Measure Twice: Sizing Europe’s Natural Gas Crisis

“It's clearly a budget. It's got a lot of numbers in it.” – George W. Bush

Numbers can be confusing, but numbers without proper context can be downright befuddling. In measuring anything, the unit of measurement is as important as the number itself – units are meant to anchor the mind to a useful reference point. As a measure of time, for example, “score” doesn’t mean much until one performs the mental trick of converting scores into years (there are 20 years in a score), and only then does Abraham Lincoln’s famous phrase “four score and seven years ago” make sense.

To the unscrupulous marketer, selecting the unit of measurement can be an opportunity to manipulate. A small radio station might brag about “50,000 milliwatts of power,” or an environmental group might warn about “300 parts per billion” of a contaminate in the soil, the former sounding more impressive than 50 watts and the latter more ominous than 0.3 parts per million. A classic example of such can be spotted in the reporting done on oil spills. The universal unit of measure for oil is a barrel, but there are 42 gallons in a barrel of oil, and 42 is a much bigger number than 1. Guess which unit is almost always used in reporting on spills? We’re certainly not here to minimize such accidents, but notice how History.com describes the famous Exxon Valdez disaster (emphasis added throughout):

“The Exxon Valdez oil spill was a manmade disaster that occurred when Exxon Valdez, an oil tanker owned by the Exxon Shipping Company, spilled 11 million gallons of crude oil into Alaska’s Prince William Sound on March 24, 1989.”

Confusion is amplified when there isn’t a universal unit of measure, and no commodity suffers more from a bewildering array of seemingly disconnected measurement units than natural gas. The price of natural gas in the US is quoted in dollars per million British thermal units (BTU). In Europe, it is priced in Euros per megawatt-hour (MWh). Production might be quoted as billion cubic feet per day (bcf/d), billion cubic meters per day (bcm/d), or million metric tonnes per year. Given the prominent place natural gas occupies in the current news cycle, such unit heterogeneity does the public a disservice.

We’ve never been afraid to be the one in the audience to raise a hand and ask the clarifying question – the reward of understanding usually outweighs the risk of embarrassment – and we are the first to admit framing the European natural gas crisis to a consistent reference point is challenging. It is also essential if you want to grasp the magnitude of the issue and the viability of proposed solutions.

In this analysis, we’ll align the natural gas flows presented to a consistent measurement of billion cubic feet per day (bcf/d). Apologies to our non-US Doomers, but US supply will likely play a key role in weaning Europe off Russian supply, so we’re aligning to the unit you’ll likely see referenced regularly in the coming months.

Have a scratch pad nearby, but if we’ve done our job well you won’t need it.

