Political Hamburglars

“The great grafter does not buy government officials after they are elected, as a rule. He owns them beforehand.” - George C. Henderson

Beginning in the fall of 1978 and continuing for a period of 10 months, Hillary Clinton was simultaneously the First Lady of the State of Arkansas, a busy partner in a powerful local law firm, a respected member of various boards, and perhaps the world’s greatest trader of sophisticated cattle futures contracts. Starting with a meager opening deposit of $1,000, Clinton had an incredible knack for catching favorable fills near the highs and/or lows of the day and a savant-like ability to short cattle futures during a raging bull market (pun intended). She parlayed her small stake and good fortune into $99,541 before she cashed out and left the rodeo. This was a handsome sum in 1979 – approximately four times the annual salary she collected as a lawyer.

In a comprehensive and humorous investigation first published by the National Review in early 2015, the mystery of Mrs. Clinton’s seemingly precocious trading abilities is unraveled for all but the most partisan eyes to see. Her “advisor” on these trades was none other than James Blair, whose day job at the time was General Counsel of Tyson Foods, the Arkansas-based meat packing giant with much important business under consideration by then Governor Bill Clinton. The broker who executed her orders was a former Tyson employee with a perfect name, Red Bone – a man who was disciplined by the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) for sloppy record keeping in the same year Mrs. Clinton realized her windfall. As far as schemes to funnel money to powerful politicians go, this episode is notable for its brazenness, but in the pantheon of accusations of corruption that have dogged the Clintons for decades, it is a mostly-forgotten footnote.

If politicians were forced to wear the corporate logos of their deep-pocketed sponsors in the way that golfers and race car drivers do, Tyson’s red and yellow badge would have undoubtedly occupied a prominent place on the Clintons’ golf attire, and almost certainly adorned the prized real estate on the hood of their race car.

The Clintons are hardly unique in this way.

Veterans of the chemical industry used to jokingly refer to the current President as Senator Joseph Biden (D – DuPont). Or consider Robert Caro’s outstanding series of biographies on Lyndon Johnson. In the first of these classics called The Path to Power, Caro lays bare the unseemly role construction and engineering giant Brown & Root played in enabling Johnson’s political career, and the huge amount of government largesse Johnson sent their way in return. Lest the reader think we focus only on Democrats, consider that Brown & Root eventually became a subsidiary of Halliburton, which was presumably thrilled when then-CEO and Chair Dick Cheney ascended to the lofty position of Vice President of the United States in 2000. Plus ça change.

Given the toxicity of the 2008 Democratic primary between Barack Obama and Mrs. Clinton, and the number of former Obama staffers that occupy important positions in the current Biden administration, one could be forgiven for viewing Biden’s recent assault on the meat packing industry through an overtly political lens. Frankly, our initial instinct was to assume the attention from the Oval Office was a combination of political payback, a measure of the ever-falling influence of the Clinton’s over the Democratic Party, and a convenient scapegoat for Biden that could be used to deflect blame for the burst of inflation winding its way through the US economy. Here’s how Biden framed the problem in a recent statement (emphasis added throughout this piece; the big four meat packing companies Biden refers to are the aforementioned Tyson Foods, Cargill, Brazil-based JBS SA, and National Beef Packing Co.):

“Four large meat-packing companies control 85 percent of the beef market. In poultry, the top four processing firms control 54 percent of the market. And in pork, the top four processing firms control about 70 percent of the market. The meatpackers and processors buy from farmers and sell to retailers like grocery stores, making them a key bottleneck in the food supply chain.

When dominant middlemen control so much of the supply chain, they can increase their own profits at the expense of both farmers—who make less—and consumers—who pay more. Most farmers now have little or no choice of buyer for their product and little leverage to negotiate, causing their share of every dollar spent on food to decline. Fifty years ago, ranchers got over 60 cents of every dollar a consumer spent on beef, compared to about 39 cents today. Similarly, hog farmers got 40 to 60 cents on each dollar spent 50 years ago, down to about 19 cents today.”

We reconsidered our initial dismissal of the affair – and decided to cut into the steak ourselves – after coming across an excellent piece on the topic by Matt Stoller, author of the popular Substack BIG. (You can subscribe to Stoller’s Substack here and follow his thoughtful Twitter account here.) Stoller views the growth of monopolistic power in the US as an existential threat to the country and has dedicated his professional career to fighting against it. Stoller tackles the meat packing controversy head on in a blunt article called Economists to Cattle Ranchers: Stop Being So Emotional About the Monopolies Devouring Your Family Businesses.

