The Work of My Life: September 2021 Report

“There is no off position on the genius switch.” – David Letterman

David Berman was a genius in the truest sense of the word; perhaps the best musician you’ve never heard of. I’ve spent more hours than I care to admit listening to his library of work, which began in 1989 when he co-founded the indie rock band Silver Jews. Widely considered by critics to be among the greatest lyricists of his generation, Berman’s raw style and haunting voice earned him a well-deserved cult following among music aficionados.

Berman also struggled with depression, drug addiction, and the financial problems that can arise from both. Like many geniuses, his best work sometimes emerged at his lowest moments. In the two decades that Silver Jews created music together, the band experienced both soaring musical achievements and high turnover – Berman being the band’s only consistent member during their remarkable run. Silver Jews disbanded in early 2009 and Berman largely disappeared from the music scene for a decade, focusing instead on his comparatively fledgling poetry ambitions and his efforts to stay clear of drugs.

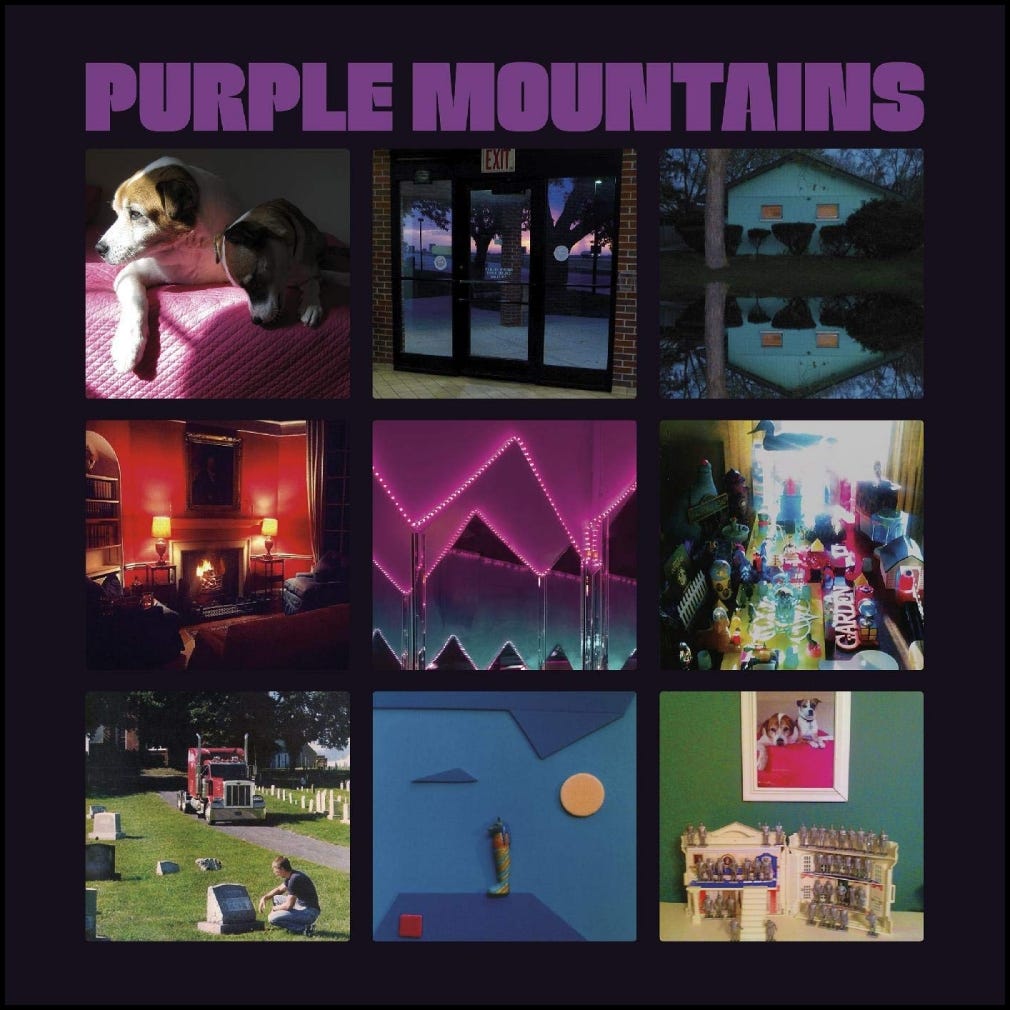

The inspiration for this month’s report arises from Berman’s return to music in July of 2019, when his new band Purple Mountains released their eponymous debut album. Consisting of 10 tracks that run just under 45 minutes, I believe the album is an impressive contribution to the art of music making. The tracks flow from one to another in the way that great albums used to, a skill which I fear has dissipated with the onset of music apps and their stratification of music into isolated quanta of standalone songs optimized for clicks. If the only thing Doomberg inspires you to do is don your best pair of headphones, pour a dark drink, and immerse yourself in the full Purple Mountains experience for three-quarters of an hour, you’re welcome.

Tragically, the album will likely be remembered as a suicide note. Less than a month after the album’s release, and despite the wide critical acclaim it received, Berman hung himself in an apartment in Brooklyn. It’s hard not to listen to the album in that context, especially with the clashing juxtaposition of fast rhythms and cheery beats against shadowed, dark lyrics sung in low tones.

