Wishcasting

But muh peak cheap oil?

“Beware of false knowledge; it is more dangerous than ignorance.” – Mark Twain

In the aftermath of the 1973 oil embargo, the collective West took significant action to insulate itself from future supply disruptions. One product of the response was the International Energy Agency (IEA), an autonomous group within the framework of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Formed in 1974, the IEA’s primary mission was to promote energy security among its member countries and foster international cooperation in energy policy. Over the ensuing decades, the IEA also became known as a non-partial, credible source of contemporary energy statistics and forecasted trends in supply and demand around the globe.

Things started to take a noticeable shift when Turkish economist Fatih Birol ascended to the position of Executive Director of the IEA in 2015. Holding what is intended to be an energy-neutral role, Birol has been criticized for his overt support of renewable energy and his advocacy of a complete cessation of capital investment in traditional energy sources like coal, oil, and natural gas, openly stating in 2021 that “there is no need for investment in new fossil fuel supply.” Concurrent with this pronounced shift to partiality is a decline in the IEA’s reputation for data quality among the global energy analysts who had previously relied on it.

Things came to an unusually public head shortly after war broke out in Ukraine when the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) formally severed data ties with the IEA, issuing a decidedly blunt press release announcing the move:

“OPEC Secretary General, Haitham Al Ghais said: ‘It is ironic that the IEA, an agency that has repeatedly shifted its narratives and forecasts on a regular basis in recent years, now addresses the oil and gas industry and says that this is a ‘moment of truth’. The manner in which the IEA has unfortunately used its social media platforms in recent days to criticize and instruct the oil and gas industry is undiplomatic to say the least. OPEC itself is not an organization that would prescribe to others what they should do.’

OPEC also believes that the proposed IEA ‘Framework to assess the alignment of company targets with the NZE Scenario’ is a tool intended to curtail the sovereign actions and choices of oil and gas producing developing countries, through pressurizing their National Oil Companies.”

Last week, the IEA issued its official 2030 oil forecast, triggering a tsunami of anxious headlines. An article in the Financial Times titled “World faces ‘staggering’ oil glut by end of decade, energy watchdog warns” contributed its bit:

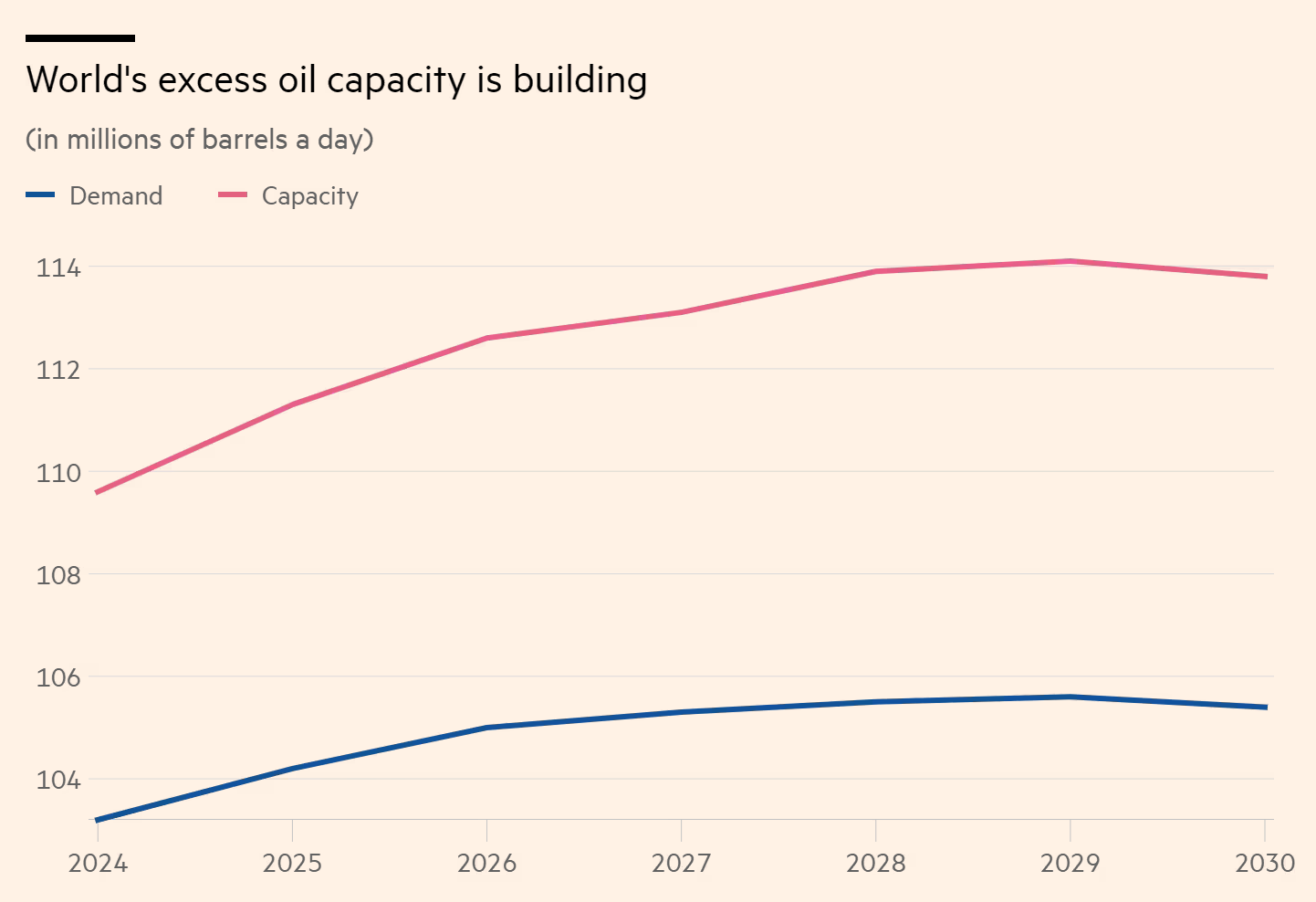

“The world faces a ‘staggering’ surplus of oil equating to millions of barrels a day by the end of the decade, as oil companies increase production, undermining the ability of Opec+ to manage crude prices, the International Energy Agency has warned.

While demand is forecast to peak before 2030, continued investment by oil producers, led by the US, would by then result in more than 8mn b/d of spare capacity, the IEA wrote in its annual report on the industry released on Wednesday.”

According to the IEA, the forecasted surplus is driven by decreased demand for oil products as electric vehicles and other green technologies gain market share. In the accompanying press release, Birol warns that “oil companies may want to make sure their business strategies and plans are prepared for the changes taking place”—a plain reiteration of his 2021 call to drastically slow incremental investments.

What are we to make of this missive? Are we truly headed for a terminal glut in the oil markets? In our view, the IEA is partially correct but for the wrong reasons. Absent a major geopolitical catastrophe, the oil markets look set for an extended period of ample supply. However, demand isn’t going to peak anytime soon. Let’s find out why.