Super Stonks! Uber

“Laws are spider webs through which the big flies pass and the little ones get caught.” – Honore de Balzac

In theory, we are a nation of laws. Laws exist to help organize a more civil and productive society, define the proper manner for how citizens should interact with each other, and set the framework by which government bodies at all levels fund themselves in order to provide public services and goods. Laws are enforced by policing bodies and regulators – often unfairly, to be sure – but overall, the alternative to a society based on laws is usually quite chaotic. We evolved the way we did for sound reasons.

Many people don’t like laws and some don’t consider themselves bound by them. They traverse our society with a touch (or a lot) of narcissism – taking what they like for themselves, consequences be damned. While there’s a formal mechanism to change laws in our society, these people simply ignore the rules that constrain them, daring our policing bodies to do something about it. We usually call such people criminals, but nowadays we sometimes call them startup founders, innovators, and even visionaries.

As described in Sam I Am, arms-length investors (like some venture capitalists) love CEOs that are willing to break laws or, at a minimum, exploit legally questionable loopholes. The risk/reward analysis from the investor perspective is compelling. Breaking laws can be quite lucrative, and if a CEO is willing to do so and can get away with it, there can be an impressive bounty to be split between all parties. To these investors, it’s a heads we win, tails you go to jail situation.

Here’s how it often works. A regulated industry exists at a decent scale. By and large, the incumbent players in that industry follow the rules and compete on a level basis. Somebody invents something that could disrupt that industry, but the current laws prohibit it – and usually for very good reasons. You might think the inventor plays the role of founder in our story, but that’s not always the case. Sometimes, the “founder” is recruited by investors looking to exploit the invention and inserted into the situation specifically because they are willing to ignore the existing laws. Other times, investors inherit a situation like this and properly assess the character of the person in charge. Either way, the founder is given lots of cash and told to run fast and break things – cracking eggs to make omelets, if you will.

The goals are to grow as quickly as possible, at a significantly faster speed than regulators can handle, and to eventually become too big or too popular with consumers to regulate. The behavior of the founder and communication about the company are wrapped in a veneer of innovation but, in reality, there’s a lot of similarities to a RICO operation with expensive lawyers, sleazy lobbyists, and clever public affairs teams playing the role of enabling co-conspirators.

And then there’s Uber. There’s simply no denying that ignoring and violating laws was central to Uber’s culture and business model. In the eyes of Travis Kalanick, Uber’s hard-driving co-founder and former CEO (before he was forced out under the cloud of several scandals), city planners and other regulators were stupid, slow, ignorant about how innovation works, and, most importantly, standing in the way of Kalanick becoming a billionaire. But what separates Uber from other run-of-the-mill Silicon Valley fraudicorns – and what elevates it to Super Stonk status – is the fact that there is no pot of gold at the end of Uber’s ill-gotten rainbow. Uber has ripped the guts of out an entire industry for the right to incinerate cash at an unbelievable (and, at least in the mind of this chicken, unsustainable) rate.

Let’s back up a little. Why would a city want to regulate its taxi industry? One big reason is to ensure that all licensed taxi drivers pass thorough criminal background checks. A city might want to limit the number of taxis in operation to better control traffic flows in and out of its central districts, thereby minimizing traffic jams and encouraging city residents to use public transportation. There may have been environmental considerations. Or a city might have wanted to ensure its taxi drivers weren’t taken advantage of and were given the proper benefits of their labor. The key point is the decision to regulate the taxi industry rested firmly in the hands of each city’s leadership, and an entire industry grew up under these rules, invested capital based on the assumption the rules would persist, and suffered penalties if they dared violate them.

Uber was so brazen in its efforts to circumvent the law that it programmed into its app the ability to avoid picking up any local officials that might be opposed to Uber’s presence in their municipality. Essentially, law enforcement and local politicians had a different app experience than the rest of the public. Called Project Greyball, the scandal was broken by the New York Times in March of 2017. Within months, drowning in a sea of this and other scandals, Kalanick was forced to resign as CEO of Uber.

