Buy Me a River

“Any party which takes credit for the rain must not be surprised if its opponents blame it for the drought.” – Dwight Morrow

The Russian invasion of Ukraine and the recent moves in and around the Arctic Circle have caused us, like so many others, to become reacquainted with the work of Peter Zeihan. Zeihan is a prolific author, strategic thinker, geopolitical consultant, and content creator whose views are as well researched as they are strongly held. His book Disunited Nations: The Scramble for Power in an Ungoverned World is particularly prescient, and the fourth chapter of the book – How to Be a Successful Country – is a useful framework for geopolitical study. According to Zeihan, a country’s territorial viability, agricultural capacity, demographic structure, and energy access dictate its relative standing on the international stage. Countless wars have been fought seeking to augment strengths and plug weaknesses along these parameters.

The first factor Zeihan defines as foundational to a country’s inherent strength is its internal natural water system, and few countries are as blessed as the US in this regard. Rivers represent cheap transportation, reliable irrigation for farming, critical fresh water for drinking, and a ready source of renewable electricity. The mighty Mississippi River – and its direct access to some of the most prolific agricultural plains in the world – gives the US an incredible geopolitical advantage. Here’s how Zeihan describes it (emphasis added throughout):

“But America’s Midwest is a place apart: The Greater Mississippi system includes over thirteen thousand miles of naturally navigable, interconnected waterways—more than the combined total of all the world’s non-American internal river systems—and it almost perfectly overlaps the largest contiguous piece of arable, flat, temperate-zone land under a single political authority in the world.”

Inspection of a US river map calibrated for water flow – like the one shown below – is revealing. Two things leap out right away. First, the Greater Mississippi system is truly huge. Second, if we apply Zeihan’s framework to regions within the country, it is obvious that the vastly populated Southwest is overdependent on the flows of the Colorado River. Given the dwindling volumes ushered through this critical channel in recent decades, this reliance is a vulnerability made only worse by the substantial self-interest and political wranglings arresting any alternatives for the region.

The Colorado River stretches 1,450 miles from the Rocky Mountains towards the Gulf of California (it now runs dry before getting there in most years). It is fed by a large river basin that sprawls over seven states, but the primary driver of water flow is the annual snowmelt in the Rockies. With 15 dams on the main stem of the river and a dizzying array of canals, the water from the Colorado River is likely the most controversial and heavily litigated on the planet – literally every drop is fought after and accounted for. Each action upstream impacts the people downstream, and the allocation decisions are made using agreements that were struck as long as a century ago. Here’s how the US Department of Interior describes it:

“The Colorado River is managed and operated under numerous compacts, federal laws, court decisions and decrees, contracts, and regulatory guidelines collectively known as the ‘Law of the River.’ This collection of documents apportions the water and regulates the use and management of the Colorado River among the seven basin states and Mexico.”

