Shhh…It’s Only Voluntary

“Diets are a scam.” – Michael Moore

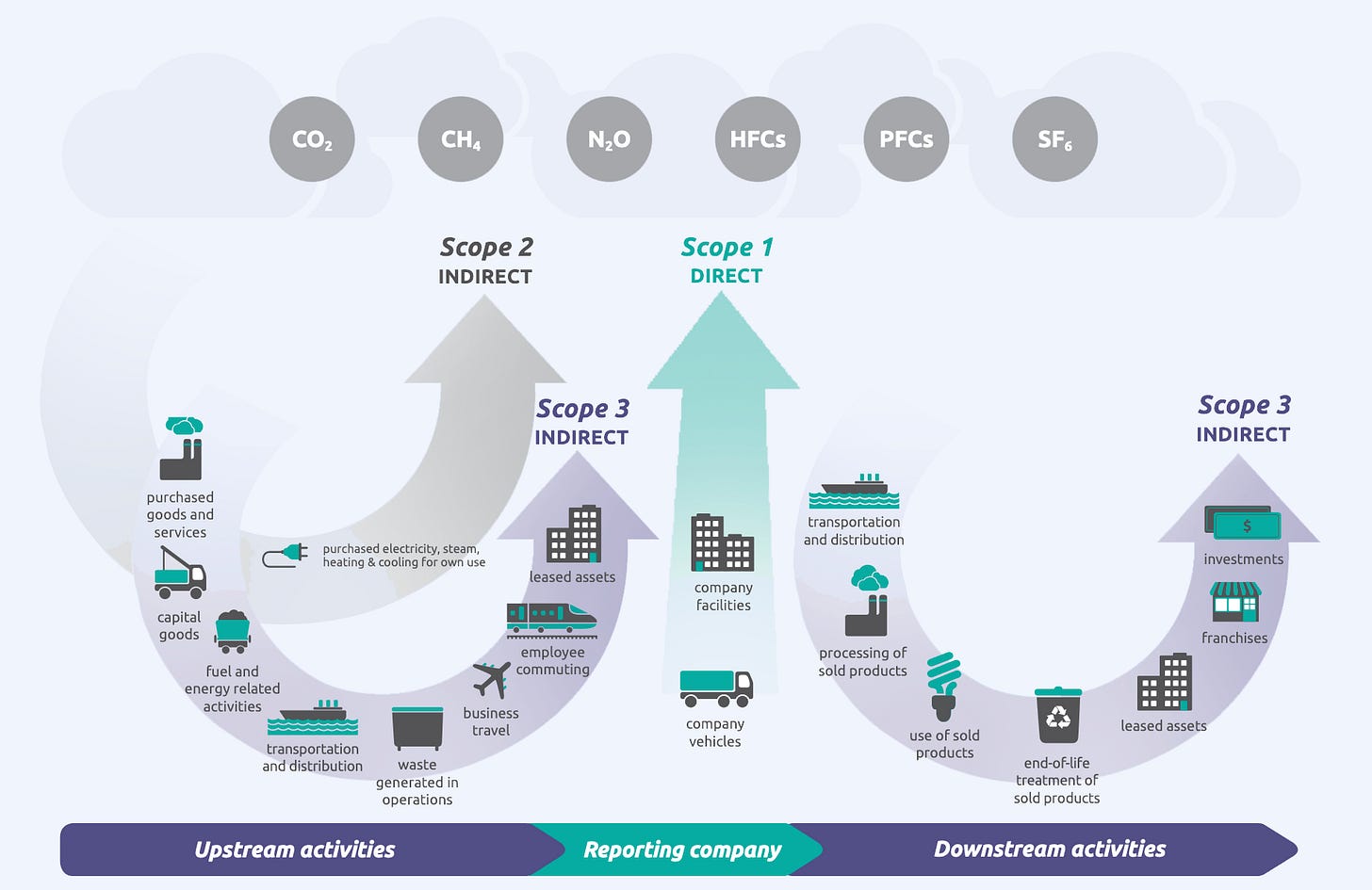

Imagine you are the owner of a small accounting firm in California. Having been drawn into anguished concern over the planet’s climate, you set about the task of learning how your business can do its part to help humanity reset the trajectory of catastrophe. You dutifully head over to the World Economic Forum’s (WEF) website and discover the differences between Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions. There, you learn that Scope 1 emissions are “those that a company causes by operating the things that it owns or controls. These can be a result of running machinery to make products, driving vehicles, or just heating buildings and powering computers.” Since you don’t operate any machinery and get all your power from the grid, you are in pretty good shape there.

Scrolling down the page, you read that Scope 2 emissions “are indirect emissions created by the production of the energy that an organization buys” and that “installing solar panels or sourcing renewable energy rather than using electricity generated using fossil fuels would cut a company’s Scope 2 emissions.” You run a small office with a few computers, a printer, and a coffee maker—Scope 2 certainly seems to apply to your business, and you make a mental note to investigate state and local subsidies that might help you harvest clean power from the sun. No need to carry all the costs of your environmental enlightenment, after all.

Finally, you arrive at Scope 3 emissions, which “are also indirect emissions – meaning those not produced by the company itself – but they differ from Scope 2 as they cover those produced by customers using the company’s products or those produced by suppliers making products that the company uses.” You are in the business of collecting a small vig from people by helping them accurately pay a large vig to the unnecessarily complex bureaucracy known as the Internal Revenue Service—Scope 3 emissions don’t materially apply to you.

A few solar panels it is, then. Done and done.

Now run this scenario as the CEO of a major airline. An airline is literally in the business of combusting huge amounts of jet fuel to move people and cargo across vast distances and there is very little these companies can do to reduce—let alone eliminate—their Scope 1 emissions. (Except to go out of business.) And yet, one by one, the CEOs of these businesses have pledged that their enterprises will achieve “Net Zero by 2050.” The laws of physics dictate that the word “Net” will have to do a helluva lot more work than “Zero” in this regard, as the energy density of jet fuel all but eliminates the practical possibility that battery-powered airplanes will proliferate any time soon. If only there was a vig they could pay to make this problem go away.

As it turns out, there is!

As is often the case when a lot of money is thrown at an impossible task, there are people willing to grab some of it in exchange for claiming to be able to perform magic. For airlines – and other so-called “hard-to-abate” industries – salvation comes as a sleight-of-hand known as “voluntary carbon emission offset credits.” As the name implies, carbon emission offsets are a way for companies to compensate for their greenhouse gas emissions by purchasing credits that allegedly represent the reduction, avoidance, or removal of an equivalent amount of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere somewhere else.

The consulting firm and premiere vig-siphoner McKinsey has taken a keen interest in the voluntary carbon credits market. Named the “knowledge partner” behind the Taskforce on Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets (TSVCM), the firm estimates the market will reach $50 billion by 2030 (up from $2 billion in 2021). The adjective “voluntary” in this rapidly growing segment is used to distinguish it from government-mandated and -supervised carbon credit compliance markets—it is a distinction with a big difference. In theory, voluntary carbon offset programs are meant to support reforestation efforts, energy efficiency initiatives, and other projects that make for splendid pictures in a company’s glossy annual report. The reality should have shareholders up in arms. Fire up the barbecue, our skewers are loaded.