Up in Smoke

On the wildfires that are wiping out the balance of carbon emission reductions.

“You can’t come back to something that is gone.” – Richard Powers, The Overstory

In the late 1990s, the mountain pine beetle began its relentless assault on the majestic forests of Western Canada. Using the plentiful host environment of mature lodgepole pine trees, the pests bore into bark, lay their eggs, and spread blue-stain fungi into the vascular systems of their doomed landlords. Choking a tree’s ability to transport water and nutrients, a beetle infestation usually leads to death within a year. Vast swaths of forest have since been laid to waste in the region and massive amounts of dried fuel remain, just a spark away from an inferno.

Exposure to such peril has been the source of persistent controversy, especially in and around the historic small towns along the border of British Columbia and Alberta. Prescribed burns, selective harvesting, and even chemical treatment are known to slow the beetle’s spread and reduce the risk of fires, but such techniques are often opposed by environmentalists. The tourist town of Jasper, Alberta, fell victim to its looming disaster in late July:

“A fast-moving wildfire in the Canadian Rockies that had prompted 25,000 people to flee roared into the near-deserted town of Jasper overnight with flames higher than treetops, devastating up to half of its structures, officials said Thursday.

There were no immediate reports of injuries, following a mass evacuation of the picturesque resort and a neighboring national park earlier in the week, but Jasper Mayor Richard Ireland said in a letter on the town’s website that the wildfire ‘ravaged our beloved community.’

‘The destruction and loss that many you are facing and feeling is beyond description and comprehension, my deepest sympathies go out to each of you,’ he said.”

A predictable set of recriminations followed the tragedy, with environmentalists blaming climate change for both the beetle invasion and the drought conditions that facilitated the fire. Critics argue that Parks Canada—the federal bureaucracy accountable for managing Jasper National Park and similar conservation areas across the country—had largely ignored decades of warnings about the tinderbox its hands-off policies had left in place and that it had failed to coordinate with provincial officials far more experienced at fighting such fires. The CEO of Parks Canada, Ron Hallman, has forcibly rejected such criticism, with supporters claiming that because only part of Jasper was razed, the episode should be viewed as a “success.” Canada’s notoriously progressive Minister of Environment and Climate Change and former member of Greenpeace, Steven Guilbeault, has defended his role at every opportunity, claiming “no request went unmet” as the fire spread.

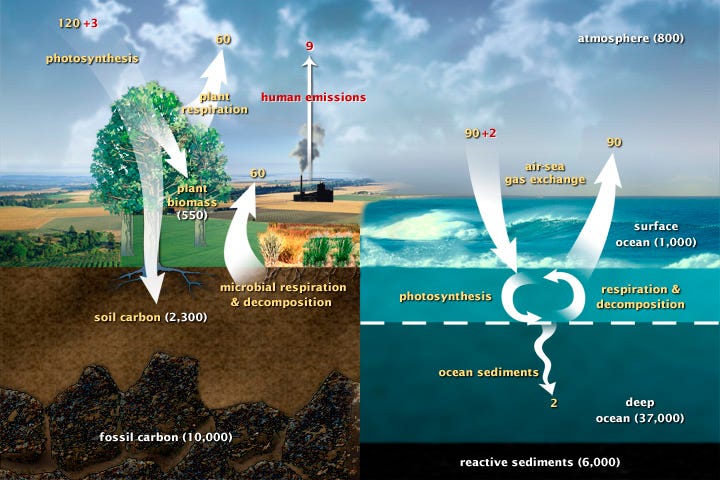

For those who claim to be concerned about carbon emissions, managing forests to optimize sequestered carbon seems an obvious priority, especially in light of the magnitudes involved. As we have previously written: “Total [annual] human emissions amount to 9 billion tons of carbon (~36 billion tons of CO2). Of this amount, 3 billion tons are being absorbed by excess plant photosynthesis and 2 billion tons are being dissolved in the earth’s oceans, a phenomenon that is blamed for the observed acidification of these important bodies of water. The remaining 4 billion tons are accumulating in the atmosphere. Although one wonders how such numbers are measured with any semblance of precision, for the purpose of this article, we take them at face value.” To ignore sound measures that prevent or limit the scope of forest fires is to undo years of accumulated carbon sequestration.

The issue need not be confined to the Canadian frontier. The state of California has suffered from a combination of arson, electricity-grid management scandals, and resistance to proactive forest management that has led to one catastrophe after another. The state keeps copious statistics on all things climate, including estimated emissions from each forest fire within its borders. Inspecting the last two decade’s worth of data reveals a story steeped in irony so pronounced it would be humorous if it weren’t deadly serious.