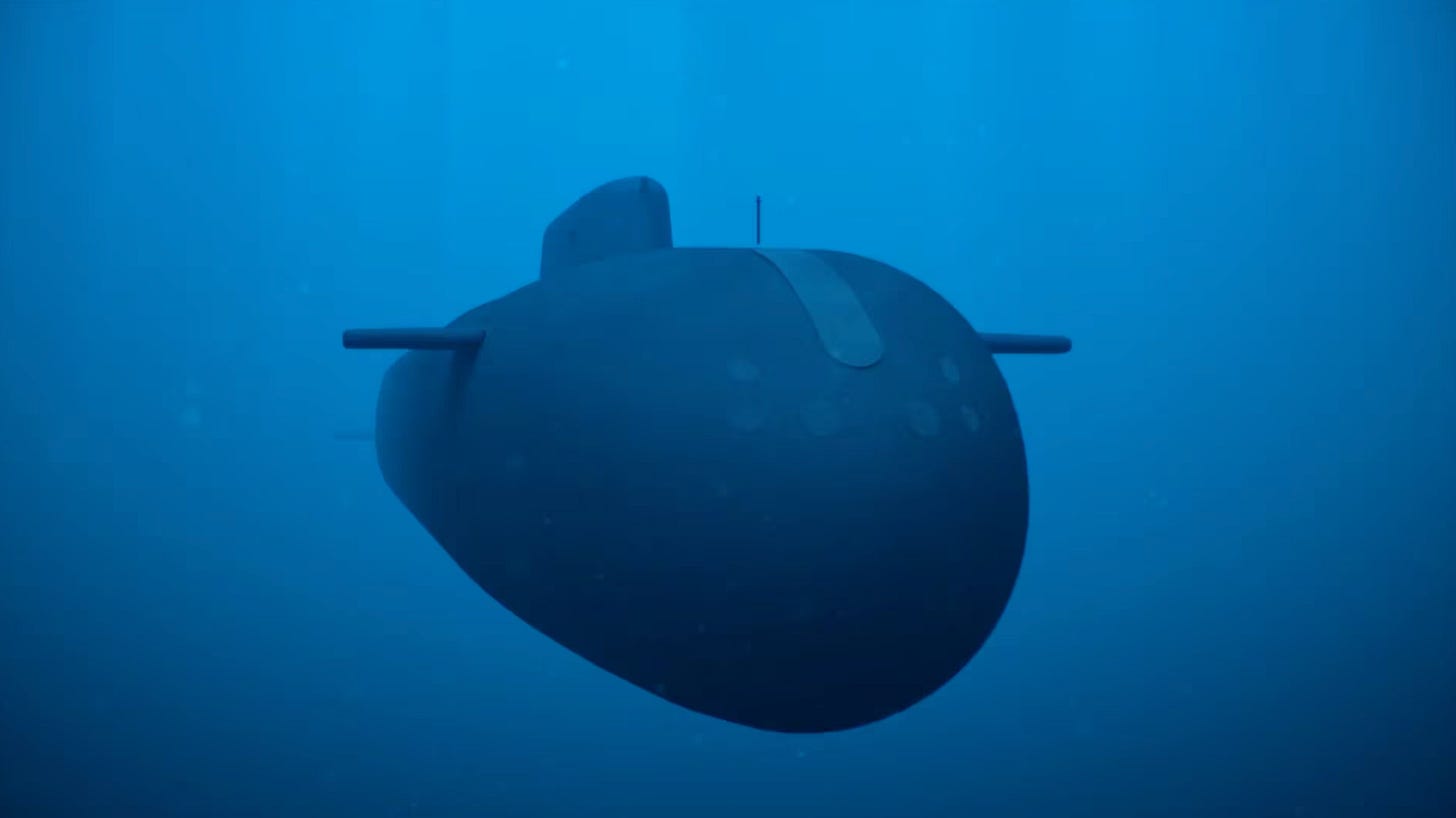

Days later, Putin revealed that Russia had successfully tested the nuclear-powered Poseidon torpedo, a 65-foot-long nuclear death machine capable of triggering massive and radioactive tsunamis toward coastlines all over the world. The Poseidon is allegedly able to operate autonomously at depths and speeds that make interception virtually impossible, assuring Russia of a devastating second-strike ability in the event it is caught off-guard by a preemptive nuclear attack.

Whether you take these military claims at face value, there is no denying that Russia’s civilian nuclear energy sector is world-class. In addition to 36 reactors currently operating within Russia and seven more under construction, government-owned Rosatom has either built or is constructing dozens more in countries around the globe. On the same day that Russia announced the successful Burevestnik test, Rosatom delivered the reactor pressure vessel for the El-Dabaa nuclear power plant in Egypt, marking a major milestone for the high-profile project:

“El Dabaa will be Egypt’s first nuclear power plant, and the first in Africa since South Africa’s Koeberg was built nearly 40 years ago. The Rosatom-led project, about 320 kilometres north-west of Cairo, will comprise four VVER-1200 units, like those already in operation at the Leningrad and Novovoronezh nuclear power plants in Russia, and the Ostrovets plant in Belarus.

Under the 2017 contracts, Rosatom will not only build the plant, but will also supply Russian nuclear fuel for its entire life cycle, including building a storage facility and supplying containers for storing used nuclear fuel. It will also assist Egyptian partners in training personnel and plant maintenance for the first 10 years of its operation. Rosatom said last month that it is aiming for a future service life of 100 years for nuclear power plants.”

Rosatom is also the global leader in uranium enrichment services, holding a 36% worldwide share in that all-important market. The company’s advanced gas centrifuge technology is widely considered best-in-class. Its four major enrichment facilities are anchored by a deep industrial base and decades of operational experience dating back to the Soviet era. In fact, despite the ongoing war in Ukraine and endless sanctions against Russia, Rosatom remains the largest foreign supplier of enriched uranium to the US, providing roughly a fifth of the fuel used to keep America’s fleet of nuclear reactors running. According to the Statistical Review of World Energy, nuclear power accounted for 18% of total US electricity generation in 2024.

In contrast with Rosatom, Canadian-owned Westinghouse—the principal nuclear reactor technology vendor in the US today—has only a handful of its AP1000 reactors under construction, and all are in China, where a modified version of the company’s licensed design (CAP1000) is in use. Plans and promises to build additional AP1000 reactors in Poland, Bulgaria, and Ukraine have been secured, but construction has yet to commence.

Such is the hand US President Donald Trump and his team were dealt upon their return to power, and—to their credit—they seem to recognize the urgency of both the civilian and military nuclear power deficiencies. According to our sources, behind the bluster of Trump’s Truth Social account is a steely resolve to do whatever is necessary to return the US to global preeminence in nuclear power. Will they succeed? Let’s find out.