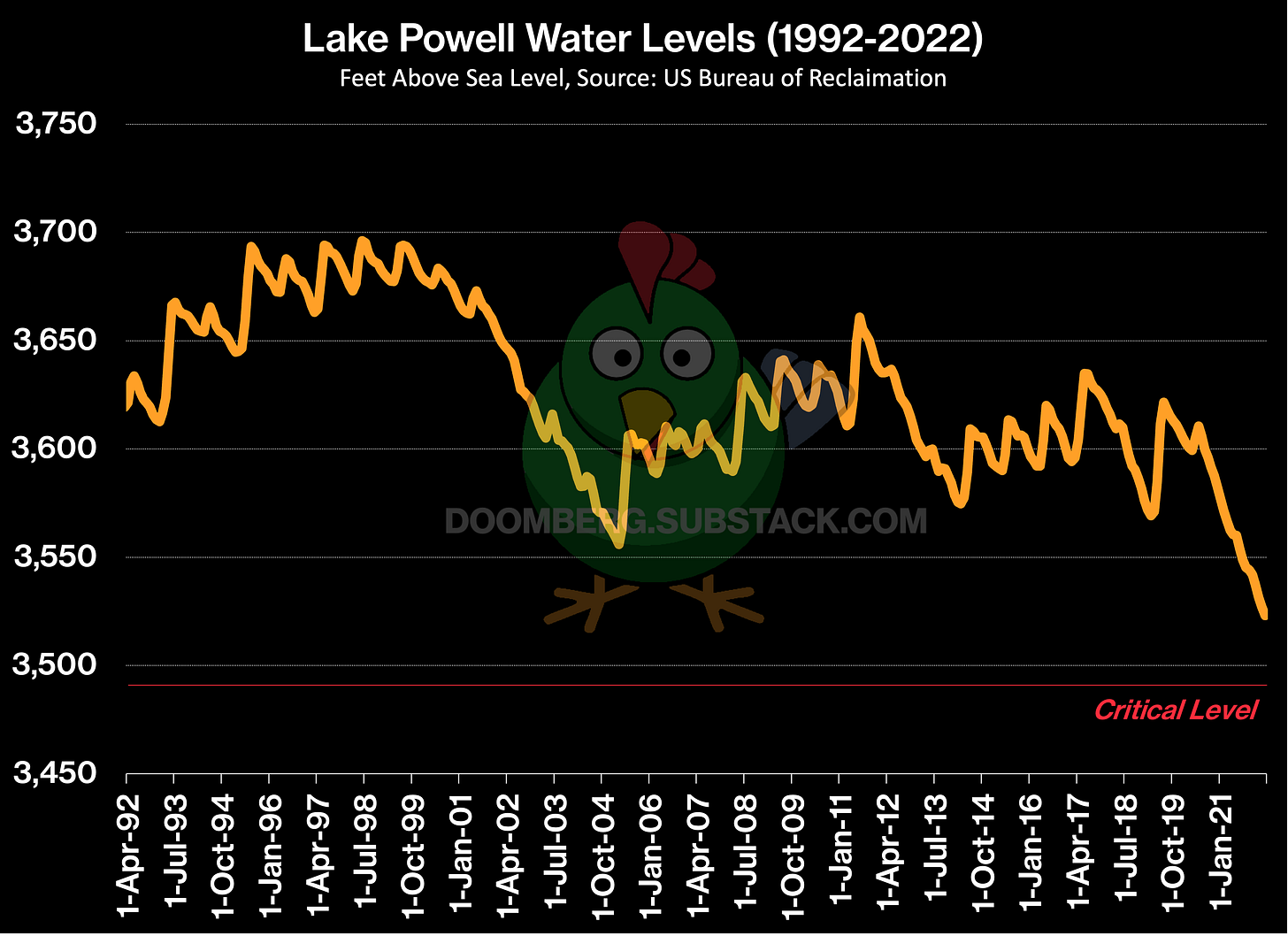

The US Southwest is in year 22 of a historic megadrought, which a recent study estimates is the region’s driest stretch in the past 1,200 years. This has strained the annual supply from the Colorado River’s many tributaries and heightened awareness and scrutiny of its use. The two largest dams on the river – the Glen Canyon Dam at Lake Powell and the Hoover Dam at Lake Mead – are essential to their respective local power grids. They also supply hard, numerical insight into how strained the water levels have become, with expectations at Lake Powell reaching crisis stage:

“Insufficient runoff has put the reservoir on a quick and dangerous descent to 3,490 feet of elevation – a water level so low that Glen Canyon Dam’s hydropower turbines can no longer operate. A key part of the Western power grid would be lost.

The city of Page and the LeChee Chapter of the Navajo Nation also would lose their drinking water because the infrastructure that supplies them could no longer function.

Not to mention that if Powell falls to 3,490 feet, the only way millions of acre-feet of Colorado River water can flow past the dam and downstream to sustain Lake Mead – the reservoir on which Arizona relies – is through four bypass tubes, which have never handled that kind of volume, particularly for an extended period.”

To address its deepening concern over Lake Powell, the government is contemplating taking the drastic action of cutting the volume of water released for other uses:

“In an effort to protect the infrastructure at Lake Powell and the ability of Glen Canyon Dam to generate electricity, the U.S. Department of the Interior may keep nearly a half million acre-feet of water in the Utah reservoir instead of releasing that water to the Lower Basin states of Arizona, California and Nevada this year as scheduled.”

As with our previous piece on natural gas, unfamiliar units of measure like “acre-feet” make framing the scale of the crisis challenging for the general reader. Here, an acre-foot is – as one might expect – the volume of water needed to fill an area the size of an acre with 12 inches of water, and its origin can be traced back to measuring how much water a farmer typically needs per acre planted to achieve a successful harvest. The cuts being contemplated at Lake Powell represent approximately 6.5% of the total annual release from that facility of 7.5 million acre-feet. Without alternative sources available, those cuts will be felt downstream.

A core issue with “public goods” like water and electricity is the lack of a real-time pricing signal to optimize allocation. The Colorado River is an extreme example of what happens when price is suppressed and allocations are determined by politics. In essence, the fight over its water is a fight for a government handout, because the true value of that water is far higher than the price being paid for it by the recipients. Ironically, as shortages emerge, the value of that handout increases, causing demand for it to increase in kind – the exact opposite of how a free market would typically operate. Such circumstances often result in bizarre outcomes and nowhere is this more evident than in the Imperial Valley of California, one of the biggest beneficiaries of the current Colorado River hierarchy.

