The New World’s Oil

When it comes to energy, a united Western Hemisphere could neutralize the Middle East.

“Formula for success: rise early, work hard, strike oil.” – J. Paul Getty

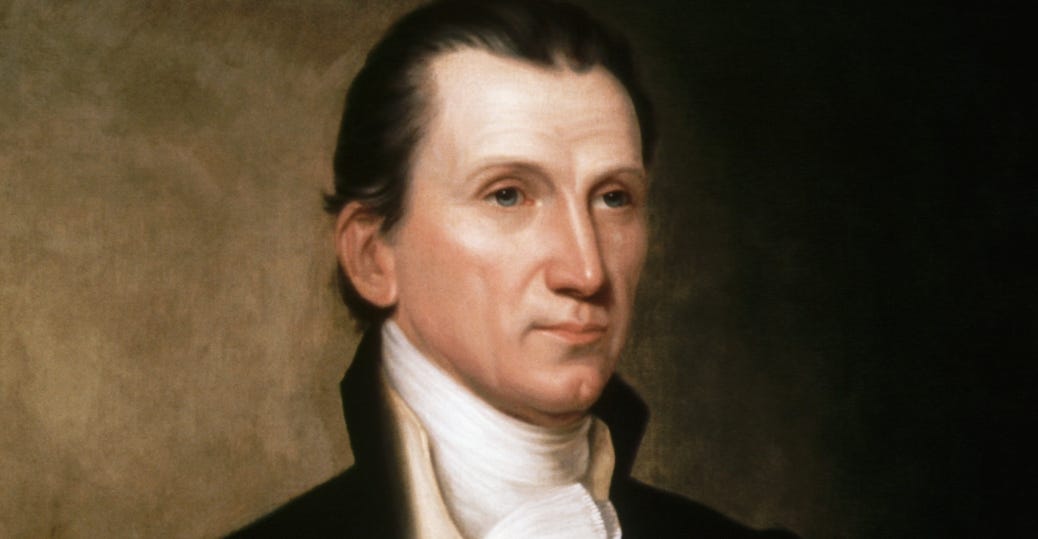

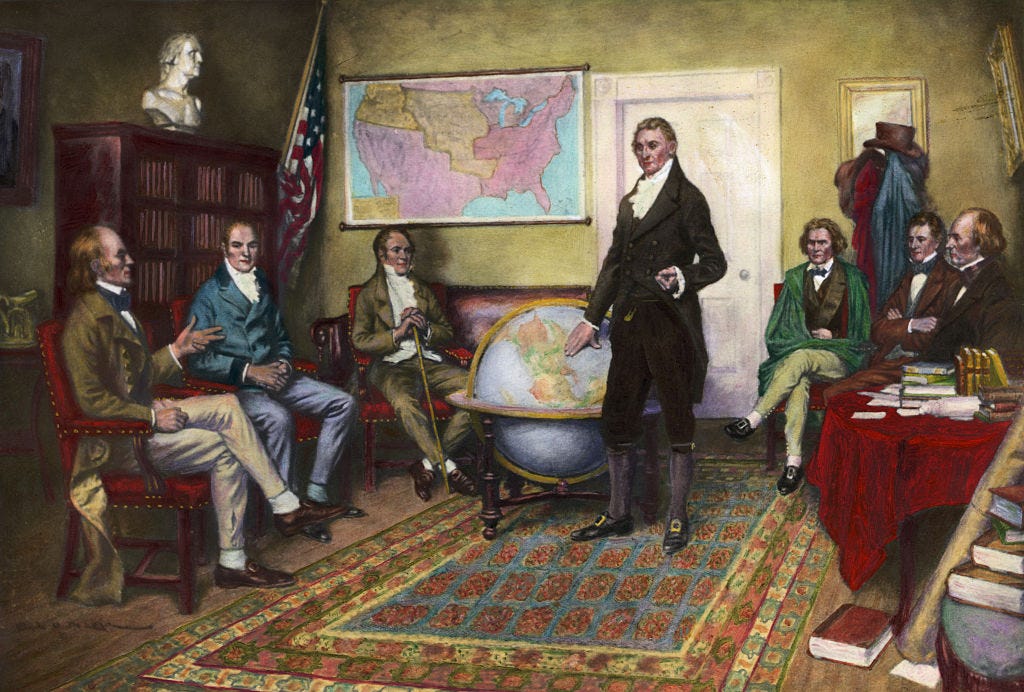

On December 2, 1823, US President James Monroe delivered his seventh annual message to Congress. Unlike today’s spectacles, the early American presidents satisfied their constitutional duty to “give to the Congress Information of the State of the Union, and recommend to their Consideration such measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient” by writing letters at the end of each calendar year. Filled with prose befitting of the esteemed office he held, Monroe’s penultimate address checked in at just under 6,400 words. We found this section rather arresting (emphasis added throughout):

“The actual condition of the public finances more than realizes the favorable anticipations that were entertained of it at the opening of the last session of Congress. On the first of January there was a balance in the Treasury of $4,237,427.55. From that time to the 30th of September the receipts amounted to upward of $16.1M, and the expenditures to $11.4M. During the 4th quarter of the year it is estimated that the receipts will at least equal the expenditures, and that there will remain in the Treasury on the first day of January next a surplus of nearly $9M.”

How things have changed in just two short centuries! With the price of gold fixed at just under $20 an ounce, US federal government expenditures amounted to the equivalent of less than 600,000 ounces of the stuff over the nine months referenced by Monroe. By contrast, today’s sprawling federal bureaucracy spends that much gold in about 100 minutes, churning through the global market cap of all the gold ever mined roughly every two years.

Monroe’s address was not made famous because of the fiscal discipline it described. Rather, it was his articulation of a new, muscular foreign policy that assured this State of the Union a place in the history books. In what became known as the Monroe Doctrine, the President put the European powers on notice that he considered the entire Western Hemisphere to be under America’s sphere of influence. Here is the key passage:

“We owe it, therefore, to candor and to the amicable relations existing between the United States and [European] powers to declare that we should consider any attempt on their part to extend their system to any portion of this hemisphere as dangerous to our peace and safety. With the existing colonies or dependencies of any European power we have not interfered and shall not interfere, but with the Governments who have declared their independence and maintained it, and whose independence we have, on great consideration and on just principles, acknowledged, we could not view any interposition for the purpose of oppressing them, or controlling in any other manner their destiny, by any European power in any other light than as the manifestation of an unfriendly disposition toward the United States.”