The Gap & What Might Fill It

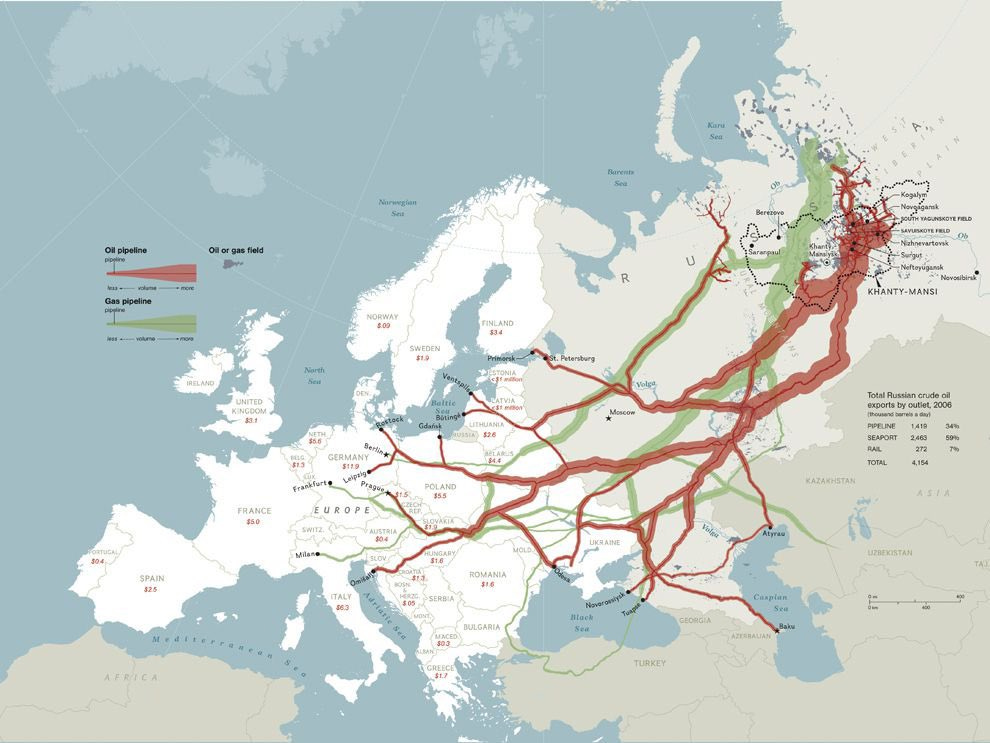

How much gas does Europe buy from Russia? Most estimates peg the annual amount to about 155 billion cubic meters. There are 35.3 cubic feet in a cubic meter, and there are 365 days in a year, thus Europe has a 15 bcf/d gap to fill by turning off the Russian spigot [(155 x 35.3)/365 = 15 bcf/d].

Thanks to the shale revolution, the US now produces approximately 96 bcf/d of natural gas. Of that amount, nearly 12 bcf/d is exported via newly constructed LNG terminals. Said another way, Europe’s Russian natural gas imports represent the equivalent of 125% of the entire current US LNG export capacity. This is a significant number.

Until recently, the US had six major LNG export facilities running at or above nameplate capacity. On March 1, 2022, Venture Global LNG's Calcasieu Pass facility in Louisiana shipped its first product, establishing a seventh hub. That project will continue to build out more trains, while Golden Pass, a 70:30 joint venture between QatarEnergy and ExxonMobil, is slated to come online in 2024. In all, these projects should add approximately 3.2 bcf/d of additional export capacity by 2025. There are several other projects at various stages of development, and assuming price differentials between the US and the rest of the world remain elevated, it is safe to assume these will eventually get built. Critically (and finally!), the industry is experiencing a newly warmed reception from the Biden administration:

“Industry executives in recent weeks described a shift in tone from policymakers as the White House scrambles to boost LNG shipments to European allies. Several U.S. LNG developers also pointed to an uptick in commercial talks over long-term contracts traditionally used to secure financing. The counterparties included European buyers that had shied away from deals for U.S. shale gas over climate concerns in recent years and buyers in Asia that face increased competition for supplies.”

While the US is a major global producer of LNG, it is hardly the lone player of size. Qatar and Australia produce similar quantities, and together the “big three” have more than half the global market share. Naturally, the soaring price of LNG is triggering a substantial global supply response. In addition to US growth plans, Qatar is making bold bets with plans to increase its LNG export capacity from approximately 11 bcf/d to 17 bcf/d in the coming years.

According to data from S&P Global, total LNG exports amounted to approximately 377 million metric tonnes in 2021. To convert this into our bcf/d framework, there are 48.7 billion cubic feet in a million metric tonnes and still 365 days in a year, making the global LNG export market approximately 50 bcf/d across all sources [(377 x 48.7)/365 = 50 bcf/d].

At a rate of 15 bcf/d, Europe relies on Russia for the equivalent of 30% of the entire global LNG export market. Given the price elasticity of demand for natural gas, and the fact that countries like Japan, South Korea, China, and India depend heavily on LNG imports to meet their energy needs, the nature of the challenge facing Europe becomes clearer.

The Access Issues Facing Alternative Supply

Aside from securing commercial agreements for alternative supply, there is also the issue of whether Europe has the capacity to accept more LNG imports. Regasification requires specialized import terminals and pipelines to distribute the gas, both of which seem to be in short supply. Here are two quotes from a Reuters story published prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine:

“This means most of Europe's LNG terminals are operating at full capacity, especially in north-west Europe, where they feed large economies Britain, France and Germany, raising the question of how much more LNG can be processed.