Stoller begins by noting the growing disparity between the decreasing price paid for cattle and the increasing price paid for wholesale beef, the difference being the growing margins of the meat packers. He then goes on to catalogue how the meat packing market became so concentrated, the impact of consolidation and plant closures on the rancher’s ability to monetize their cattle, and the shift in the way meat packers acquire cattle for slaughter. Stoller’s core accusation is that the big four meat packers have conspired to weaken and then manipulate the cash auctions market for cattle to illegally drive down price. Here’s a key passage:

“Ranchers suspect that the Big Four have been fixing prices to lower what they get paid. This market-rigging took place over time, as the packers gradually forced changes in how cattle markets work. Traditionally, cattle ranchers had sold their cattle at open cash markets where they would display their cows, and packers would bid for them. It was a rich, thick market, with information about prices displayed very clearly to buyers and sellers. Such markets are hard to rig.

But in the mid-2000s, packers began using what are called captive supply deals. Under a captive supply deal, a rancher signs a contract with a packer. He will no longer take his cattle to an open market, but will raise it and sell it to that buyer. Basically, ranchers get a guaranteed sale, while packers get a guaranteed source of cattle. Or that’s the theory. Because there’s still the matter of price. To figure out what the packer should pay, these deals usually just say that the packer has to pay whatever the price is in the normal open cash market…

The cash market, now just 20% of all sales, became what is known as ‘thin,’ meaning there’s a lot less bought and sold. Thin markets are a lot easier to manipulate; a buyer could just pull out of an auction. That doesn’t just lower the price paid in that cash market, but also the cash price for all the captive supply contracts as well.”

For its part, Tyson forcibly rejects accusations of illegal behavior and instead pins the blame for the swoon in cattle prices on unexpected market shocks – especially the Covid-19 pandemic but also a series of severe weather incidents – which led to worker shortages and an inability to process cattle at historical rates. This occurred just as demand for beef in the US and abroad was at record levels, leading to the natural and concurrent outcome of higher prices.

In testimony before Congress, Shane Miller, Group President of Tyson Fresh Meats, argued that the quality, variety, safety, and affordability of meat in the US is proof that the market is working. Here’s Miller driving home that point:

“To be clear, at Tyson, we welcome competition. Healthy competition not only makes us better – it also helps put affordable, higher-quality food on the tables of more Americans.

And the competition is intense. Customers have multiple meat suppliers from which to choose and they subject suppliers to competitive bidding processes based on terms the customers specify. Customers often work with several meat suppliers to ensure orders are filled according to their product specifications, volume requirements, and pricing terms, which adds to the constant pressure to outperform the competition.

Evidence of healthy competition can also be found by looking at historical outcomes. For example, we have seen a rise in availability and quality of beef, while the price has become more affordable over the past quarter-century: data shows that while the concentration of the industry has remained relatively constant for close to 30 years, quality has significantly improved.”