Beyond the taxi industry itself, Uber has attempted to unilaterally and radically redefine the relationship between labor and capital. As the poster child for the so-called “gig economy,” Uber has fought relentlessly in courtrooms all over the world to avoid having drivers in their network – without whom there would be no Uber – classified as employees. The reason it fights so hard on this issue is simple: if Uber drivers must be treated as employees, Uber’s business collapses. One might not favor labor laws like minimum wage requirements, safety standards, and so on, but these laws – much like regulations that control the taxi industry – nonetheless exist.

What bounty did Uber’s founder and early investors achieve by moving fast and breaking things? In late 2019, shortly after his post-IPO lockup period expired, Kalanick sold all of his Uber stock, netting approximately $2.8 billion in the process. Presumably, early investors in Uber have followed suit. From their perspective, it was mission accomplished – flipping the Uber coin came up heads.

And what is the state-of-the-business as it exists for today’s shareholder? Let’s engage in a little analysis or, as I like to call it, The Stupid Way™ of looking at the value of a stock. It is difficult to measure Uber using traditional price-to-earnings measures, since the company has never made any money. On a more forgiving price-to-sales ratio, and with a market cap approaching $80 billion, the company fetches a healthy multiple of six times revenue. Surely, Uber must be a growth machine, right? Here’s Uber’s quarterly revenue going back 3.5 years:

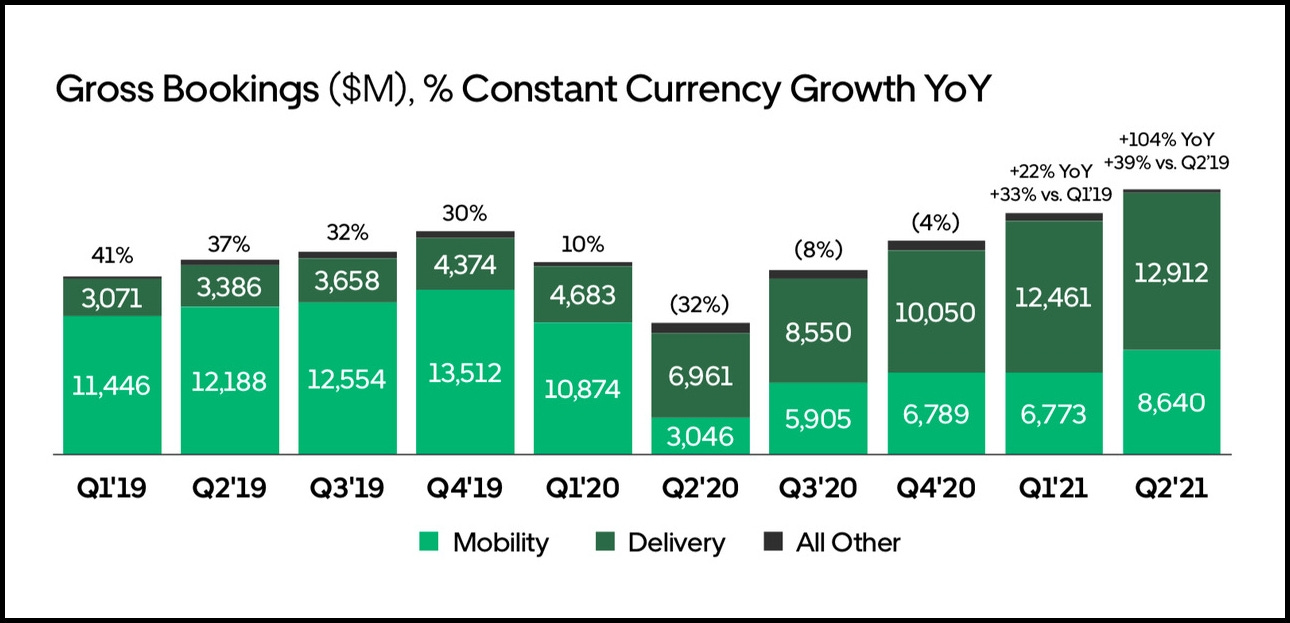

To be fair to Uber, the company was severely impacted by Covid. On the other hand, the company has pivoted away from its traditional mobility business and toward food delivery. Uber acquired Postmates in late 2020 in an all-stock deal and has poured significant resources into making that business grow. One problem with this approach is the food delivery business loses even more money than mobility. It is also deeply competitive, with dozens of upstarts competing for the same share of future business. Digging one level deeper, we see from the company’s most recent quarterly presentation that mobility is a long way from recovering to pre-pandemic levels – assuming it ever does.

What has it cost Uber shareholders to tread water like this? In the past 3.5 years, Uber has evaporated an alarming $11.5 billion in free cash flow. Negative. Gone. Out the door. It is truly a mind-boggling number.

I would be remiss if I didn’t close this piece by commenting on the manner in which Uber presents its financials, something which is a particular pet peeve of mine. As the bull market continues to expand, companies are choosing to present their financials in ways that stretch the truth in an attempt to conjure positive “earnings.” One measure of a company’s “profitability” is EBITDA, which stands for earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization. EBITDA is a silly measure of profitability. It isn’t as though the things excluded from its calculation (i.e., everything that comes after “before”) aren’t real expenses over which management has no control. To the shareholder, they are very real, and good management teams focus on both the top and bottom lines. Managing to the middle of your income statement is dubious at best.

But that’s not nuanced enough for Uber. Uber prefers to present “adjusted EBITDA” and has loudly proclaimed it intends to be breakeven on an adjusted EBITDA basis during the fourth quarter of this year.

Okay.

I’ll leave you with the formal definition of adjusted EBITDA as used by Uber and disclosed in the appendix to their latest presentation on quarterly results. Here it is, in all its glory:

Earnings before: Legal, tax, and regulatory reserve changes and settlements; Goodwill and asset impairments/loss on sale of assets; Restructuring and related charges (credits), net; Gain (loss) on lease arrangement; Acquisition, financing and divestitures related expenses; Accelerated lease costs related to cease-use of ROU assets; COVID-19 response initiatives; Depreciation and amortization; Stock based-compensation expense; Other income (expense), net; Interest expense; Loss from equity method investments; Provision for (benefit from) income taxes; and Net income (loss) attributable to non-controlling interest, net of tax.

If you enjoy Doomberg, subscribe and share a link with your most paranoid friend!

Hi. Another good article by a solid chicken. For more details check out the series of articles Huber Horan has written on Uber. They are on point and provide thoughtful financial detail through the lens of a transportation expert. https://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2021/08/hubert-horan-can-uber-ever-deliver-part-twenty-seven-despite-staggering-losses-the-uber-propaganda-train-keeps-rolling.html

What a crock of shit. No offense, Doomberg is my favorite substack, for which I gladly pay and recommend to anyone who will listen to me, but this is a rare miss. To cast governments as benevolent regulators, gleefully working in the best interest of the people is utter hogwash. Governments are funded by theft and supported by cronies seeking to wield government power to create barriers to entry in order to protect their cartels. Taxi companies were especially guilty of that. In the days before Uber a hack license in NYC cost $1.3 Million PER CAB and the service was garbage. Filthy cabs, high prices, lack of availability, driving like maniacs, and so on. If a government/ big business cartel sets up barriers of entry impossible for innovators to overcome the only reasonable response is war. Regulations be damned. Governments and their cronies be damned. I don't own Uber's stock and never will for the reasons stated above. But thank God for Uber and their flaunting of regulations, because anyone who has spent 10 minutes in Chicago or NYC knows the alternative government protected monopoly was trash.