“Spain has the continent's biggest capacity, with six terminals, while Germany has none. The utilisation rate for the Spanish terminals was just 45% in January, data and analytics firm Kpler said.

‘The problem with Spain is that it has limited pipeline connections with the rest of Europe with only one pipeline that could take gas from Spain to France and so capacity is restricted somewhat,’ Laura Page, senior LNG analyst at Kpler said.”

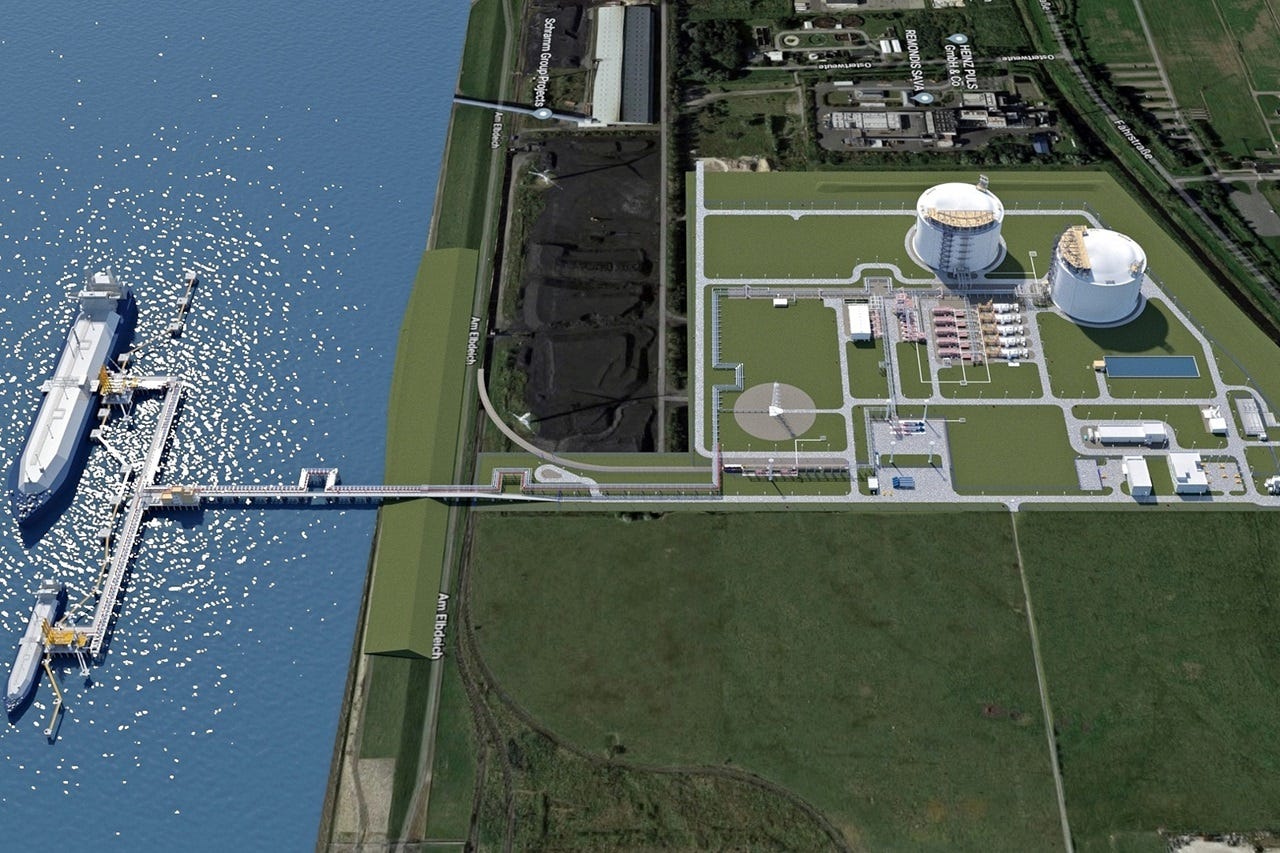

Germany recently announced its intention to build several new LNG import facilities, and three projects are progressing at an accelerated pace. A terminal in Brunsbuettel is slated to process 0.8 bcf/d, a project at Dow’s Stade site will handle 1.3 bcf/d, and a previously-shelved 1.0 bcf/d project in Wilhelmshaven has been resuscitated and accelerated. Although these projects will offset 20% of Europe’s reliance on Russian supply, they will not be operational until the 2025-2026 timeframe.

Irina Slav recently summarized the European Commission’s preliminary strategy in a three-part series of articles on her Substack, the first of which can be found here. The plan calls for an increase in LNG imports of 50 bcm per year, which approximates 5 bcf/d, or roughly one-third of the current amount supplied by Russia. Given enough time, the infrastructure needed to accomplish this objective can be built and the task is reasonable, but again, we’re talking years and not months here.

The plan also calls for the construction of more renewable energy projects, the burning of more coal and heavy fuel oil (although the EU’s dependence on Russia for these materials calls into question the wisdom and viability of this approach), developing of more biogas, and implementing a significant energy conservation drive. Here, the plan feels long on ambition and short on details, except for the whole “using less” part.

We close with something that is frustratingly absent from Europe’s current thinking (at least at the continent level): a nuclear energy renaissance. According to an admittedly ambitious plan from RePlanet called Switch Off Putin: Ukraine Energy Solidarity Plan, by simply arresting and reversing the nuclear phase-out underway in Germany, Sweden, and Belgium, Europe can offset 1.4 bcf/d of Russian gas (or approximately 10% of the gap). Further, by implementing emergency funding to substantially improve the performance of France’s existing nuclear fleet, another 2.5 bcf/d can be offset (approximately 17% of the gap). Although France and the UK have recently announced major nuclear power expansion plans, Germany is still resisting, and its final three nuclear power plants are scheduled for permanent closure by the end of this year. One wonders how much pain Germans will have to suffer before this nonsensical policy stance is reversed. We suspect we won’t have to wait long to find out.

