Strait Shooting

Modeling the unthinkable in the oil and gas markets.

“Chaos is the score upon which reality is written.” – Henry Miller

Five months after Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor brought the US into World War II, the American government imposed strict rationing policies on gasoline. Earlier attempts at voluntary action had failed, so civilians were issued ration coupon books, and stickers were placed on vehicles specifying their gasoline allotment. With few exceptions, drivers could use between 2 to 4 gallons per week. A national speed limit of 35 miles per hour—the so-called “Victory Speed”—was implemented, pleasure driving was prohibited, and automobile racing was banned.

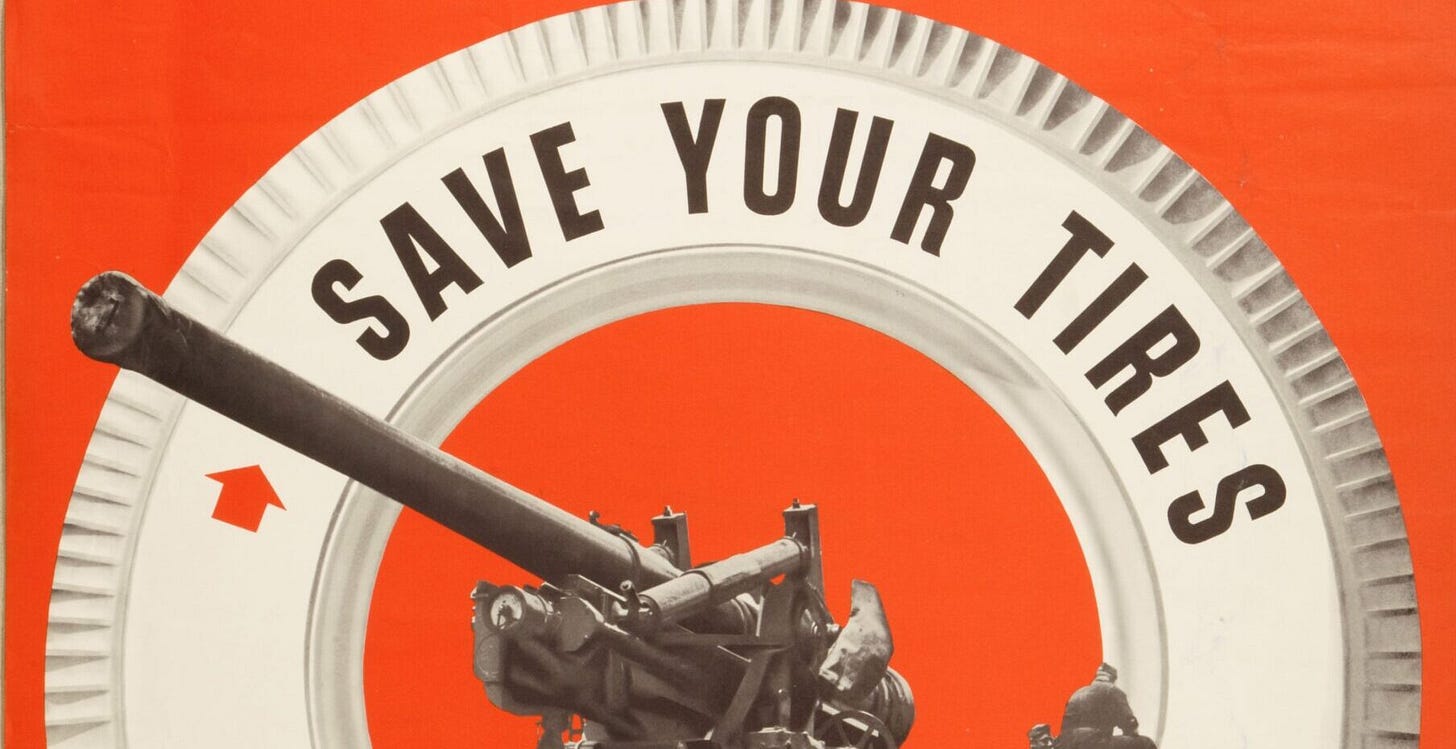

The proximate need for such drastic measures was not a shortage of oil or the gasoline refined from it. The United States was by far the world’s largest producer of both. Rather, it was Japan’s occupation of key rubber-producing regions in Southeast Asia that triggered alarm in Washington. Japanese conquests cut off approximately 90% of the US rubber supply, all of which came from natural sources at the time. Suddenly, civilian use of tires came at the expense of the military, and the most effective way to curb it was by restricting fuel consumption.

The rationing campaign was largely successful, but the initial public panic catalyzed a massive effort by the US government to develop and commercialize synthetic rubber technology. By the end of the war, the country was producing more than 900,000 tons of synthetic rubber per year, a miraculous feat by any measure. The rubber market was permanently transformed, and today roughly half of the world’s rubber production is derived synthetically from oil.

That wars disrupt global trade, cause regional shortages, and spur the development of new technologies that permanently reshape markets is well understood. But predicting the precise consequences of global conflagrations as they unfold is especially challenging. Such is the nature of chaotic systems. Unfortunately, analysts who specialize in energy markets must now take on the task.

As the second major front in what future historians will undoubtedly call World War III exploded into the headlines in recent days, the most pressing question looming over global energy markets is the fate of the Strait of Hormuz. Anxiety over a potential disruption through this all-important chokepoint is well founded: 20 million barrels of oil per day, as well as all of Qatar’s liquefied natural gas (LNG) exports, pass through the narrow channel that connects the Persian Gulf to the Gulf of Oman. Iran has long threatened to close Hormuz in the event of full-scale war, and a complete cessation of flows would undoubtedly trigger a temporary but severe shock to global markets.

While the first-order impacts of a major disruption in Hormuz are relatively straightforward—skyrocketing energy prices, collapsing economic growth, and significant headwinds for global equities—the medium- and long-term consequences are more difficult and, arguably, more interesting to consider. After spending the past week reflecting on the issue, we’ve developed a few counterintuitive conjectures about how events might unfold.