As fate would have it, the second centenary of the doctrine’s declaration occurred within days of the passing of its most notorious practitioner, former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. While his death was largely marked with respect in the Western media, we suspect the citizens of Chile, Argentina, and other Latin American countries have a slightly different view of the man, and the ugly events that transpired during and after his tenure in power might explain why China has been able to make such powerful diplomatic inroads in the region in recent decades. That encroachment has inspired talk within the US political establishment of the need to reinvigorate the largely discarded doctrine, but as a recent essay in Foreign Policy makes clear, such efforts are replete with historical and cultural minefields:

“Anticipating renewed great-power rivalry, this time with China, the United States finds itself groping for a coherent approach to challengers from outside the Western Hemisphere—and to challenges from within it. The seeming simplicity and persistence of the Monroe Doctrine mean that it has regained adherents in the United States. Yet recent praise for the doctrine from within the Republican Party suggests only superficial understandings of the doctrine and its meanings in Latin America.

Such uses may be aimed at a domestic U.S. audience, but when they reach Latin American ears, they come off as out of touch—or worse. Praising Monroe won’t persuade Latin Americans that their interests lie in cooperation with the United States rather than its extra-hemispheric rivals. Summoning the doctrine hastens the very outcome it aims to avert.”

Nonetheless, the prospect of a united Western Hemisphere collaborating on a basis of mutual respect does present one particularly compelling prospect: it would create a global energy behemoth. With Venezuela acting in the interests of the OPEC cartel (of which it is a founding member) and Brazil’s stated desire to join it, the prospects of a meaningful alliance on energy between Latin America and the US seem as dim as ever, but that doesn’t mean such a worthy objective should be dismissed. Combining the technical prowess of the major Western oil companies with the huge swaths of undeveloped hydrocarbons south of the equator represents a generational opportunity for wealth creation and strategic advancement for all parties. The numbers are staggering—let’s do a little daydreaming.