Alas, putting these components into consistent terms is like turning the focus on a microscope. Once you get it right, the nature of the subject is revealed. Global natural gas flows are a complicated business but some simple themes from this exercise demand recognition: global export capacity is at full throttle, meaningful additional capacity won’t come online for another 2-3 years, and Europe’s import capacity is equally tight.

Europe’s plans may alleviate some of the shortfall, but the continent needs to face the reality of belt-tightening on the demand side. Barring that, go nuclear!

If you enjoyed this piece, please hit the “Like” button and consider upgrading to a paid subscription to continue receiving our articles after April 30th!

Another excellent piece putting facts out there. As an ex employee of 42 years with one of the worlds biggest energy (Oil and Gas) companies I am only too well aware of long it takes to build the supply infrastructure for energy. I am also very well aware of the risks associated with hydrocarbon exploration and production. A company can spend billions hunting for oil and gas in a promising new zone only to find its wells come in "dry". That company can also spend billions developing an oil and gas field only to find the wells produce a fraction of that originally estimated or if located abroad, can find a government wanting to change the terms and conditions impacting the original profit expectations significantly. Those aforesaid negatives are of course outweighed by the fact that when done well, production can produce large revenues and when oil rises in value (usually unexpectedly) bumper profits. Unfortunately the latter sometime cause the host governments to increase their offtake tax takes and sometimes impose windfall profits taxes. All of the aforementioned have happened throughout history and also to the company I worked for.

What is NEW today, is the dominant green agenda and the vilification of the business providing the worlds energy supply. The drive to get oil and gas companies to develop solar and wind is foolish. It is the lack of oil and gas that is going to bring our western civilization low. Oil (and gas) are the BLOOD of our industrial post WW2 world and SHALL remain so for decades. What is going to happen today though, is that people and governments have forgotten the criticality of energy security. What Europe in general and Germany in particular is about to find out, is they have traded away their energy security and placed it into the hands of an "enemy". The real impact on Germany has not yet been seen. Just wait till the reality actually sets in.