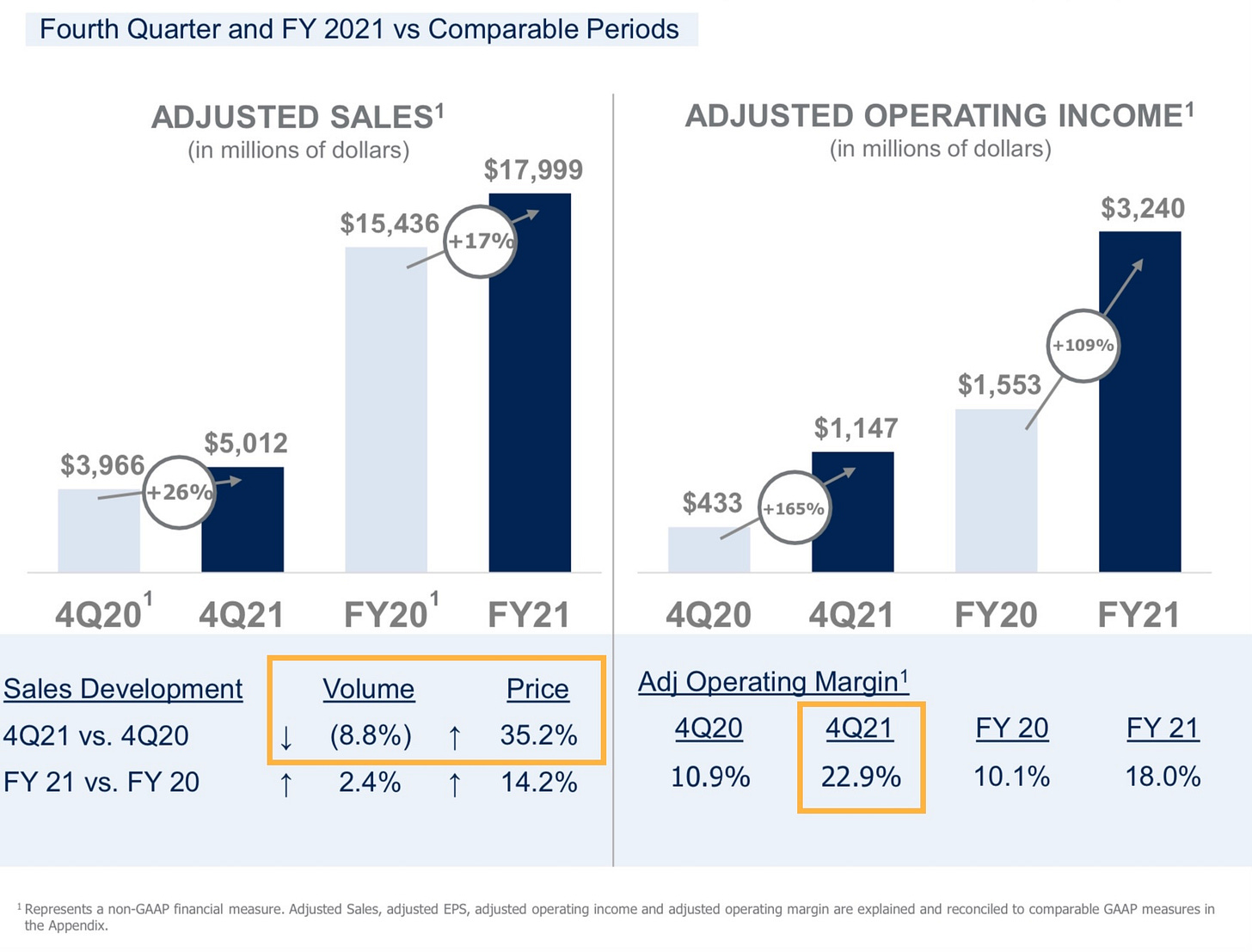

Inspection of Tyson’s latest financial results would seem to lend credibility to Stoller’s argument and undercut Miller’s. Tyson’s 2021 fiscal fourth quarter ended in early October, and the results for their Beef segment are practically sizzling. As shown in the screen capture below, taken from the company’s presentation to investors, Tyson’s Beef segment raised price by an astonishing 35.2% in the quarter versus prior year, which more than compensated for an 8.8% decrease in volume. Additionally, the segment’s operating margin more than doubled to 22.9% of revenue. In the cutthroat food business, such margins are rare indeed.

We interviewed several ranchers and other experts in the agricultural space in the course of our own research – none of whom would go on the record. In some instances, ranchers expressed specific concern about triggering blowback from the big four meat processors – a sign that at least some anticompetitive behavior is indeed occurring. We were able to question ranchers with small and large operations alike and received substantial input from a commodities broker with decades of knowledge and extensive contacts in the industry. Overall, our findings paint a mixed picture.

We begin with the fact that the beef market is global and focusing exclusively on US numbers gives an incomplete view of the overall situation. Certain cuts of beef are regularly imported, while others are exported to meet specific local demand. This is somewhat analogous to how different grades of crude are traded around the world based on unique refinery capabilities. Also, demand for protein is booming overseas, and the larger ranchers with better channel contacts can more easily capitalize on this trend, whereas smaller ranchers are left to fight it out with the big four.