Imperial Valley is situated near the end of the Colorado River, just north of the California-Mexico border. Despite being the last stop on the US part of the line, California has the highest seniority claims on the river’s flow and is allocated some 4.4 million acre-feet per year, most of which gets directed to the roughly 200 landowners in the Imperial Valley. Put simply, this is a powerful group of landowners. Here’s how the Los Angeles Times framed the situation in a recent article (the entire article is worth the read for a sense of the raw political power at the center of this issue):

“In terms of water, the valley is especially important because the Imperial Irrigation District holds a right to an astounding 3.1 million acre-feet of the Colorado River’s annual flow. That’s roughly 20% of all the river’s water allocated across seven western states. It’s about two-thirds of California’s stake in the Colorado, and as much as Arizona and Nevada receive combined.”

Leveraging this government-secured bounty, Imperial Valley has been transformed from an inhospitable desert into some of the most prolific farmland in the US. The region is farmed year-round and is a major source of winter fruits and vegetables. It has never been shorted its allocation from the Colorado River (although it was forced to sell some water to the San Diego Water Authority in 2003), and a quick inspection of the region using Google Earth makes for a stunning picture:

The broad, looming crisis of the Colorado River’s dwindling volume is giving way to immediate, time-sensitive flare-ups. Lake Powell’s inability to ensure smooth operation at the Glen Canyon Powerplant is the most recent one, and its proposed cutbacks will simply generate flare-ups elsewhere down the line.

How might this otherwise be solved? We begin by sizing the problem. A simple Google search reveals that Glen Canyon produces 5,000 gigawatt-hours of electricity per year, whereas the plant at the Hoover Dam delivers 4,000 gigawatt-hours per year. To benchmark, we recall a piece we wrote in December, California Ditzkrieg, in which we chronicled California doing its best Germany impersonation: the one remaining nuclear power plant in the state – Diablo Canyon – is scheduled for closure in a few years. How much electricity does Diablo Canyon produce? 18,000 gigawatt-hours. In other words, the last remaining nuclear power plant in California produces twice as much electricity as the two biggest dams on the Colorado River.

As we often say, “Go Nuclear!”

While replacing the electricity generated by the Colorado River is straightforward enough, the substitution of its irrigation and drinking water uses would, most certainly, be more challenging. For scale, we turn to the largest existing desalination plant in California. In an irony not lost on us, the Carlsbad Desalination Plant is situated near San Diego, less than 100 miles from Imperial Valley. The plant produces 56,000 acre-feet of clean water per year, which means a total of nine such facilities could offset the proposed 2022 allocation cuts from the Colorado River. How feasible is this? No new technology is needed to deploy a fleet of reverse osmosis (RO) water factories where they are most needed – this challenge is largely a political one.

The company that operates Carlsbad – Poseidon Water – has been proposing to build a similar facility in Huntington Beach, which is just an hour north of San Diego. The plant is estimated to cost $1.4 billion to complete. Despite strong support from the Governor and his allies, the project remains mired in the typical red tape that all too often inhibit sensible infrastructure projects:

“The controversial Poseidon desalination plant has been in the works for more than 20 years and one of the final steps in the process, a meeting regarding a coastal development permit, has been delayed till later this spring. The meeting was set for March 17 for the proposed facility, which will be located at 21730 Newland St., near the AES power plant in Huntington Beach.

‘In order to accommodate the California Coastal Commission’s staff and their diligent review of our application, Poseidon Water made the decision to voluntarily delay the hearing on the Coastal Development Permit until later this spring,’ said Poseidon Director of Communications Jessica Jones. ‘We’re proud of how thoroughly this project has been studied through engineering and technical reports and over-mitigated in order to protect the surrounding environment. The decision to delay the hearing will give staff the time they need to evaluate all of the materials submitted into the record.’”

Twenty years just wasn’t enough.

Ultimately, energy is life, and the water that flows from the Rockies through the heart of the Southwest is the literal embodiment of stored, life-giving energy. How and where we exploit energy sources are choices, and all choices come with tradeoffs.

Alas, we live in a hyperpolitical world, and we are led by politicians with misaligned incentives, dubious ethics, and scant knowledge of physics. As is often the case in such circumstances, we are left with nothing but a menu of bad choices to paper over the problems of the past, and costly tradeoffs not borne by those who force them.

If you enjoyed this piece, please hit the “Like” button and consider securing your spot in the Chicken Coop. New articles go behind a paywall after April 30th – subscribe today!

It's the Putin drought.

Nothing gets solved until it's a crisis and usually it's too late. We then look back and wonder why we didn't do something sooner. Great post!