Three final comments:

1. CO2 emissions are going to soar in the next few years, I look forward to the increasing panic by the COP signatories as they witness their turn to solar and wind does not produce energy security, indeed it produces the opposite!

2. The green "anti nuclear" faction have pointed a Benelli semi automatic at both their feet. Modern nuclear is the ONLY ANSWER folks. I suggest you start shouting about this loudly now and even then it will take a decade to really make a big difference!

3. Finally, and I know this will generate some negative responses, I STRONGLY suggest to you that Putin is fully aware of all of this. Our media is currently full of Ukraine fear mongering and Putin vilification (much like 2020/21 were full of Covid fear mongering). What Putin has done in Ukraine to civilians is just terrible in the 21st century, but humans haven't really changed for millennia and so this won't be the last time we see very bad behaved humans wreaking havoc on the neighbors. However, Russias position as a major energy, materials and agricultural exporter means it is no Afghanistan, Libya, Syria or Iraq. As we can also see things don't seem to be going quite the way the EU thought (or the US perhaps) with sanctions.

While principle demands the economic pressure is maintained on Russia hoping they will end the war sooner rather than later, common pragmatic sense dictates the West tell Ukraine to work with Russia to end the conflict soonest and if that means holding referenda in the eastern provinces to see if they want to be part of Russia or independent or not, so be it.

My apologies at the length of this response but at my age and with a reasonably strong geopolitical / historical "bent (and library) I have earned the right to be very suspicious of ANY narrative put of there by elected officials or their bureaucrats. I firmly believe the "Long Emergency" that started in 2009 is well underway and has yet to peak. Get ready to see economic and political chaos in the Western democracies.

Great Doomberg analysis.

What additionally needs to be factored in is the cost differentials between ‘shipping’ ‘Gas’ via LNG carriers and ‘delivering’ gas via pipeline. Gas being exported via LNG tanker needs to be ‘liquefied’ (costs $1-$1.30 per 1000 cubic feet); then shipped on an LNG carrier (and charter rates can go through the roof-they’ve ranged recently from $150k a day to $350k(!) a day- and US Gulf to Europe time is circa 18 days); then the LNG needs to be ‘re-gasified’ at a cost of between 0.35-0.50 cents per 1000 cubic feet.

So the gas price arbitrage has to be ‘attractive’ enough to make the switch from the US (& Asia) to Europe (which may have the effect of keeping EU gas prices high!).

The economic impact on European industry and citizens will be massive-& will severely impact any chance of a European recovery. Factor in on top of that that fossil fuel prices (coal, oil and gas) are ‘elevated’ and likely to go significantly higher-which in turn feeds into the cost of ‘manufacturing’ the required European LNG facilities- and also critically ‘Renewables’-which consume gargantuan quantities of ‘natural resources’ in their manufacture & render them even more economically unviable and capital destructive.

(And just think of all the CO2 that is going to be emitted in all of the above processes!)

Energy ‘IS’ GDP.

What matters is ‘EROEI’- ‘Energy Return On Energy Invested’ which are approximately-Nuclear 1:100; Hydro 1:36; Coal & Gas 1:30; Wind & Solar 1:4 - and one can appreciate a growing ‘problem’.

Throw into the mix the levels of European sovereign debt; the Target 2 balances of €1.6 trillion (approx) (GDR on the hook for €1.150 trillion!) and the ECB’s ‘balance sheet which is approaching €9 trillion-none of which is sustainable without massive QE-which will drive inflation and increase the costs of fossil fuels- so potentially setting off a vicious upward commodity price spiral possibility in what should be a ‘rising interest rate’ environment.

Even a basic analysis shows just how ruinous a multi decade long misguided mismanaged ‘energy policy’ has been.

Just where have all the political & economic ‘strategic planning genuises’ been over the last three decades? Pursuing ‘Net Zero’ and ‘ESG’ programs?

What could possibly go wrong?