In the past few years, an ongoing and historic drought in Australia forced ranchers with decimated pastures to prematurely liquidate their herds, leading to a temporary burst of supply. While this disruption certainly hasn’t helped US ranchers, the effects should be transient. Here’s a report from late 2019 which described the desperate situation in the Land Down Under:

“Generations of Australia's prime breeding cows are heading to slaughterhouses as a lack of water and feed sees more producers opt to ‘cash in and get out’. Almost 100,000 female cattle have been sold collectively in New South Wales at saleyards in Scone, Singleton, Tamworth, Gunnedah and Dubbo this year alone…

Cattle breeders and agents are concerned about the national herd diminishing and how breeding lines will be rebuilt once the drought breaks.”

Additionally, and with more structural significance, the value chain for cattle has evolved such that ranchers rarely sell directly to meat packers. Instead, there exist specialized operations that acquire cattle in certain weight ranges, bulk them up by a few hundred pounds, and sell them on to the next node in the system. A calf raised by a rancher might be sold to what’s known as a backgrounder, who converts them into feeder cattle. When the desired weight is achieved, the backgrounder then sells their feeder cattle to feed yards, who bring the cattle up to slaughter weight in close collaboration with meat packers, who set detailed specifications for the cattle they’d prefer. Once at weight, the cattle become known colloquially as fat cattle, or more formally as live cattle, which is ironic given what comes next. We’ve drawn this rough value chain in the figure below:

Further, as explained by our broker friend, the CME contracts are essentially hedging instruments without natural buyers, and despite extensive feedback given to the CME by market participants, the contracts no longer serve their intended purpose. Here’s a direct quote:

“The beef industry has been changing over the past 5-10 years. The quality specifications of the cattle that are deliverable against the CME Live Cattle futures contract are no longer the standard for cattle that the packers are demanding, therefore the hedging mechanism doesn't work the way it did in years past.”

This lack of a natural buyer is particularly true for the CME Live Cattle contract, which makes sense when you consider who is taking risks and for how long. The feed yards own cattle for several months and are exposed to all manner of input costs with substantial volatility, whereas the meat packers acquire live cattle just prior to slaughter. When the feed yards hedge, they sell the CME Live Cattle contract, but there’s less urgency for meat packers to get on the other side of their trade. When a market has more sellers than buyers, lower prices usually follow.

Stoller would likely argue that these are all symptoms of the broader disease of too much concentration among the meat packers, and the specific means by which this power manifests itself don’t matter all that much. A credible counterargument is that nearly all markets become more granular, specialized, and concentrated over time, which drives efficiency, lowers costs, and creates better value for end consumers. Larger corporations are more able to navigate these trends, and the crowding out of smaller players as markets mature is a universal and desired feature of the economy – a form of creative destruction.

Starbucks crushed many mom-and-pop coffee shops. Walmart did the same to small department and grocery stores alike. Local hardware stores have been largely replaced by Lowe’s and Home Depot. The response to the pandemic destroyed countless small businesses, much to the advantage of giants like Amazon. One wonders why so much attention is being selectively paid to the plight of the small rancher. The senator most responsible for pushing this issue is Max Baucus of Montana, Biden’s longtime Democratic colleague and ally in the Senate. It wouldn’t surprise us if Baucus sold Biden’s team on the usefulness of this issue as a political deflection point for the inflation challenges facing the administration.

Naturally, Baucus’ family runs the famous Sieben Ranch in Helena, Montana. Plus c'est la même chose.

If you enjoyed this piece, please do us the HUGE favor of simply clicking the LIKE button!

Just a couple of quibbles. Tyson was not in the beef and pork business when Clinton was working for them.

Also- I worked in the industry. The labor shortages are real, and the plants have had a hard time keeping up. I think a lot of immigrants took the checks and went home. I dont blame them as I did the same thing. The labor market is tight in general and it is hard work cutting meat.

Part of me wonders if the packers are enjoying the labor problems as it leads to huge margins for them.

FYI you can track daily beef and pork slaughter numbers here. https://usda.library.cornell.edu/concern/publications/qr46r0849?locale=en

They have been dropping. My guess is due to omicron. I dont watch pork that closely, but beef is usually around 120-123k head/day. In spring of 2020 it was down to around 80k sometimes.

Sometimes plants shut down on a Monday or Friday to clean the coolers, so I would not look at those numbers a representative. One big beef plant shutting down on a Friday will be a 6k reduction in capacity. Tuesday-Thursday is a better number.

I buy beef directly from a local farmer who does the butchering himself. I contact him to find out when he intends to do the next group and I place an order.