As the Pieces Lie

Early thoughts on how to play energy in a post-OPEC world.

“We live in a fantasy world, a world of illusion. The great task in life is to find reality.” – Iris Murdoch

Although history remembers Marion King Hubbert for his disastrously wrong peak oil theory, it was actually only his second-worst idea. Hubbert was also a founder of the technocracy movement, which advocated governance by technical experts under the belief that scientists and engineers would be better resource allocators than politicians or free markets. Having lived through shifts as drastic as the Covid-19 response and as trivial as the self-checkout overhaul across retail interactions, anyone with a pulse during the last five years can probably attest to what a rotten kettle of fish that vision, if fully implemented, would turn out to be.

While the dystopian concept of technocracy has mostly been discarded into the bin of deeply flawed ideas, Hubbert’s peak oil concept has proved more difficult to shake—much to the detriment of many energy investors. Its stickiness is surely a consequence of its seductive simplicity: There is a finite amount of oil in the ground, we seem to be burning a lot of it, and if we keep this up, supplies will have to dry up. Besides, who doesn’t like a good bull thesis?

The flaws of Hubbert’s pessimism lie in sleights of hand regarding timing, technology, and scale—concepts best illustrated through distinguishing the terms “resource” and “reserve.” In the context of hydrocarbon markets, a resource refers to the total estimated quantity of oil, gas, or coal within a deposit’s geological boundaries, regardless of whether it can ever be exploited. A reserve, by contrast, is a resource against which sufficient investment has been made to demonstrate both technological and economic viability. Many viable resources never become reserves, and only a small fraction of reserves is in production at any given time.

The sheer size of the world’s hydrocarbon resources, combined with humanity’s ever-advancing technological capabilities, ensures that price spikes are answered with ample new supply over time. The higher the price, the higher the motivation to innovate, the more viable all resources become, and the more likely proved reserves are put into production.

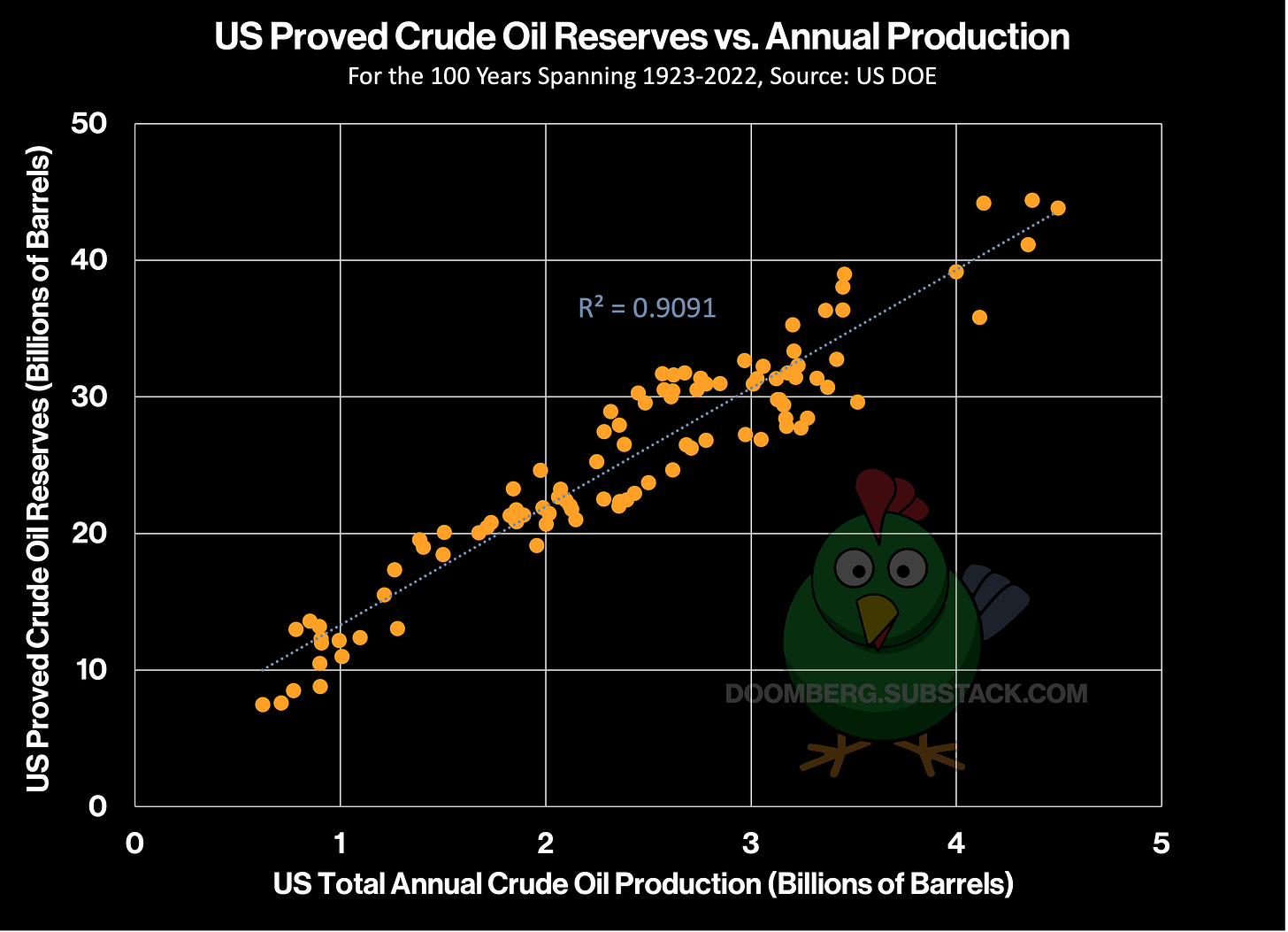

Consider the relationship between US crude oil production and the country’s inventory of proved reserves. The US entered 2022—the most recent year for which full data is available from the US Energy Information Administration (EIA)—with 44.4 billion barrels of crude oil reserves. It produced 4.37 billion barrels of crude during the calendar year, yet exited 2022 with 48.3 billion barrels in reserve. This data comes as no surprise to us, as the US has been producing roughly one-tenth of its proved reserves for over a century. The correlation is striking:

One would hope that last week’s concession from the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) that it can no longer manipulate crude oil prices higher might finally put an end to the peak oil prattle. As described in our most recent missive, we view OPEC’s surrender as a seminal moment in the energy markets—one that will reverberate for years to come. Having now had a few more days to process the news, we return to speculate on its broader implications, including a few non-obvious winners and losers. If we’re right, opportunities abound for shrewd investors on both the long and the short side of the ledger.