Consider the opening track, That’s Just the Way That I Feel, a song Dick Clark might call “one you could dance to.” Here’s how it begins:

“Well, I don't like talkin' to myself

But someone's gotta say it, hell

I mean, things have not been going well

This time I think I finally fucked myself

You see, the life I live is sickening

I spent a decade playing chicken with oblivion

Day to day, I'm neck and neck with giving in

I'm the same old wreck I've always been”

The beat picks up – literally – with the second track, All My Happiness is Gone, even as the lyrics grow figuratively dimmer:

“Mounting mileage on the dash

Double darkness falling fast

I keep stressing, pressing on

Way deep down at some substratum

Feels like something really wrong has happened

And I confess, I'm barely hanging on”

There’s not much subtlety in the third song, Darkness and Cold, although the fourth – Snow is Falling in Manhattan – is a sweet salve on the rawness of the opening three and presumably pays tribute to some of Berman’s warmer memories from childhood. My favorite song on the album, I Loved Being My Mother’s Son, is a heart wrenching tribute to a lost parent. Left unsaid is Berman’s well-known estrangement from his father, which I suspect was a driving force for many of his struggles (and one that I can relate to). Even within this otherwise gorgeous tribute, I hear hints of what Berman was likely contemplating for after the album was released (emphasis added):

“When she was gone, I was overcome

The simple fact left me stunned

I wasn't done being my mother's son

Only now am I seeing that being's done”

I wasn’t done being my mother’s son. As a parent, can you think of a sweeter thing a child could say about you after your passing?

And then there’s Nights That Won’t Happen. With the harsh context of Berman’s imminent death an inescapable backdrop, the song is almost unlistenable, and yet you can’t turn it off:

“The dead know what they're doing when they leave this world behind

When the here and the hereafter momentarily align

See the need to speed into the lead suddenly declined

The dead know what they're doing when they leave this world behind

And as much as we might like to seize the reel and hit rewind

Or quicken our pursuit of what we're guaranteed to find

When the dying's finally done and the suffering subsides

All the suffering gets done by the ones we leave behind”

It is reported that Berman had a complex relationship with his audience and peers. Constantly hungry for confirmation of his goodness, he felt starved and angry that his art wasn’t more fully appreciated. Here’s how Wikipedia describes it:

“Acutely aware of his public image, Berman feared that after the release of Purple Mountains he would be seen as a ‘sad sack,’ and had earlier wished for his persona to not appear abrasive. He kept note of musicians who had mentioned him in interviews, and believed his music was unappreciated – having ‘always been his own smallest fan.’ He viewed Silver Jews as not a ‘band that other bands would namedrop.’ In music and poetry, Berman felt that his peers saw him as ‘moonlighting.’”

I never met David Berman and so I can’t say whether this is true, but I read his lyrics and see clearly reflected this dark side of the human condition. Like Berman, like many others, I too have struggled with mental health. A key turning point in my life occurred when I trained myself to look inward for acclaim. If you learn to cherish yourself for who you are, what you’ve overcome, and the art you produce – essentially, to accept your own love – you can begin to spin the wheel of despair in the opposite direction.

By no means am I implying this is easy. I have a visceral understanding of just how difficult a bit this is to flip, but if you can pull it off something magical happens. You go from apprehensive about showing your art to excited at the prospect. You stand out from the crowd precisely because you don’t fixate on the crowd. The crowd is there, you acknowledge them, and you humbly accept their endorsement if they are kind enough to give it, but the crowd knows you are going to keep marching either way. The drummer that sets the cadence of your steps resides within you, not out there.

As a parent with two teenage children, I observe how they are bombarded on social media with unattainable expectations and brutal criticisms. It is also the primary means by which they develop friendships, and I suspect it will be core to how work gets done in the decades ahead. In other words, they can’t opt out – and I don’t want them to. I want to help them transform into happy adults who love themselves, who seek fulfillment from within, and who never delegate to others their perceptions of themselves.

I’m not done being my daughter’s father.

In prior editions of The Work of My Life, I’ve openly shared the progress we’ve made by the metrics that matter for judging a content creator’s business – subscribers, followers, and views – and I will do so once again today. But it is important that I state clearly that we interpret these as lagging indicators of our authenticity. We certainly write with the audience in mind, but we are having so much fun with the Doomberg project that we are going to keep on marching even if these numbers dry up.

September was, in many ways, a transformative month for Doomberg. I appeared as a guest on The Grant Williams Podcast, the 10 pieces we published have already averaged 16,000 views each, we crossed 10,000 followers on Twitter, and the number of email subscribers grew by almost a third. Stonky stuff!

Articles published: 49

Total views: 538,569

Email subscribers: 7,344

Twitter followers: 11,073

And with that….headphones on, coffee on the brew, keyboard open.

Ba, da, rum, bum, bum.

Ba, da, rum, bum, bum.

The drummer marches on.

Doomberg, Reading this essay was poignant, difficult and disheartening. The only thing I can say is Thank you. Thank you for teaching me something new with every article. Thank you for making me think in a new and unexpected way. Thank you for allowing me to peer just a tiny bit into your World. But, most of all, Thank you for letting me know that there are still intelligent people on this Planet who aren't giving up, who don't and won't quit and who strive to make the World a better place for everyone... Thank you.

I appreciate this piece because it's the same 'in between' content that provides universal perspective (similar to that Rolex detail that gave you behind the scene insight of supply chains). As for shifting to an internal drum, I share the same outlook as you've described, along with similar estranged father scenario. In fact, just a few weeks ago I've connected to him for the first time and it laid so much to rest. I'm a bit of a financial black sheep in my family, and it turns out he runs money out of Auz! All of this is to say that I greatly appreciate how you tie it all together into great content that reminds people it's not too late to start marching.